Ye Olde Basal Rate: Its Effect on T1D Management and Long Term Complications

Basal insulins and basal rates are a double-edged sword for T1Ds

Pop quiz: Do you experience any of these

Big differences in glucose levels between bedtime and morning—or, before and after meals

Occurrences of hypoglycemia (aware or unaware),

High glycemic variability.

Seems like all T1Ds experience these, right?

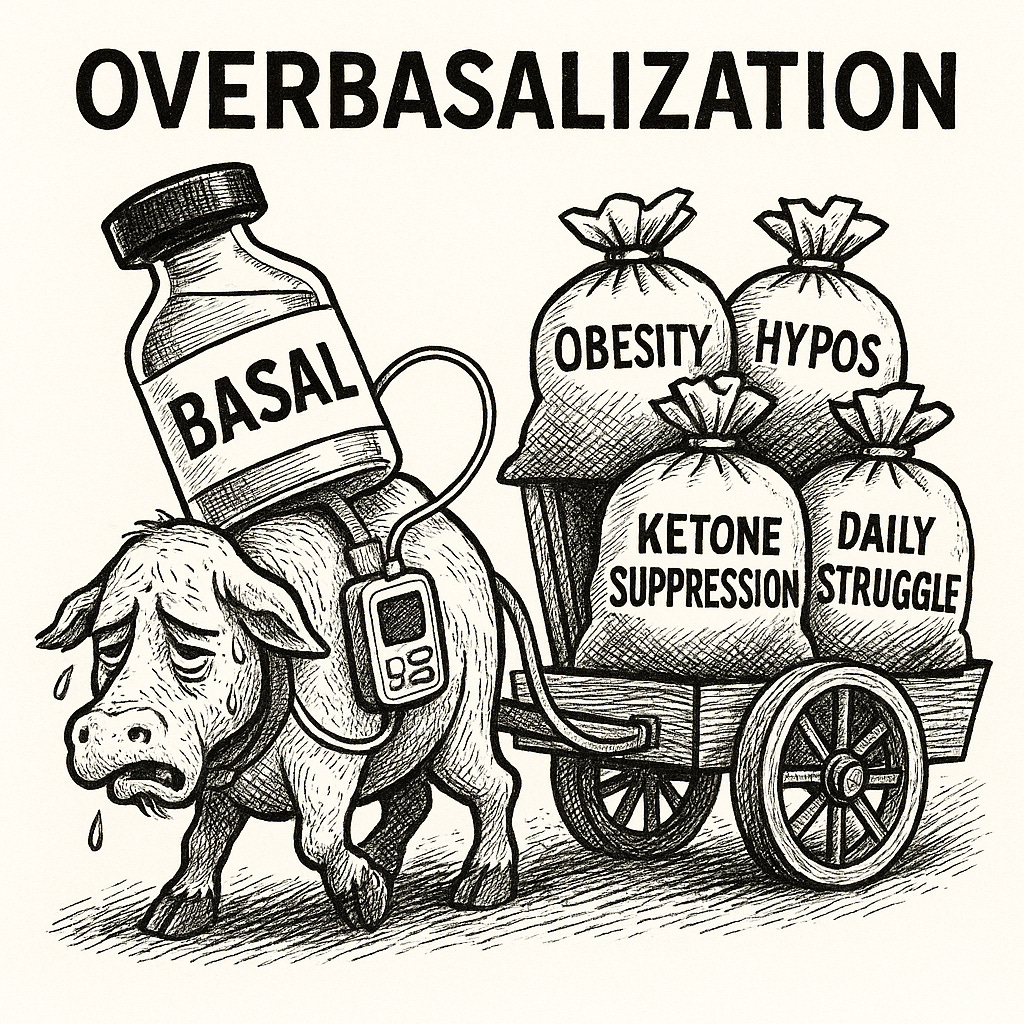

Exactly. These are the criteria that the ADA has identified as signs that your background (basal) dose is too high, otherwise known as overbasalization. This is according to section 9.27 of the ADA’s 2025 guidelines, which now recognize overbasalization as a major health concern for T1Ds.

And yet, this quiet, subtle, yet powerful change in the ADA guidelines hardly garnered a whisper in the T1D community, despite the enormous harm that overbasalization have been reaping for decades—harms that have been published in ADA journals and other highly reputable medical literature.

Consider this 2023 article in Lancet titled, Obesity in people living with type 1 diabetes, showing that the rate of obesity reached 37% in 2023 compared to only 3.4% in 1986. The authors pointed to excess basal dosing, noting:

“Insulin profiles of automated systems do not match basal and mealtime insulin needs,” and “defensive snacking to avoid or treat hypoglycemia.”

More citations will follow later.

But the harms go well beyond obesity. Excess basal insulin is responsible for these problems as well:

Everyday glucose management becomes harder. Too much basal means you have more insulin onboard than you’re aware of, making bolus math less accurate and glycemic swings more likely.

Hypoglycemia increases. High basal doses make surprise lows inevitable, forcing unwanted carb intake.

Fat storage accelerates. Insulin drives fat creation, so excess basal fuels weight gain (obesity), which leads to metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance, similar to T2D—the dreaded “double diabetes”.

Exercise becomes harder—or avoided altogether. Physical activity pulls glucose from the bloodstream independent of insulin. With excess basal, hypos hit fast, not only terminating exercise too soon, but fuels fear of exercise. In fact, fear of hypoglycemia (FOH) is the leading reason why most T1Ds don’t exercise, according to the literature review paper, Fear of hypoglycemia, a game changer during physical activity in T1DM. And this is the most devastating of all, because exercise is one of the most important ways to improve metabolic health, lose weight, improve insulin sensitivity, and ease the burden of glycemic control.

Cardiovascular risk rises. Excess insulin itself is atherogenic, compounding and accelerating the damage already wrecked from high glucose levels. ASCVD remains the leading cause of death for T1Ds, cutting lifespan by 12–15 years. (For more on this, see my article, Insulin and Heart Disease: What You Should Know.)

Ye Olde Basal, virtually long forgotten from days of yore, has a HUGE effect on both short- and long-term health outcomes and daily self-management.

So, why is the ADA acknowledging overbasalization only now—and so quietly? Even more curious, why offer no real guidance on what basal dosing should be?

That’s what we’re here to examine more closely. This article is the first in a four-part series on overbasalization:

This article: How chronic overbasalization harms long-term health, and how ADA’s basal standards evolved from simplicity, lower A1c targets, and fear of DKA.

Next: DKA and why the fear is unjustified. In my article, Ketones: The Unjustly Demonized Villain in T1D Management, we explore how ketones actually support metabolic health, and why DKA is not the monster hiding under the bed.

Then: The chaotic reality of true basal needs is covered in my third article, Basal Dosing: How Much Do We Need?, which gets into more detail on how much insulin we actually need—and when.

Finally: Basal Insulin Reduction: A How-To Guide using “Active Learning” covers practical strategies to dose more efficiently for weight loss, fewer hypos, much easier daily T1D management, and healthier outcomes.

As always, we’ll lean on high-quality, peer-reviewed evidence—not dogma.

Long-term Health Consequences of Improper Basal Dosing

Excess insulin levels—also called hyperinsulinemia—is the death knell for all humans, and diabetics of all types suffer from it. This condition is what defines type 2 diabetes (T2D): As the pancreas struggles to produce increasingly more insulin to keep up with high caloric consumption, it creates increasingly more fat. Eventually, beta cells can’t keep up, which is when glucose levels start to rise. Only then is the person diagnosed with T2D, despite the fact that the disease had set in decades earlier.

Exactly the same problem exists for T1Ds, except that they don’t rely on their beta cells for that excess insulin, they inject it. And much of it is in the form of excess basal dosing. As T1Ds administer increasingly larger amounts of insulin in their efforts to chase down A1c levels, they gain excess weight and develop the same metabolic dysfunctions as T2Ds, a phenomenon called “double diabetes”.

The Lancet paper that showed the rapid increase of T1D obesity is hardly the first to call it out. A 2024 Medicina article compiled hundreds of papers showing the same thing in the literature review, Interventions Targeting Insulin Resistance in Patients with Type 1 Diabetes: A Narrative Review. Here, the authors echoed the Lancet’s explanation: “insulin profiles do not match basal and mealtime insulin needs,” leading to defensive snacking, and hence, weight gain.

A 2017 meta-analysis of decades of papers was published in the journal Endocrine Reviews (2018) titled, Obesity in Type 1 Diabetes: Pathophysiology, Clinical Impact, and Mechanisms. Once again, the authors further underscore the connection, tracing weight gain to “intensive insulin strategies, wherein basal and mealtime dosing often mismatch biological needs and drive hyperinsulinemia.”

The list goes on and on.

It’s not just obesity. Excess amounts of insulin also contributes to atherosclerosis (damage to the arteries) and cardiovascular disease, the combination of which is ASCVD. Surprisingly, this has been known as early as two years after insulin itself was discovered in 1929, according to the literature review article, Insulin Resistance and Atherosclerosis: Common Roots for Two Common Diseases? Cardiologist Paul Dudley White noted in 1931 that “diabetes favors arteriosclerosis” and that an “excess of insulin” might contribute to this condition. (You can read more about this in my article, Insulin and Heart Disease: What You Should Know.)

The ADA is keenly aware of these problems, as many of these studies have been published in ADA journals. The recent changes show their acknowledgement of the problem, and yet, guidance on what to do about it remains vague. To understand why, we look to history.

The Unchanged Foundation: How 1970s Guidelines Became Today's "Aggressive" Recommendations

In the 1970s, long before it was possible to test for blood glucose levels at home, or even to test for long-term glycemic management (such as the HbA1c test), self-management of T1D was pretty blunt: Take one dose of long-acting (basal) insulin in the morning (such as Lente or UltraLente and later, NPH), and two SMALL doses of Regular insulin: One for breakfast and one for dinner.

All other meals or snacking was taken care of by the basal insulin.

In this model, you “ate to the insulin”, meaning that you ate when you went hypo, or felt it coming on. You’d quickly see your own, personalized daily pattern. When that time of day comes that you’d “feel” your blood sugar drop, you’d eat. In short order, you’d plan your daily feeding times around that.

It wasn’t good by any means. No one claimed it was “healthy”, which is when low-carb diets were promoted most aggressively.

However, it was incredibly easy. When I was growing up in the 70s, never did I or anyone I know complain about how complicated T1D was. It wasn’t a struggle. I never even took insulin to school with me. I’d just know to eat at 12pm (for me), cuz if I didn’t, BOOM.

T1D was both easy, and incredibly unhealthy—but we didn’t really know it, or at least, know why. Odd as it may sound, there was debate as to whether long-term complications were due to excess glucose levels, or just an unavoidable byproduct of the genetics of this unique autoimmune disease.

At the time, the ADA guidelines for basal dosing was around .5u for every kilogram of body weight. “Set it and forget it.” The small bolus doses for breakfast and dinner was to help support times when the basal was less active (coming onboard or tapering off).

By the 1980s, the first consumer grade blood glucose meters were made available for home use, so the thinking was that patients could actually make better decisions about their management. As it happened, the HbA1c test had also become standardized, so it was also possible to track patients’ glycemic control over time.

This presented researchers with a big opportunity to challenge that big question about long-term complications: Were they really just genetic, or can we track complications with long-term glucose levels. This brought the landmark Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT, 1983-1993). And indeed, it changed everything about T1D management.

In the study group, instead of the typical protocol of the two, small Regular injections for meals, study subjects took three doses, and each one was much larger. The control group were those (like me) that just took big, basal doses and small regular doses at morning and night.

The results were clear: microvascular complications were dramatically reduced among the study group. Lower long-term glucose levels reduced retinopathy, kidney disease and others.

That very concept of being more aggressive with bolusing for meals was the game changer, validating intensive insulin therapy.

The question before the ADA was whether to change the guidelines for background insulin. And if so, to what?

As it happened, Kenneth Polonsky and colleagues published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1988 titled, Abnormal Patterns of Insulin Secretion in Non-Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus. The authors measured 24-hour insulin secretion patterns in fourteen T2D volunteers, “to determine whether non-insulin-dependent diabetes is associated with specific alterations in the pattern of insulin secretion.”

Their key finding was that “basal insulin secretion represented 50 ± 2.1% of total 24-h insulin production”.

That’s what established the 50/50 protocol for basal dosing, and it’s been that way ever since.

Unfortunately, the researchers didn’t scrutinize the Polonsky study very well. It’s fundamental flaw wasn't just its tiny sample size of only fourteen T2D subjects—it was the assumption that insulin secretion patterns in people with insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia would somehow inform the insulin requirements of people with T1D who have no endogenous insulin production at all.

Despite these fundamental differences between T2D and T1D physiology, this became the foundation for T1D basal guidelines adopted by the ADA: 50% of your total intake of insulin should come from basal dosing, also known as the 50/50 rule. (Note that we will explore this study in detail in the article, “The Physiology of Background Insulin.”)

Put the two together—aggressive meal bolusing and the 50/50 rule—and you get a hybrid system that initially seemed to work. Higher basal doses made T1D management ‘easier’ because few interventions were required. If you miss meal boluses, or were simply inaccurate, basal was a safety net. At the same time, aggressive bolusing yielded lower A1c values and a reduction of microvascular complications.

This was hailed as a win for T1Ds!

Alas, it turns out that this model had a lot of downsides, and it took decades to figure it out. In the 2014 article in Diabetes Care, The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Study at 30 Years: Overview, the authors found that, while those who were under tighter control didn’t suffer microvascular damage as much, there was a huge increase of macrovascular damage, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), leading to heart attacks and strokes, among other comorbidities. The combination of high basal rates and aggressive meal bolusing yielded a net addition to total insulin intake that led to today’s obesity problems (and the other listed complications).

Also, daily insulin management got more increasingly more complicated. Struggling with weight gain plus complex dosing calculations for meals created a perfect storm for ill health—physical and mental.

But wait, there’s one more factor to consider: Diabetic Ketoacidosis, or DKA, a nightmare that’s etched in the minds of all T1Ds. Higher basal dosing is seen as a safety net to protect against DKA.

But is it?

Basal dosing and DKA: What’s the risk?

Since the DCCT was such a landmark trial that changed how the disease was managed, you’d think that the risk of DKA would be better understood.

According to the article, The Effect of Intensive Treatment of Diabetes on the Development and Progression of Long-Term Complications in Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus, the DCCT reported DKA incidence of approximately 1.8–2.0 episodes per 100 patient-years, but the rate of DKA incidents was nearly identical in both intensive and conventional treatment groups.

In other words, more aggressive insulin regimens did not lead to a lower risk of DKA in the DCCT. But the fear persisted. And given that higher basal dosing continued to keep daily management “easier” (but not healthier), basal dosing continued to increase since the 2010s, all while DKA rates have always remained low and stable.

When insulin pumps became more common, these higher basal rates just migrated over.

But the fear of DKA is simply unfounded, and an innocent bystander is ketones. These are produced when you burn fat for energy, which you need to do in order to lose weight or exercise. Ketones are also a valuable energy source—an alternative to glucose in some conditions.

And yet, ketones are mistakenly seen as a sign that you don’t have enough insulin onboard, even when you actually do. This partially explains why many feel they need higher basal rates: As a safety precaution to protect against DKA. Needless to say, this myth has persisted far too long. I get into this in greater detail in my article, Ketones: The Unjustly Demonized Villain in T1D Management.

Fear of DKA, along with rising obesity, brings us full circle to 2025 and the ADA’s revised Recommendation 9.27 cited at the top of this article. Overbasalization is finally getting attention. But the solution? Not that simple.

The ADA is faced with a far more complicated problem than just high basal rates because the latest science reveals that “basal needs” are not constant, reliable, or consistent. There is no “rate”. Someone’s physiological need for “background” insulin—the dosing needed for metabolic needs unrelated to food consumption—is not calculable. It can’t be measured. There’s no formula. All that makes it hard to translate into brief, actionable targets or plans that overworked medical care teams can explain to patients.

In fact, “overbasalization” isn’t even easy to say!

The ADA’s lack of specificity on exactly how to reduce those high basal rates is (probably) why the new guidelines have been so quiet.

For self-motivated, engaged T1Ds, there are ways to address this. And that’s what this series is all about. So, I hope you read the articles that follow.

Summary

As a general rule, ADA basal guidelines aim to solve a critical need in the population: Giving overworked healthcare providers and patients alike very simple, easy, concise formulas for insulin therapy to provide a safety net for the most unhealthy segment of the population.

But these guidelines don’t apply to everyone else—the segment of the population that can be more proactive about their self management and is willing and capable of engaging in hands-on management techniques.

Reducing basal rates isn't just possible, it's transformative and far simpler once the paradigm is understood. Many have successfully reduced their basal to near-zero, both MDI and pump users alike, achieving weight loss, fewer hypos, easier daily management, and genuinely healthy outcomes.

The key is understanding that this isn't an all-or-nothing proposition. There's a spectrum of approaches, including the likelihood that your basal rates can be just modestly tweaked.

The primary barrier for achieving this is psychology—it’s extremely frightening to modify a dosing protocol you’ve known your whole life. It would be even harder if you did it blindly, without understanding the underlying physiology of what your body actually needs. And then again, there’s a fear of DKA, a horror story so ingrained in us that dispensing with that is essential.

This is why the next article in the series, Ketones: The Unjustly Demonized Villain in T1D Management, is specifically about DKA, what it is—and isn’t—and how the fear of it is entirely unjustified.

That will lead us into the third article, Basal Dosing: How Much Do We Need?, gets into more detail on how much insulin we actually need—and when.

Finally, my last article Basal Insulin Reduction: A How-To Guide using “Active Learning”, explores ways to improve basal insulin profiles safely and effectively, while maintaining the tight glucose control that actually matters for long-term health.

Fantastic, eye-opening article - as always! I cannot wait for the next installment because I am ever vigilant and while my daily std. deviations are low and my A1C is great, I know I could be over-basaling. I cannot wait to learn more. Thanks, as always, for wonderfully written articles based on credible sources and all the leg-work you do for us to get these nice digestible guidelines for our Diabetic journeys. I study my clarity data every morning and write out specifics of overnight BG’s determining what happened when only Tresiba was working to determine the dose for that day. It will be interesting to see how I could use boluses differently. I don’t know how much wiggle room I have given my fairly boring regular meals and no snack lifestyle, but being on MDI is a blessing in general and specifically for what you are showing us here. Thanks again!

Dan, another outstanding article. You are spot on regarding your assessment of endocrinologists & PCP’s. I am feeling a bit old, as I was in my IM residency when the DCCT study started! Agree that easiest & best insulin dosing are not one and the same. Keep up the great work that you are doing!

Best, David LaHue