Basal Dosing: How Much Do We Need?

The physiology of “background” insulin is complex. Dosing is another story.

This article is part 3 of 4 in a series that covers overbasalization, a phenomenon that the American Diabetes Association has identified in section 9.27 of their latest (2025) guidelines as being a major health concern for T1Ds.

I covered the background for this new guideline in the first article of this series, Ye Olde Basal Rate: Its Effect on T1D Management and Long Term Complications, summarizing that overbasalization can lead to severe and frequent bouts of hypoglycemia and a rise in obesity.

The root of the problem is the 50/50 rule. Established in the 1980s, it states that 50% of one’s total daily dose (TDD) should be in the form of basal dosing. And yet, the ensuing decades found that this ratio led to the health concerns the ADA is worried about.

What the guidelines didn’t do, exactly, is indicate new ratios. The tenuous nature of their latest document suggests the topic more complicated than what meets the eye. Indeed, it’s not that simple. In short, it all comes down to your poor, dysregulated alpha cells. Yes, alpha cells. They signal the liver to produce glucose, but they get a good deal of signaling from your beta cells, which don’t work, so alpha cell signaling is causing your liver to be wildly inaccurate how much glucose to produce. And that is the glucose your “background” insulin is supposed to cover. It’s the wild west inside your pancreas.

To get to the bottom of this, which will help in basal dosing strategies, we need to understand this funky glucose production from your liver that’s throwing everything off.

Background Metabolic Activity

When you eat, your body utilizes that food to extract (or make) glucose. But when you don’t eat, or glucose levels fall too low, counter-regulatory hormones (primarily glucagon) signal the liver to produce new glucose to keep that fuel supply line going. The effect is called hepatic glucose autoregulation. (“Hepatic”, meaning “liver”.)

“Autoregulation” is key here. It’s what the liver does “automatically” when the body needs glucose that isn’t provided by food. It’s the background activity that basal insulin is intended to cover. Where things went awry when they came up with the 50/50 guideline is the assumption that the liver is always producing glucose at a steady rate.

Turns out, it’s not a steady state of production.

The physiology of hepatic glucose production

This was formally demonstrated by Rizza et al. who published their findings in The New England Journal of Medicine, in an article titled, Control of blood sugar in insulin-dependent diabetes: comparison of an artificial endocrine pancreas, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion, and intensified conventional insulin therapy.

The researchers connected T1D subjects to two IV infusion sets: one for insulin and the other for glucose, a process that is now known as an glycemic clamp. By delivering both insulin and glucose at constant rates and monitoring blood glucose levels, they were able to “clamp” glucose levels at whatever number they wanted by turning whichever knob they wanted. By keeping both levels steady, they found a direct causality between the infused insulin and glucose levels. Had the liver been producing any glucose at all, it would show up in the constant blood glucose monitoring and thereby require more insulin than the balanced levels being administered.

Hepatic glucose production is non-existent when both plasma glucose and insulin concentrations are adequate.

So, theoretically, if you were to just eat all day, or at least, keep your blood glucose levels elevated, then your liver will never produce a drop of glucose due to “autoregulation”, and you wouldn’t need any basal insulin. In other words, your basal ratio would be zero. You’d be surviving solely on bolus dosing for your food.

On the other end of the extreme, what if you didn’t eat anything at all (fasting)?

Fasting: Basal ratio is 100%. But not basal rate.

If you fast, your cells would need glucose, triggering counter-regulatory hormones (glucagon) to tell your liver to produce it. Here, your basal ratio would be 100%. But the critical point that you need to etch into your brain:

Basal RATIO is not the same as Basal RATE.

The clearest demonstrates of this can be found in the ZeroFive100 Project, where eight people—two T1Ds and six non-T1Ds—walked 100 miles in five days, consuming no food—zero calories. Both T1Ds required insulin, of course, and technically, this is entirely basal dosing because there is no food-bolusing to consider. One T1D took a basal insulin, but the other did not—he bolused “as needed”, and found that his glycemic control as tighter, meaning that it more closely resembled actual hepatic glucose production. Similarly, he found there were periods where the liver produced no glucose, thereby requiring no insulin. This insulin-free gap is not just physiologically normal, but it weighs heavily into how basal profiles should be administered.

We can reduce these lessons into the three key RULES that will affect everything you need to understand about basal dosing:

Basal “needs” are not flat at all. So, even if the ratio of basal insulin is 100%, it is not covered by a flat basal insulin formula or algorithmic “rate” for pump users. Again, this will show up in many studies, including those with more traditional diets.

The “bolus as needed” method is a legitimate and effective way to administer insulin to cover background metabolic needs. Although the conditions presented in this experiment are extreme, it demonstrates the concept, and more studies like this utilize this “zero-basal/as-needed bolusing” method to cover what would otherwise be covered by “basal” insulin. It’s just delivered in a more precise manner.

One T1D went hours overnight with no insulin at all demonstrates a case study of a well-known physiological phenomenon: There can be insulin-free gaps in T1D management. Accordingly, if there were insulin onboard during these physiological windows, it would trigger hypoglycemia. This is one reason why the bolus-as-needed method is more effective than a flat basal insulin or basal rate.

Other, more clinical studies further validate the phenomenon that basal rates are not “flat”. One study was described in the 2005 paper, Characteristics of basal insulin requirements by age and gender in Type-1 diabetes patients using insulin pump therapy. Here, the authors wrote that basal needs ended up being “pulsatile, with 3–6 minute oscillations—meaning basal needs aren’t flat at all but continuously fluctuating at short timescales.”

More recently, the 2022 arXiv paper, Temporal patterns in insulin needs for Type 1 diabetes, analyzed hundreds of millions of hours from T1Ds’ pumps from OpenAPS data and found complex temporal patterns in insulin need, driven by carbs and less obvious factors—suggesting static basal profiles are too simplistic.

This pulsatile pattern of insulin needs would validate the “bolus on demand” approach, as opposed to the “flat basal inulin” approach that is currently used by most T1Ds.

With this background, and these three rules, we can now move forward towards more real-world situations where people actually eat.

How liver-produced glucose is affected by food

We start with what we know about the two extremes. On the one end, fasting requires insulin to cover background activity, which is 100% basal. On the other extreme, the Rizza experiment demonstrated that if we were to eat all the time, the liver would produce no glucose at all, so that profile would be 0% basal.

By introducing food, there’s now a mix of bolus and basal dosing “needs”. (You’ll see why I put that in quotes soon.)

As you already know, it depends on what you eat. Fast-absorbing carbs need more immediate bolus insulin dosing (Rizza), whereas fats and protein absorb more slowly, stimulating liver glucose production, so there’s a lag as to when insulin would be needed, which would be considered basal.

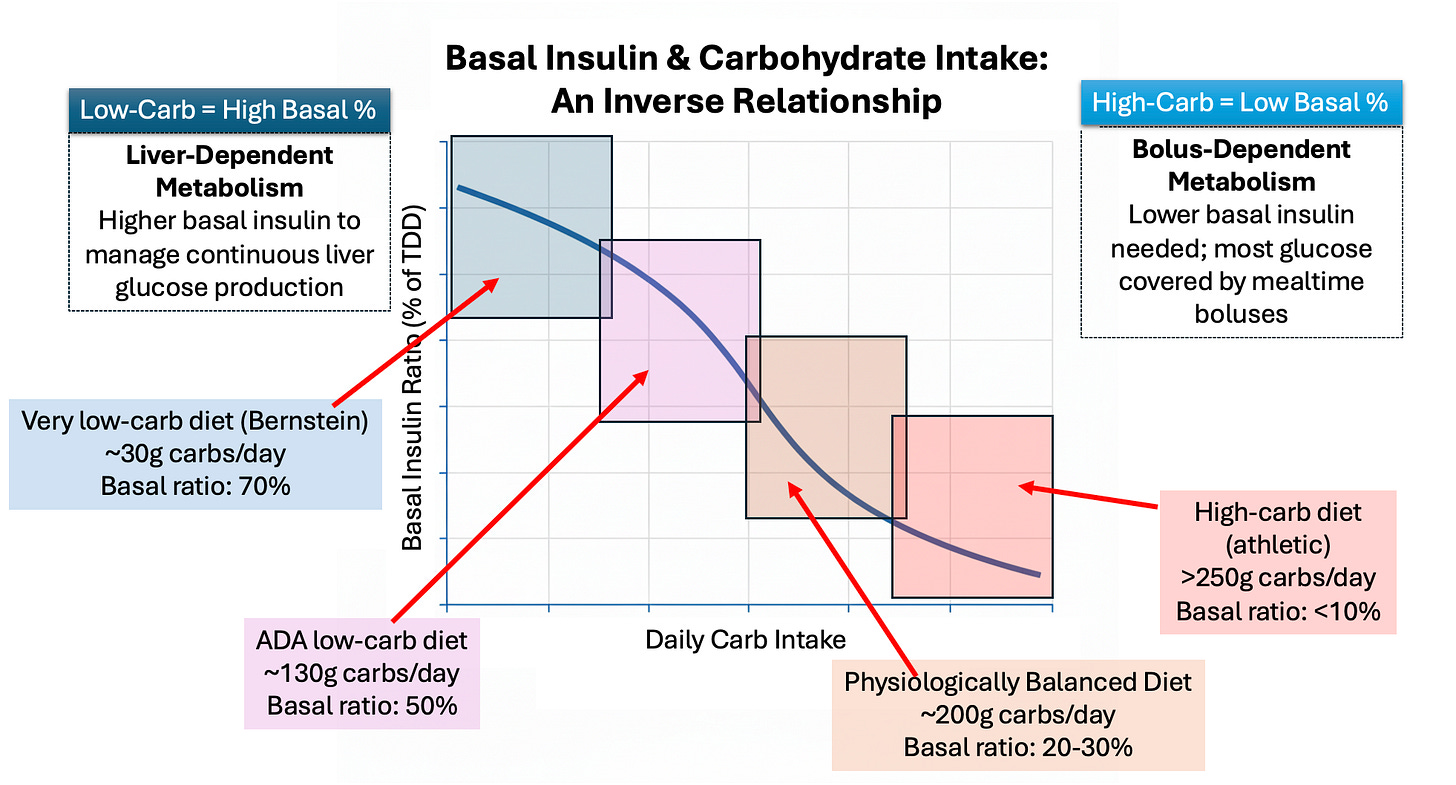

This is effectively controlling how much glucose your liver produces. The more carbs you eat, it’s more like the glycemic clamp, where your liver produces no glucose. The less carbs you eat, your liver produces more. Hence, basal ratios will be inversely proportional to your carb intake. This chart illustrates the point:

This chart illustrates estimated basal ratios based on carb assumptions, but keep in mind the three rules: The liver glucose production is volatile (not flat), so basal ratios are not the same as basal rates.

Low-Carb Diets

The lowest-carb diets (i.e., Bernstein) calls for such low carbs that most of one’s insulin needs are covered by basal insulin. At only 30g of carbs/day, this is a state that the liver perceives as similar to starvation, where it needs to produce nearly all the glucose the body will use. As noted earlier, basal insulin will cover most of it.

For this diet, a typical basal ratio is closer to 70/30, but because the basal ratio is not the same as basal rate, the 30% of insulin that comes in the form of bolusing is, more likely than not, really just covering the volatility of the liver’s glucose production. In other words, the effective basal ratio is likely closer to 90/10.

Note that it takes time for the body to become keto-adapted, shifting it enzymatic activity to favor making glucose from substrates like amino acids, fats and proteins. Indeed, for those who can do it, they often achieve A1c levels in the 5-6% range, with very little daily volatility.

But there are costs that come with this, primarily metabolic and cardiovascular disease. The longevity stats on this group are pretty low, save for a small percent whose genetic dispositions are uniquely capable of handling it. All the stats and a full analysis is provided in my article, The Paradox of Low-Carb Diets: A1c vs. Metabolic Health.

ADA “low-carb” diets

Moving up the carb spectrum is the ADA’s definition of a low carb diet—130g/day. Here, your carb intake is higher, which starts to shift your insulin needs away from basal and towards mealtime boluses.

You’ll also notice 50% basal ratio. On its face, that looks like it explains the ADA’s 50/50 basal recommendation. Ironically, that alignment is purely coincidental. The ADA never specifically ties these together, nor are they discussed at the same time. The 50/50 recommendation is provided irrespective of diets, though it happens to also recommend its low-carb diets for those who are overweight.

It’s also critical to point out—AGAIN—that basal ratios are not the same as basal rates. In the real world, even if you were to adopt the ADA low-carb diet, the mix of glucose from carbs and glucose from the liver is such that your bolus dosing for meals is covering a huge percentage of what might otherwise be considered “basal”, simply because that’s how insulin in absorbed in the body. This is similar to how the bolus dosing in the Bernstein diet was more likely covering basal needs; the volatility of the liver’s glucose production just required some bolusing to cover those excursions.

Let’s use an example of a peanut butter sandwich, where the bread represents 40g of carbs, and the peanut butter is 5g carbs and 20g fat+protein. Whatever you bolus for that (which varies among individuals), most people’s calculation will cover that whole meal, thereby covering the basal portion of it.

Now, “most people” in this respect is a very wide range, and that’s what makes all this complex. How you actually balance that is entirely based on your own, personal, unique physiology. We get into strategies on that in the next article.

The point for now is that people don’t think about the basal insulin they’re taking when they calculate bolus dosing for meals. They think of the two as entirely separate, and that’s what’s gotten us into this problem of overbasalization. They think that “basal” is entirely separate, but it’s not. Basal dosing is covering meals, and most T1Ds don’t know it.

And this is precisely why the current 50/50 guidelines are affecting bolus dosing in ways that they shouldn’t.

Therefore, it needs to be emphasized that the ratios illustrated in the graphic do not necessarily imply that you need to split your actual basal and bolus dosing along those percentages. Rule #2: On-demand dosing reconciles this problem by separating basal and bolus dosing calculations.

If you dose as needed, when needed, you’d remove the distinction between basal and bolus entirely, and achieve a better TIR. Again, this is covered in the next article on demand-driven dosing.

Higher-carb diets

As we move up the carb-intake spectrum, we get to where most Americans are, and of course, this is not necessarily good. Higher-carb diets demand a great deal more insulin, and if we’re going to limit this to glycemic control and no other health factors, then most of those meals (carbs + fats + protein) are going to be covered by bolus dosing. It’s the peanut butter sandwich example on steroids.

Under these conditions, which is most Americans, the liver will rarely enter a state of autoregulation during the day, thereby minimizing its own glucose production, minimizing the need for basal insulin.

Night is a separate problems, and we’ll get to that later.

Before we leave this section it should be said that high-carb is not always unhealthy. In fact, the ideal diets is one where fuel intake should meet energy demands. In other words, exercise. The more you exercise, the more energy you consume, so the more fuel you need to take in, which has a huge effect on glucose and insulin metabolization, thereby affecting both bolus and basal dosing management.

Exercise and Dosing

One of the main drivers for health among all humans, T1Ds or not, is exercise. It is the sole method to improve cardiovascular and metabolic health, both of which are the primary drivers of longevity. And exercise requires carbohydrates. It’s true that lower-carb (even keto-adapted) individuals can exercise if they’ve trained their systems intensively, but there’s a cap on the level of exercise they can achieve without direct access to larger quantities of glucose in the bloodstream. The liver just can’t produce it in high enough quantity on demand for higher intensity exercise, which is essential for long-term metabolic health. Again, see the article on low-carb diets for details.

Because people’s exercise levels also vary a lot (including none at all), a healthy diet (insofar as carbs are concerned), should based on your weight and physical activity levels. (A table describing various dietary guidelines for physical activity is in the article on low-carb diets.)

This leads us to the primary lesson to be derived here:

Assuming your diet has the right balance of carbohydrates for weight and exercise levels, all meals and snacks provide sufficient glucose such that the liver rarely ever enters autoregulation mode. Hence, basal requirements drop to very low levels.

The reason exercise is so critical in this context is that it amplifies a particular part of our physiology that we haven’t yet discussed: Glucose absorption that does not involve insulin.

Obligatory tissues, such as the brain, much of the splanchnic bed (stomach) and skeletal muscle, account for a large share of glucose absorption independent of insulin—a process called, non–insulin-mediated glucose uptake, or NIMGU. The brain consumes 130g of glucose per day without insulin, for example.

There mere contraction of muscles also take up glucose without insulin, but the level is insignificant unless you engage in a certain minimum threshold of activity. Walking does more than you think, allowing you to reduce insulin dosing for meals if you were to walk for 15-20 minutes afterwards.

As exertion levels rise, muscles take up glucose in greater quantities non-linearly. But it also takes time for muscles to adapt to this, a rate which is also non-linear.

Muscles not only consume glucose directly from the bloodstream, but they also tap into glycogen stores, a dense, compacted form of glucose (glycogen). These storage bins reside in both muscle (400g) and the liver (100g). When you exercise and tap into these stores, you need to eat glucose directly — yes, direct carbohydrates — to replenish these stores. This requires eating glucose—the liver cannot replenish glycogen stores by producing glucose. That would be just taking gas out of your gas tank in order to fill your gas tank.

You you need to each glucose to replenish glycogen stores, but that replenishment is also done via NIMGU. So, a great deal of glucose that you eat when you engage in exercise does not necessarily require insulin to offset it. Or the food you may need to eat after exercise. There’s a lot to this that we’ll address in my next article about exercise and T1D management.

The number of NIMGU was fully quantified in 2008, when an article published in Diabetes Care summarized it succinctly: “Most of the glucose uptake takes place in insulin-insensitive (brain and splanchnic) tissues,” with only ~25% occurring in insulin-sensitive muscle.

Stop and think about that for a moment. Your liver produces glucose “on demand”, but 75% of that glucose is going to NIMGU tissues, so only that remaining 25% will require insulin. That is where the proverbial “background insulin” can come in!

You can imagine what a tiny amount that is, relative to all the insulin you take all day, and the ratio of insulin to carbs.

Brace yourself for a ketamine-like surreal, mind-blowing fact: Given how rare and sporadic the liver produces autoregulated glucose, it should come as no surprise that our true basal needs are not only going to be exceedingly low, but there may well be periods where we don’t need any at all. As you may recall from the ZeroFive100 Project, one T1D had long periods of insulin-free gaps. So, let’s dive into that.

Clinical Scenarios For Insulin-Free Periods

Remember that the mere contraction of muscles takes up glucose via NIMGU, but that rate of uptake is highly dependent on how well trained the muscle fibers are. The more you exercise, the more trained they become, the greater the amount of glucose is cleared without insulin. But another aspect to this is that muscle fibers continue to take up insulin via NIMGU, even after exercise is over.

According to “Considerations in the Care of Athletes With Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus“ published in Cureus, “glucose uptake via NIMGU remains elevated for up to 48 hours” to restore glycogen to the normal level (for those who exercise regularly and have built metabolic resilience).

This is a complex topic that I’ll be addressing in an upcoming article that focuses specifically on insulin management for exercise. Suffice to say fr now, it’s not linear, and its complexity makes dosing a non-trivial problem. But, since exercise is the healthiest thing you can do to improve cardiovascular and metabolic fitness, it’s worthwhile.

The point being basal insulin can disrupt glycemic management unless all insulin intake is vastly reduced during and after exercise to account for all the various NIMGU processes involved.

Even walking, or possibly the occasional jog or bike ride, can have a big impact on insulin utilization and sensitivity. This was confirmed in the paper, Walking for Exercise, from Harvard’s School for Public Health, showing how insulin needs for meals are reduced when you simply walk for 15 minutes afterwards. The more basal insulin you may have onboard, the greater your risk of hypoglycemia.

The effects of exercise and glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity can be so profound that one can even achieve insulin-free gaps while maintaining normal glycemic levels. In an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine study “Increased Glucose Transport–Phosphorylation and Muscle Glycogen Synthesis after Exercise Training“ the authors demonstrate:

Glucose levels drop despite minimal or zero insulin on board

Muscle tissue pulls glucose directly from bloodstream via GLUT4 transporters (NIMGU)

Additional insulin would accelerate hypoglycemia by competing with muscle uptake

Brief insulin-free periods are physiologically appropriate and necessary

One concern is insulin’s roles beyond glucose control—its effects on protein synthesis, growth, cellular repair, and metabolic signaling (collectively called pleiotropic functions). True, but we’re T1Ds, so we face a tradeoff: Keep insulin onboard for these non-glucose related activities, or go hypoglycemic. As detailed in The Multiple Functions of Insulin Put into Perspective: From Growth to Metabolism, and from Well-Being to Disease, published in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, the authors conclude:

Brief interruptions don’t cause measurable harm in the pleiotropic functions.

The metabolic benefits of preventing hypoglycemia often outweigh temporary pauses in other insulin functions.

T1D patients already have disrupted insulin signaling patterns that make theoretical concerns less applicable.

Modern management allows for rapid restoration of insulin delivery when appropriate.

In fact, modern insulin pump systems don’t just tolerate insulin-free periods—they actively create them intentionally as a core safety feature. The MiniMed 640G, approved by the FDA and used worldwide, is a prime example. In the article, Hypoglycemia Prevention and User Acceptance of an Insulin Pump System with Predictive Low Glucose Management, published in Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, researchers showed that automated basal suspensions can prevent dangerous lows without increasing risk.

Similarly, in Usage and effectiveness of the low glucose suspend feature of the Medtronic Paradigm Veo insulin pump, published in the Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology, investigators concluded:

“Nocturnal suspensions substantially reduced overnight hypoglycemia without conferring an increased risk of morning ketosis, suggesting that routine measurement of ketones is not necessary in the context of automated pump suspension.”

The data speak for themselves:

40 patients experienced 2,322 insulin-free periods

Average of 2.1 suspensions per patient per day

Zero cases of DKA despite thousands of insulin-free gaps

Patients reported feeling safer, particularly at night

If the belief that the body requires “constant basal insulin” were true, these FDA-approved systems would amount to catastrophic malpractice. Instead, they mark the evolution of diabetes care toward intelligent, adaptive insulin delivery.

This shines a positive light on automation to be sure. And yes, this is a good thing, but the administration of that is, sigh, not that simple. There’s a difference between insulin suspension as a protective guardrails and ways to avoid hypos in the first place.

One of the limitations of AID systems that cannot possibly be overcome: They can’t see the future. They don’t know that you’re about to exercise unless you tell them. (Same with food, by the way.) And even if you announce food or exercise, it’s not just a matter of “saying” it, because the algorithm also needs to know when you ate last (for exercise), and how much so it can factor in glucose absorption and disposal in its calculation. Ideally, for all automated systems to work optimally, you always need to not just announce carbs, but break down the macronutrients, so the algorithm can more precisely calculate how to anticipate your glucose response.

What’s more, the variability that comes with exercise is widely erratic; even you don’t know how much exertion you’re going to do. For those who jog 30m every day have no doubt seen your heart rate vary, even if you’re going the same speed. This has a direct effect on energy needs, which directly affects NIMGU processes.

Indeed, many want to intentionally raise their glucose levels because it sustains endurance during high exertion activity (which is when your muscles burn glucose directly from the bloodstream in very high amounts). Here, they want to tell the algorithm to tolerate much higher glucose levels.

And none of this is limited to pump algorithms; the same applies to those on MDI (multiple daily injections), which we’ll also discuss in the next article.

Summary

You’ll notice that I mentioned we’d get back to night time basal needs, but I never did. And that’s because a great deal of it is covered by NIMGU, but really is best understood by talking about actual management techniques.

All of these situations will be covered in the next article, Basal Insulin Reduction: A How-To Guide using “Active Learning”.

The takeaway for this article that there are dozens of different processes and mechanisms that affect glucose production and absorption, in additional to insulin utilization, that makes this a hot mess if you’re trying to nail down basal rates.

And the three rules are most critical: Basal needs are not flat, basal ratios are not the same as basal rates, and the body absorbs a great deal more glucose via NIMGU than we think.

The benefit to lower basal dosing should now be clear: The less excess insulin you have onboard from basal dosing—regardless of the ratio—the easier it is to manage your bolus dosing.

With all this background, the next step is understanding how to reduce basal dosing wisely. For that, see my next article, Basal Insulin Reduction: A How-To Guide using “Active Learning”.

Interesting article and you have described perfectly a Stochastic system (chaotic and unpredictable with a multitude of variables - like the weather for instance). For less chaos and better predictability all stochastic systems respond favorably to decreased inputs to to the system in order to make output (results) more predictable and less chaotic. This applies to inputs such as food taken in in all of its types, exercise applied, and insulin supplied, stress experienced etc. The output (blood glucose level) then becomes more stable and predictable. There are many personal choices that can be made to lessen inputs and thus smooth chaos and in the case of diabetes, decrease danger of hypos and future complications of elevated glucose. Everyone will approach these choices differently, but we do have some control thank goodness. Complex system interacting with human behavior and intrinsic individual factors. Humbling stuff.

I can't wait for the next installment. I am MDI and have a workout program that would probably be considered heavy compared to the general population. Many days, I have feet on the floor, but I do not bolus to cover it, because any short-acting insulin will cause me to crash during my workouts. I have generally just used the workout to bring my sugar down. I split my bolus and vary it up to 25% at bedtime, depending on the intensity of my workout. Looking forward to reading your thoughts.