The Paradox of Low-Carb Diets: A1c vs. Metabolic Health

The conflict between glucose levels and metabolic health is unique for T1Ds

Most people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) are familiar with the mantra that a low-carb diet can be helpful in attaining lower A1c targets. It’s not just T1Ds—it’s everyone. Decades of research has shown that reduced caloric intake shows benefit for all mammals, not just humans, leading to longer and healthier lifespans. This is particularly important these days, as the rates of obesity are at an all time high. According to a study published in the Lancet, over ¾ of Americans are overweight, while the number of people with type 2 diabetes (including pre-diabetes) has doubled (since 1990) to well over 150 million.

As for T1Ds, of which there are nearly 4 million in America, the rate of obesity reached 37% in 2023 compared to only 3.4% in 1986, according to the Lancet article, “Obesity in people living with type 1 diabetes.”

Sugar is bad.

Bad, bad, bad.

This is why most T1Ds try—or at least, are told—to reduce their carb intake. One of the most familiar approaches is the Bernstein diet, which he describes in his 1977 book, Dr. Bernstein's Diabetes Solution: The Complete Guide to Achieving Normal Blood Sugars. In essence, Bernstein recommends no more than 30g of carbs per day. (A longer summary and analysis can be found in the article, “What Is Dr. Bernstein's Diabetes Diet?”)

On the one hand, those who follow his diet (and other variations of it) have been successful at lowering A1c levels.

On the other hand, it’s not that simple.

Over the ensuing decades, low-carb diets, including ketogenic diets, have been put to the test in thousands of clinical studies and trials, leading to significant refinements about what is considered “healthy,” not just for T1Ds, but the general population. While low-carb diets helped reduce A1c levels, the studies also revealed the potential drawbacks. In the 2019 comprehensive literature review, “Low-Carb and Ketogenic Diets in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes,” over 100 peer-reviewed papers, studies, and books that spanned hundreds of thousands of people over decades paint a constellation of risks. Highlights include:

Those on low-carb diets generally have significantly higher levels of low-density lipoproteins (LDL) substantially increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases, largely because of increased intake of high-fat foods. (Most low-carb diets warn about this, but people will be people.)

Children on low-carb diets are more prone to anthropometric deficits, and an increase in the risk of eating disorders, especially among adolescents.

T1Ds on low-carb diets statistically suffer higher rates of hypoglycemia, as well as euglycemic DKA (diabetic ketoacidosis with normal glucose levels), due to insufficient glycogen stores.

Compliance rate is low, with most failing to adhere to the diets after two years, triggering a severe rebound effect, where their T1D management was worse than before attempting the diet.

The psychological burden of managing both T1D and a highly restrictive diet has been found to lead to mental health disorders.

More importantly than all of those, and also far more prevalent, researchers found that nearly all T1Ds on low-carb diets are metabolically unfit, even among those whose average glucose levels were at or below recommended targets, leading many to die prematurely from all-cause mortality.

These are all why major medical organizations, including the American Medical Association, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and the American Heart Association all recommend AGAINST low-carb diets for T1Ds.

Wait, you’re wondering. How can this be? I thought keeping A1c levels really low was healthier.

Well, yes, lower A1c levels are healthier than higher levels, but that’s not the only factor governing your health and longevity. Hence, the paradox of low-carb diets: They certainly help reduce glucose averages, but at the expense of compromising a critical life function: Your metabolic health.

Besides, there are many other, better, easier, safer, more enjoyable and healthier ways to lower A1c levels than low-carb diets.

This article does not cover ways to keep A1c levels low and stable. For that, see my article, Self-Identity and the Four Habits of Healthy T1Ds. Rather, this article is solely focused on how to improve metabolic health, and glucose lies at the heart of that.

Most people don’t really know what the metabolic system is, and endocrinologists never mention it to patients, largely because it’s very complex and highly individualized. It would take far longer than the fifteen minutes you’re allocated by your insurance plan, and you need that time to complain to your endo about how hard it’s been to stick to a low-carb diet.

The Metabolic System

In short, the metabolic system is an energy conversion mechanism in our bodies that is responsible for converting fuel (glucose) into energy that makes life happen: building and repairing tissues, fighting infections, generating proteins and amino acids, your entire immune system, protecting against cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and inflammation. The list continues. Those with poor metabolic systems have a much harder time performing these tasks and generally have much shorter lifespans.

Bottom line: Building a “healthy” metabolic system requires exercise, much like how building muscles requires pushing them to their limits briefly. Stressing the metabolic system in a healthy way is where glucose’s role is important, and that’s what makes things tricky for T1Ds.

The tie-in with T1D is that the kind of exercise that improves metabolic health requires a level of carbohydrate consumption that goes against the low-carb diet mantra.

Now, that’s not to say that consuming copious amounts of sugar is good. The sugar has to be balanced with the amount of exercise you do. The more exercise you do, the more glucose you need. Unlike with non-diabetics, who can store consumed glucose and release it when needed, T1Ds can’t do that quite as efficiently (and it varies among individuals). So, it’s the timing of when you consume glucose that matters for T1Ds who exercise.

We begin with how the metabolism uses glucose.

Carbohydrates and The Metabolism

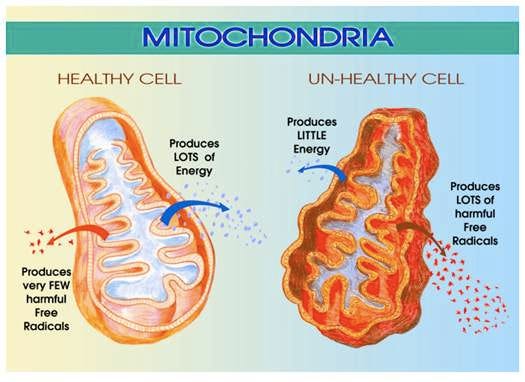

Within most of our body there are tiny organelles called mitochondria that act as energy-conversion mechanisms, much like how a car’s engine converts fuel into energy.

In a biological life form—like a person—mitochondria create energy by oxidizing molecules, primarily glucose and fatty acids. The better and more efficient this process, the healthier the cells that receive this energy, translating into a better ability to fight infections, repair tissues, build new proteins and amino acids, etc. When mitochondria are weak, they can’t do these tasks well enough to keep you healthy, or even alive, if they can’t stave off certain diseases (cardiovascular, kidney, etc.).

In short, a weak metabolic system is bad.

What strengthens mitochondria is exercise. This excerpt comes from the literature review article, Metabolic Flexibility and Its Impact on Health Outcomes:

“Regular physical activity stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis, the process by which new mitochondria are formed. Aerobic exercises, like running and swimming, and resistance training can enhance mitochondrial efficiency and increase their numbers, improving overall energy production and stamina.”

For a really detailed and fascinating “view” of these, see the post from the substack, Physiologically Speaking, “Mitochondria Aren’t Just Energy Factories—They Take on Dual Roles to Meet Metabolic Demands.”

The efficiency in which your body converts fuel into energy is your metabolic fitness. And this can be quantitatively measured by a lab experiment where the amount of oxygen you inhale is compared against the amount of carbon dioxide you exhale. Here, carbon dioxide is the byproduct of that energy conversion.

As physical exertion increases, the amount of oxygen needed to convert lipids into energy is insufficient for the physical demand, so your fuel source begins to gradually start using glucose as the primary energy source. This also produces more carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

When the level of carbon dioxide you exhale crosses a particular threshold, you’ve reached your “maximum oxidative capacity,” which which point, you no longer burning lipids for energy—you’re burning only glucose.

That is your V02max: the maximum (max) volume (V) of oxygen (02) you can utilize during a specified exercise.

It’s also how mitochondria grow, both in efficiency and in quantity. As exertion increases, the organelles multiply.

Where things get really tricky for T1Ds is that our bodies don’t regulate blood sugars automatically the way it does for normoglycemic individuals, otherwise known as “non-diabetics.”

If we T1Ds don’t have enough glucose in the bloodstream, we can’t exercise sufficiently to improve our metabolic fitness, or worse, we can suffer severe hypoglycemia.

So we need to manage our glucose levels by taking into account more than just insulin intake—we also need to consider the glucose that’s consumed by exercise itself (not insulin), and the ADDITIONAL GLUCOSE that the body introduces into the blood supply on its own (from storage). This is where things get tricky for T1Ds.

Glucose and Exercise

To set the stage for this, remember what insulin does: When it lands on cells, it signals GLUT4 transporters to rise to the surface of cells, allowing glucose to pass through directly from the bloodstream. This is why we take insulin for food we eat: to absorb glucose from the bloodstream.

If you do zero exercise, it’s like a car sitting the driveway that’s idling, but with the brakes on and the gear in neutral. The car is running, but there’s no movement.

Taking a walk or doing activities that are not that demanding does not require that much glucose, so the body can get it by fat oxidation. So long as the physical demand does not exceed the body’s capacity to oxidize enough fat.

Once physical demand rises beyond that oxidation threshold, muscles need to get sugar from somewhere else. It’s either in the bloodstream already, or muscles go to their own storage containers that contain glycogen. If there’s not enough glycogen in those stores, the muscles can’t do the work, the person fatigues quickly and stops. More often than not, however, the muscles keep drawing glucose from the bloodstream, and this is where the risk of hypoglycemia arises.

Now, here’s what makes things very dangerous for T1Ds: muscle contraction also causes GLUT4 transporters to rise to the surface of cells, just like insulin. Yes, that’s right—the muscles are doing the same thing as insulin, and the more physical activity you do, the more glucose will be drawn from your bloodstream from BOTH insulin and muscle contraction at the same time. That’s a huge sink for glucose disposal, which can deplete the glucose supply too quickly, resulting in severe hypoglycemia.

This is why most T1Ds don’t exercise. And it’s hard to teach them how to exercise properly because the science is rather complex, and it’s highly individualized. It’s not easy to provide step-by-step instructions—everyone’s metabolic rates and performance varies.

That said, let’s look at how T1Ds can manage this better.

Insulin dosing changes with exercise

Because both exercise and insulin can clear glucose from the bloodstream, T1Ds need to reduce insulin intake long before starting to exercise.

How much to reduce is not calculable, and it varies—sometimes by a lot—so it’s an imperfect, but achievable, artform that requires trial-and-error experimentation (while being safe not to go hypoglycemic).

Remember when we learned that mitochondria grow and become more efficient with exercise? Well, that improves insulin sensitivity, so as mitochondrial fitness improves, insulin sensitivity goes up as well. That even further reduces the amount of insulin you need. This is gradual, as it take time (weeks or months) for your mitochondria to adapt, but it does happen, and you’ll see that from a continued drop in insulin dosing.

Glucose dosing changes with exercise

Then there’s the glucose: As your exercise improves, you’ll burn even more glucose.

Next, the body has two ways to introduce additional glucose beyond what you eat. As mentioned earlier, muscles have “glycogen stores,” which are pockets within the muscle fibers that contain a compacted form of glucose. These storage containers fill during feeding times, so long as you eat sufficient carbohydrates to fill them.

When muscles are physically stressed beyond the point where they can’t oxidize fat sufficiently, muscles signal the glycogen stores to release glucose into the bloodstream. This happens to everyone, regardless of whether they have T1D.

Note that for T1Ds, this release of glucose into the bloodstream will cause blood glucose levels to rise! This surprises many T1Ds, who expect their glucose levels to drop. But this is a short-term spike, because the muscles need that glucose and will reabsorb it right away.

As will be shown in graphs later, one might see a sudden rise in glucose levels followed by a subsequent fall. Note that when you’re done exercising, this new excess glucose that was released into the bloodstream from the glycogen stores won’t be utilized, so it’ll stay in the bloodstream, so glucose levels may rise and stay up.

Here, a T1D would need to take insulin. How much is entirely trial and error. There is no way to calculate, and there are no other biomarkers to test to evaluate how much is needed.

Since my mitochondria is “well-trained”, my CGM data can illustrate this well. I usually do a 3-mile run every morning. Below are my glucose levels, my carb and insulin intake:

I wear an apple watch, so I can also track how much actual activity I was doing, based on my heart rate zones:

While I won’t get into the details here, the five zones refer to the degree in which mitochondria oxidize fatty acids to get glucose (zones 1 and 2), which is “aerobic,” versus burning glucose directly (zones 3-5), which is “anaerobic.”

The nuance here is that zone 3 is just the beginning of the anaerobic process. The body will do both (oxidation and direct utilization of glucose) in zone 3, but as you approach zones 4 and 5, the mitochondria progressively favors anaerobic consumption. Zone 5 is 100% anaerobic.

In practical terms, one cannot sustain anaerobic activity for very long—there’s simply not enough fuel. Moreover, while direct burning of glucose provides a quick and powerful punch, it’s highly inefficient, so it doesn’t last long. It’s like using kerosine to light a fire: quick and combustible, but it doesn’t last long.

If you exercise enough to deplete the glycogen stores in muscles, a normal body would then trigger the second source of glucose: a process called gluconeogenesis, where the person’s alpha cells in the pancreas produce glucagon, a hormone that signals the liver to produce and release glucose into the bloodstream.

But alpha cells only produce glucagon with signaling from beta cells, which don’t work in T1Ds. So, we TDs have alpha cells that just twiddle their thumbs because they are totally unaware that glucose levels are low. (There are exceptions to this, but it’s beyond the scope of this article and only applies under non-exercise related extreme conditions.)

The only (and best) way to get that extra glucose is by EATING it—the simpler the carbs, the better because it absorbs more quickly and efficiently. That’s why I ate 18g of simple carbs before my run.

Summing it up: To improve metabolic health, you need to exercise, and when you do, you take less insulin, and eat more carbs.

How many carbs?

Hard to know! Every person is different, and every day is different. But look at it this way: Normally, I would have to take about 10u of insulin to cover the dawn effect till around 11am, assuming no other carbs or exercise. Since I didn’t have to take that insulin because I ran, we can back-calculate the carbs my body produced. My insulin-to-carb ratio is 1:15, so if I would normally take 10u, but I only took 2u at 8am, then that’s 8u that I didn’t take. 8x15=105 — so that’s 105g of glucose I burned during my run. Take into account that I ate 18g before I started, that means I must have drawn 105-18=87g of carbs directly from my glycogen stores in my muscles.

Keep that number in mind… 87g of sugar.

Now, remember when I said “eating replenishes glycogen stores?” When you eat food, glucose is distributed to different parts of the body at different rates and at different times. Glycogen stores are often replenished at night, during sleep.

Critically, glycogen stores are replenished without insulin mediation. That’s right, glucose is sucked directly from the bloodstream and delivered into the storage bins next to those muscles that used it.

Now let’s remember that 87g of carbs that I used during exercise. That came directly from my glycogen stores, so I need to eat at night so assure that those stores are replenished, and I need to be sure I don’t have insulin onboard that would otherwise redirect the glucose away to somewhere else, sending me into hypo-land.

Below is a BG graph of that night, so let’s see if the numbers match up:

You can follow the detail in the icons to understand what’s going on. I had to eat several times during the night (about 54g carbs) to replenish my glycogen stores, but also notice that I still had two severe lows (50 mg/dL). Yes I had carbs, which entered my bloodstream pretty fast (because they were Gu energy gels, which is maltodextrin, the fastest acting carb you can consume), but as you can see, those glycogen stores were still sucking glucose from my bloodstream afterwards, so BG levels dropped again, and I had to do another 8g of carbs at 4am.

That gets pretty darn close to that estimate of 87g we came up with before.

Now, the fact that I had two severe lows is no bueno!!! I shouldn’t have taken the 1u of insulin at 9pm, but this was a bad call on my part. Fortunately, that’s very unusual. A more typical night looks like this:

Dinner was roughly 80g net carbs at 8pm. Before bolusing for it, I wait till my glucose levels start rising, because ya never know if food decides to absorb more slowly, or there are other anomalies at play. Once BG levels started to rise around 9pm—a whole hour later!—I took 6u of humalog, and did a mild walk for about 15 minutes (which helps with insulin absorption).

Then at 10pm, I had 35g more carbs, but in that case, those were all nuts (walnuts, almonds, macadamia) because all that fat is like a slow basal dose of carbs that last for hours during sleep. Those fats convert to glucose, which is then absorbed by the glycogen stores.

Ok, lesson over. Take a breath.

All this feels like a massive contradiction for what we learned (and continue to hear) about T1D management. They drill the mantra into you: “Take insulin for food, and avoid carbs.” To be sure, this is true for those who don’t exercise, or times when you’re not exercising. But it’s not the case while you’re exercising (or about to). It’s a complete mind-melting experience, and it’s often met with resistance, if not direct skepticism, so many T1Ds suffer from poor metabolic health. And that’s very bad.

You can now see how this energy demand requires consumption of carbs that violates the low-carb guidelines.

Ideally, you want glucose levels to meet the demand from exercise, so your average glucose levels remain within target ranges, even if you have a spike before or during exercise. This is a manageable problem, especially once you get the hang of it. Since it’s far more important to avoid hypoglycemia, it’s better to err on the side of elevated glucose levels here.

If you stick with it, it’s not nearly as hard as it might appear.

Measuring V02max

Below is a chart that shows each of the five stages of metabolic fitness, with “Above Average” highlighted in pink. (The open area under these levels is “poor” and the area above is “elite.”)

Below is a chart of my own journey incorporating exercise into my T1D management.

In June, 2019, I started on the Dexcom G6, which was the first CGM I ever wore. The mere fact that I could actually track my glucose levels in real time is what made all this possible, and it helped me reduce A1c's simply because I started to pay attention.

In March, 2020, when the world was shutting down because of COVID, I read those articles about the metabolism and decided to start running, while also carefully logging both carbs and insulin to see how my carb/insulin absorption rates evolved during exercise.

When I started, my V02max was 34.9, the low end of average, but by January, 2021, it came up to 43 (above average for my age). I also lost ten pounds. Today, my V02max is nearly 46, which is in the “High” tier, and my A1c hovers around 5.5%. (And I just turned 62 on Nov 20. Yay me.)

For what it’s worth, I have only been able to achieve this level of fitness because I run 3 miles/day, and walk for 20-30 minutes after each meal. (I also hike.) And there’s no way I could do any of this on a low-carb diet. Below are 90-day stats from Sugarmate:

You’ll see that my average carb count is quite high at 400g/day, but it’s important to note that my exercise is burning off most of those carbs—not insulin. Also, I count carbs by including fats and proteins, not just the number of “carbohydrates” grams you see on nutrition labels on food packaging. So, it’s 400g “net carbs.”

I’ve seen similar patterns in other T1Ds who exercise a lot, but I’m well aware that most T1Ds don’t (or won’t) attempt this (for a variety of reasons). And not everyone who exercises has super-low A1c levels. That’s ok—it’s not all or nothing. One can still gain considerable health benefits by doing less than “elite” levels of exercise. Anything is better than nothing, which many studies have shown, so let’s take a look.

Metabolic Fitness and Diabetes

Weighing the risks of elevated glucose against the benefits of a healthy metabolic system is the primary focus of my article, “T1D and Health: How Long Will You Live?” There, I cite a number of studies that explored the various risks of all-cause mortality for T1Ds at different metabolic fitness levels.

One is this 2015 paper, “Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness With Long-term Mortality Among Adults Undergoing Exercise Treadmill Testing,” involving more than 122,007 adults between 1991 and 2015. The authors found that more metabolically fit people had longer lifespans, even in the presence of other comorbidities, such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, or even smoking and diabetes.

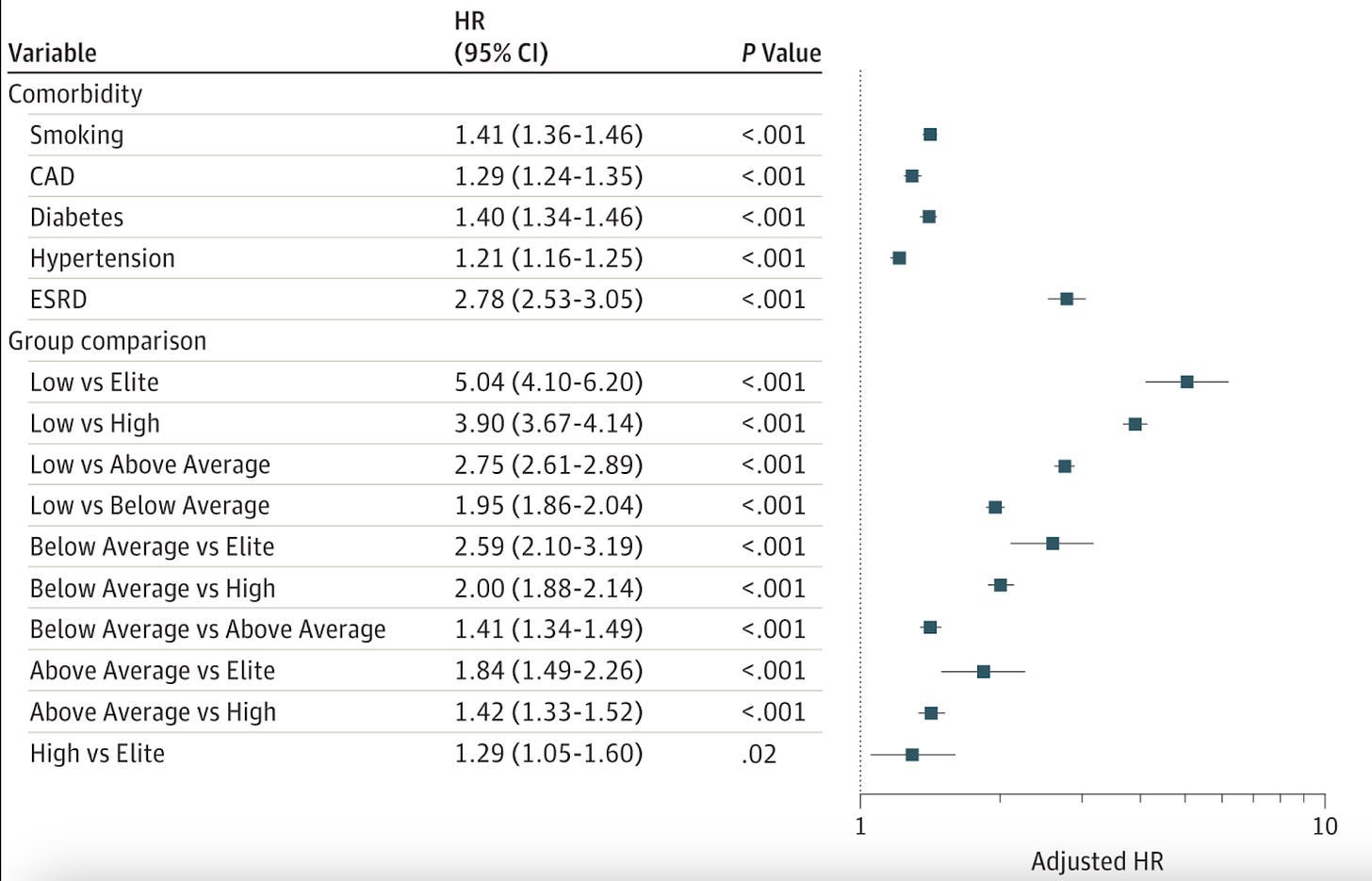

The following chart illustrates the “hazard ratio,” which is defined as a weighting for how much more likely you are to die from all-cause mortality. The higher the number, the greater the risk. Note that Diabetes (1.4) is roughly equal to smoking (1.41). (ESRD is end stage renal disease, or kidney failure.) The section labeled “Group comparison” shows the risk of all-cause mortality is greatest when the cardio fitness is low (vs elite) by five orders of magnitude.

You should read the article for the gritty details, but since you’re here, look at the right side of the chart in the area labeled “Adjusted HR” at the bottom. This is the Hazard Ratio adjusted for different levels of metabolic fitness: The further to the right, the lower your overall risk of dying early. If you were an elite athlete, your risk of dying from all-cause mortality is 5x lower than if your metabolic health is poor, even if you have diabetes or you smoke. That’s huge, but it also involves being an elite athlete, which may be out of reach for many.

But you can get excellent benefits at even modest improvements of metabolic health, even by just being “Below Average,” which may involve something as simple as a 15-minute walk after each meal. At this level, there’s still a 2x reduction in your risk for all-cause mortality versus a poor fitness level. Again, even if you have diabetes.

This was also confirmed in the paper, “Walking for Exercise,” from Harvard’s School for Public Health, showing that you can add several years to your lifespan.

Imagine being rewarded so nicely for being “below average.”

The alert reader may be thinking, “Yeah, but A1c levels can be all over the map. Surely, those whose A1c is 7% have a much better risk profile than those with an A1c of 9%, right?”

Fortunately, that’s been studied too. A lot.

The literature review paper titled, “Why do some patients with type 1 diabetes live so long?” cites multiple studies that find that cardiovascular health is the predominant determinant for longevity among T1Ds, even among those with elevated glucose levels. One study is the “Golden Years Cohort,” which includes 400 T1Ds who’ve had the disease for over 50 years were in excellent metabolic health, while also having a mean HbA1c of 7.6% (± 1.4), with some levels as high as 8.5%-9%. None had an HbA1c below 7%.

By contrast, of those who happened to die early from cardiovascular disease, kidney dysfunction, and other metabolic problems, many had A1c levels below 7%, which comport with ADA recommended targets, but also comporting with the results from the Treadmill study cited earlier: They had low metabolic fitness.

My summation is this:

The trap that T1Ds get into is the belief that attaining “target” or “ideal” glucose levels is itself “healthy.” Well, yes, but only by comparison to levels that are higher. This is like saying that smokers can live longer if they quit or reduce their level of smoking. Again, yes, but only by way of not dying earlier. If you quit smoking—or achieve non-diabetic glucose levels—you just bring your life expectancy back to baseline, where your risk profile is governed by your metabolic fitness. While reducing risk is good, your real goal should be to add to your lifespan beyond the averages by engaging in activities that improve your metabolic fitness.”

Accordingly, treatment in people living with T1D is beginning to shift towards improving overall metabolic health in parallel with attaining lower glucose levels. One example is this article about how Belgium is focusing primarily on metabolic health for T1Ds, with glucose control as a secondary goal.

It should be noted that this is not a green light to throw caution into the wind by allowing your glucose levels to run amok. If you’re not going to exercise, then yes, a lower A1c level is far better than a higher A1c. Let’s not fool ourselves.

The real goal is to exercise to improve metabolic health, and it turns out, if you do raise your fitness to average or even above average—which may involve jogging a couple days a week—then you’ll inadvertently find that your glucose levels will trend downward.

Measuring your metabolic fitness

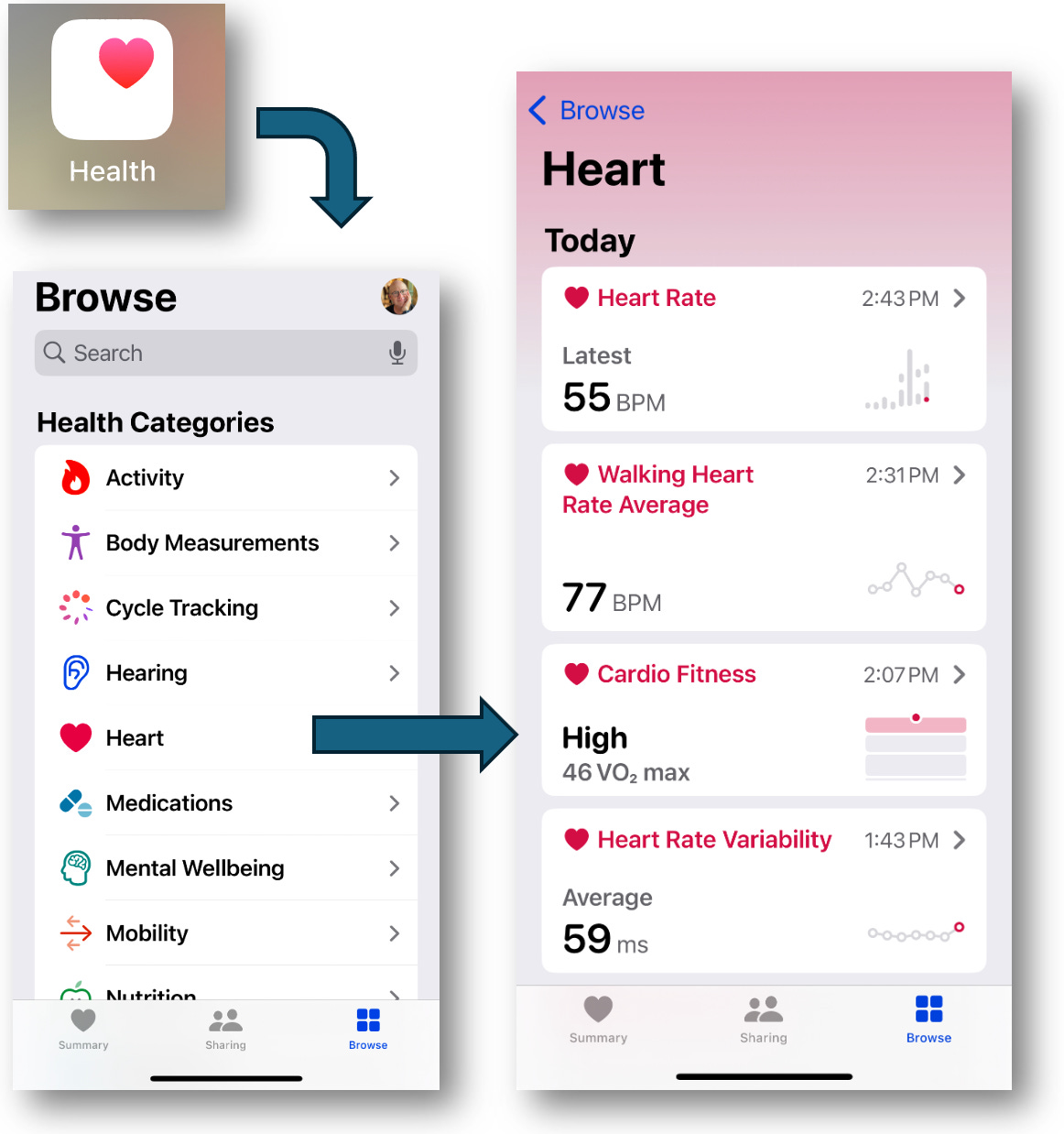

As mentioned earlier, metabolic fitness is measured using V02max, and you can do this test on your own.

The easiest way is using an Apple Watch, but if you don’t have one, you can do most of the same thing with other products that can measure your heart rate. You can take the one mile walk test. The page explains how to do it (walk for a mile while measuring your heart rate), and after you input the data, your results will be normalized for your age and gender. It’s a very common test, so you can find the forms everywhere online.

If you have an Apple Watch, your heart rate is stored in Apple Health, and your V02max is automatically calculated for you. You can find this in the Health app, as shown below. (This is from my phone, so you’ll see my data in the various sections listed on the right.)

If you touch “Cardio Fitness,” you should see a chart like the one shown below. If you don’t, then you’ve never recorded a workout, or not enough of them for the algorithm to come up with an analysis. If that’s the case, add the “Cardio Fitness” to your Favorites using the Heart icon, and the data will be recorded for future activities.

Learning how to eat (carbs) and dose (insulin) properly for exercise is a whole different topic, far too involved and complex for this article. But to put you at ease, you don’t need to know all the gritty details I explained in this article to succeed. Start walking, running, jumping, cycling, swimming, having babies, or anything that moves you around.

As for your diet, eat properly, get enough nutrients, fiber, protein, and of course, carbohydrates—a sufficient amount that balances with energy demand. Watch your CGM and just pay attention. This is such an individualized pattern, that even if you find guidelines (which vary a lot from sources everywhere), your own experience will be unique. The good news is, you’ll figure it out if you are diligent, and you’ll be healthy, which is really good.

Good. Good. Good.

FYI: There are other things that I do to keep healthy, which you can read about in my article, “Why I Haven’t Died Yet: My Fifty Years with Diabetes.”

It sounds like you are doing great, so congratulations ! In general, I find no fault with your summaries of metabolism, or your conclusions. 5.8 is an excellent HbA1c. You'll know in 3 decades whether it's "good enough" . LOL. However

There are a couple of points that I would like to add:

> Adjusting to the low-carb diet takes some time. See the publications of Volek and Phinney.

>Dr. Bernstein has recommended -maybe on his Webinar- taking glucose during exercise. For him, this might amount to something like 2 grams glucose every half hour of exercise. NOT to correct going low, but to avoid going low. For some of us, this is not so fine-tuned, so it might be more like one tab of glucose (4 g) maybe something like 15-20 minutes before a nice brisk walk. Maybe more glucose later if the walk is long.

> A regular exercise program will of course result in the need to lower one's basal insulin dosage.

Yes, it is ironic that for a diabetic on a low-carb diet, taking glucose is a necessity. My readings on diet suggest to me that attaining a ketogenic state is not even possible for a T1D keeping blood glucose levels low, and correcting with glucose, because taking glucose would quickly catapult one out of ketosis.

Well, enough for now. I completely agree with you on the importance of exercise, and I believe that it sustained me for decades before I discovered Dr. Bernstein, but for me as a T1D for so long a time, I continue, as of now, to consider low-carb as one of the foundations of my self-management.

Very thorough as always, Dan! Thanks for your work. Regarding exercise, there seems to be a lot of confusion in the T1D world about how exercise will affect an individual. Some people report that their BGL drops like a rock, while others report that they stick high. Is this a case of people generally not understanding the difference between aerobic vs anaerobic exercise? Is it really as simple as "anaerobic exercise will reduce your BGL 100% of the time"? Perhaps when people describe "exercise", they are painting with too broad of a brush, considering that could be any number of activities that differ extremely, from a metabolic perspective (e.g. walking vs. sprinting vs. weightlifting).