The Best Way to Treat Hypoglycemia

Treating hypos incorrectly has both short term and long term consequences

To listen to the podcast edition of this article, click here.

Whenever I’m with a group of T1Ds, someone invariably brings out some kind of product to treat their low blood sugar—the point where glucose levels drop below 70 mg/dL, also known as hypoglycemia. Parents of their T1D children give them a juicebox, while adults might snack on an energy bar, apple sauce packets, yogurt, juice/soda or some other sugary drink.

While all of these elixirs will do the job (eventually) each has effects that may make them less effective than they should be, and worse, could cause undesirable side effects later, both short term and long term.

Because it’s nearly impossible to properly know (or even estimate) the exact amount of glucose needed for a hypo event, most people eat more than they need, which is understandable—hypoglycemia is akin to torture. Yet, over-compensation often leads to the dreaded glucose roller coaster: Sugars skyrocket too far, thereby requiring insulin to correct, which is also too much, and into the loop part of the roller coaster we go. The rest of the day (or night) is spent trying to return to homeostasis. This is the worst “experience” in T1D (apart from DKA, I suppose).

Some are so fearful of hypos that they just keep their sugars higher. Dangerously so. “Fear of hypoglycemia” (FOH) is such a serious phenomenon, it leads not just to poor control, it triggers psychological distress, and keeps people from exercising, perhaps the best and most important way to manage diabetes.

There’s quite a bit about hypoglycemia that could be addressed, but this article really narrows it down to one thing: the best way to treat it. But along the way, we also have to learn some physiological aspects about it, not just because it’ll help you better understand why the treatment works, but it will also unmask a lot of misunderstandings about hypos that may make you less afraid of it.

Let’s start with the basics.

Ye Olde Nervous System

Let’s return to that gathering I mentioned earlier, where T1Ds use different ways to treat their low glucose levels. The reason each of these choices—from juice boxes to energy bars—are not ideal for treating hypos is because of how these foods are processed in the gut. Even though people think they’re absorbing “fast” carbs, it turns out to be a lot more complicated than just that. So, let’s go into the gut.

Everything you eat goes through a process called gastric emptying, which is characterized by the rate at which the stomach delivers its contents to the small intestine, and how the body processes those contents. Let’s start with how things are supposed to work.

In non-T1Ds, when glucose levels drop too low, the sympathetic nervous system responds in two ways: First, it accelerates gastric emptying, facilitating rapid glucose absorption. So, if someone (say, an athlete) runs low on glucose, they can slam down an energy gel and all’s well. Keep this in mind, as it’s an important element that will come up later.

Secondly, the sympathetic nervous system signals alpha cells (that sit next to beta cells) to produce glucagon, a hormone that signals the liver to produce glucose (gluconeogenesis), which raises glucose levels. To prevent blood glucose levels from bouncing around, the body synchronizes its insulin and glucagon secretion to be in tight communication. This is why the alpha and beta cells are physically next to each other in the pancreas—they talk to each other.

This tight ecosystem of signaling is largely how a non-T1D body maintains glucose levels.

But in T1D, the beta cells are dead, so this communication is broken, and it leads to a cascade of problems that, over time, waterfall into a progressively difficult state of affairs.

Cascade of Problems: Neuropathy

I need to emphasize that this section describes the effects that happen very slowly over time. Many newly diagnosed T1Ds, especially children, do not experience much of what’s described here—but they will. One can delay this cascade with tighter glycemic control and—especially—exercise, which protects nerves (and other tissues) from assaults, but also aids in healing.

But, even in the best circumstances, higher glucose levels lead to neuropathy, particularly the sympathetic nervous system.

Digestion is governed by the sympathetic nervous system, so when it’s damaged from years of hyperglycemia, it slows down gastric emptying in ways that are unpredictable and volatile, often without notice. When the condition surpasses a particular threshold, it’s classified as gastroparesis, a condition affects approximately 28% of T1Ds, according to the paper, Prevalence of delayed gastric emptying in diabetic patients.

While gastroparesis may only affect ⅓ of T1Ds, remember that the formal diagnosis is a threshold that misses a much larger percentage of T1Ds whose symptoms are more mild. Statistically, anyone that’s had T1D over 10 years already have some degree of it. Five years is common, but is highly dependent on not just glycemic control, but weight management and—again—exercise.

Making matters worse, gastric emptying can also be slowed by hypoglycemia. This is the biphasic nature of the intestine and the nerves that govern it—in non-T1Ds, hypoglycemia can increase gastric emptying, but when T1D sets in, the process can reverse, slowing down absorption. For T1Ds who already have some degree of neuropathy, hypoglycemia-induced slowed gastric emptying can be range from 30–50%.

Wait, there’s more! If your hypo-treatment elixir also includes any amount of fat or protein—such as protein bars or chocolate or, well, most anything—those ingredients will delay absorption even more than gastric emptying will (for reasons beyond the scope of this article). What’s more, proteins and fats will cause glucose levels to rise later, long after the sugars already had.

So, let’s quickly return to that gathering of T1Ds that are treating their hypos by eating candy, or apple sauce, or honey, or whatever they have around. The slowed gastric emptying allows some, but not all, of the carbs in. So, there’s a feeling of recovery, but the person is unaware that only a small portion of those carbs did the trick. The rest are still sitting in the intestine, waiting. And you know what comes next: the huge spike, and the roller coaster.

Let’s also not forget how the hypo happened in the first place: misalignment of carbs and insulin dosing.

As you’ve no doubt learned when you were diagnosed with T1D, you take insulin (or you rely on pumps to administer it) alongside food intake. And that’s just the bolus insulin. You also have basal insulin onboard—you know, the old background insulin that’s supposed to take care of metabolic activity that doesn’t involve food. Most people don’t factor in the basal insulin (long-acting for MDI users, or the steady drip from an insulin pump) for food because you’re not supposed to. It’s supposed to be in the background.

The problem is, most people take too much basal insulin, a problem that’s been around for decades and has led to a sharp rise in obesity and hypoglycemia. For a detailed—and critically important—discussion, see my article, Ye Olde Basal Rate: Its Effect on T1D Management and Long Term Complications. With excess basal insulin onboard, it’s lowering your glucose levels in unexpected ways, leading to even more hypo events.

Since this article focuses only on the food absorption part of all this, we’ll set aside the insulin absorption and basal factors for now. But be aware that they are a critical part of this process.

Insofar as food and insulin absorption, this is why children do exceptionally well, because they haven’t had the time to develop the dysfunctions.

As time passes, glucose levels are just naturally higher. Worse, glucose levels bounce around on the glycemic roller coaster (a process called glycemic variability, or GV), the progression of neuropathy accelerates.

As time goes on and T1Ds begin to experience systemic volatility, the rate in which that food is absorbed becomes even more volatile, putting insulin dosing out of alignment with carb intake. Complicating matters even more is when basal rates are set too high. And when insulin and carbs are out of sync—even by a tiny amount, say, 30 minutes—you get the big crash: hypoglycemia.

Just because you’ve counted carbs (and told your insulin pump), it doesn’t mean that you know how much of those carbs have been absorbed, or when it might. You can’t know that. As time goes on, it becomes increasingly less predictable. If you use a T1D app that attempts to present how many carbs are “on board,” do not trust it.

The same is true of “insulin onboard”, or IOB. Insulin absorption variability also gets progressively volatile over time, due to lipodystrophy (damage to tissue where insulin is injected or infused).

“Delayed gastric emptying” becomes a major, but ghostly factor in T1D management: It’s there, but it’s very hard to see. Shoving a lot of “fast carbs” into your gut is like filling up your car with gas, only to find that the fuel line isn’t letting the gas get into the engine.

The result: Hypos happen more frequently, are more severe, and are harder to treat.

As neuropathy further erodes, it leads to hypoglycemia unawareness because the nerves just aren’t there to make you aware that your glucose levels are low. People can be as low as 40 mg/dL and feel perfectly normal—until their car careens off the side of the road. Not so normal anymore.

Ironically, the horrible, horrible feeling from hypoglycemia is a sign that you still have function in your sympathetic nervous system, even though it may have some impairment. But if the fear of it causes you to keep your glucose levels dangerously high, that will actually bring further harm to your sympathetic nervous system.

This all brings us back to the best way to treat hypoglycemia in ways that get around all these problems.

The solution: Avoid the gut completely

When gastric emptying is slowed, the absorption of orally ingested carbohydrates is delayed, so the best thing to do is avoid the gut entirely. That’s right, you can use glucose tablets or gels composed of Dextrose and follow these simple steps:

Chew up some number of tablets (or squeeze gel under your tongue) and try not to swallow. (This part requires practice because you really want to swallow.)

Redirect the saliva-laden granules to your cheek pouches and under your tongue (oral mucosa).

Hold in place for at least 1–2 minutes—but longer, if you can—before swallowing.

How many grams you should consume varies—we’ll get to that shortly—but it’s important to understand how and why this process works, and why it helps avoid the other problems discussed till now.

There is a lot of vasculature in the oral mucosa, and since dextrose is a very small sugar molecule, it can be absorbed directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract entirely.

This is as close as you can get to the timing of a non-diabetic glucose correction short of being hooked up to an IV and having dextrose manually administered.

And for clarity, “dextrose” is formally “glucose” (D-glucose), which is not the same as the kind of simple sugars that most people call “glucose”. It’s a word/phrasing thing that can confuse people.

Anyway, the primary benefits of using dextrose in the mouth include:

Bypassing your intestines assures that these carbs will be absorbed as quickly as feasible.

Dextrose is in and out of your system—fast. Once absorbed, you’re done. There’s no risk of extra carbs that will get absorbed later, leading to the roller coaster.

Speedier absorption makes it less likely that your counter-regulatory system kicks in (assuming it’s working). Hence, you’re less likely to get the roller coaster effect (or if you do, it’ll be much more mild).

Because tablets only contain 4g each, it’s harder to over-compensate by eating too much. This is good, because, more often than not, you don’t need as much as you think (though the panicky feeling doesn’t make you feel that way). The limited speed in which you can consume tablets (using this technique) helps limit over-compensating. Now, instead of ravenously wolfing down that box of girl scout cookies you’ve been eyeing, you’re being slowed down by a more direct and sensible method.

Note that “gel” versions of Dextrose are also available (e.g., “Insta-Glucose”), which make it easier to get under your tongue, but they generally come in larger tubes or packets (15-24g each), so it’s not easy to get a smaller dose if you want one (without losing accuracy). The tablets are ~4g each, so if you want accurate dosing at lower quantities, that may be a better option.

Let’s move on to how dextrose compares with the more common and conventional way people raise their BGs.

Comparing dextrose with other carbs

If you do not have Dextrose when your sugar is low (I’m administering a stern look of disapproval), then you have no choice but to eat something else. And yes, for anything other than dextrose, you have to swallow it. The oral mucosa will not absorb any other form of sugar because those molecules are too big to pass through the membrane. So, trying to keep sugary soda or juice in your mouth will not work.

Below is a chart of the absorption rates of common food types assuming no delayed gastric emptying. Remember that the rate of this delay, if at all, is unpredictable, so it’s a big wildcard. For T1Ds who already have some degree of neuropathy, hypoglycemia-induced slowed gastric emptying shifts from accelerating (such as non-T1Ds) to slowing down by as much as 30–50%. So if you’re using any of the other foods listed in this table, and you’ve had T1D for >5 years or so, you may need to factor this delay into the absorption start and peak times!

Speed of Glucose Absorption

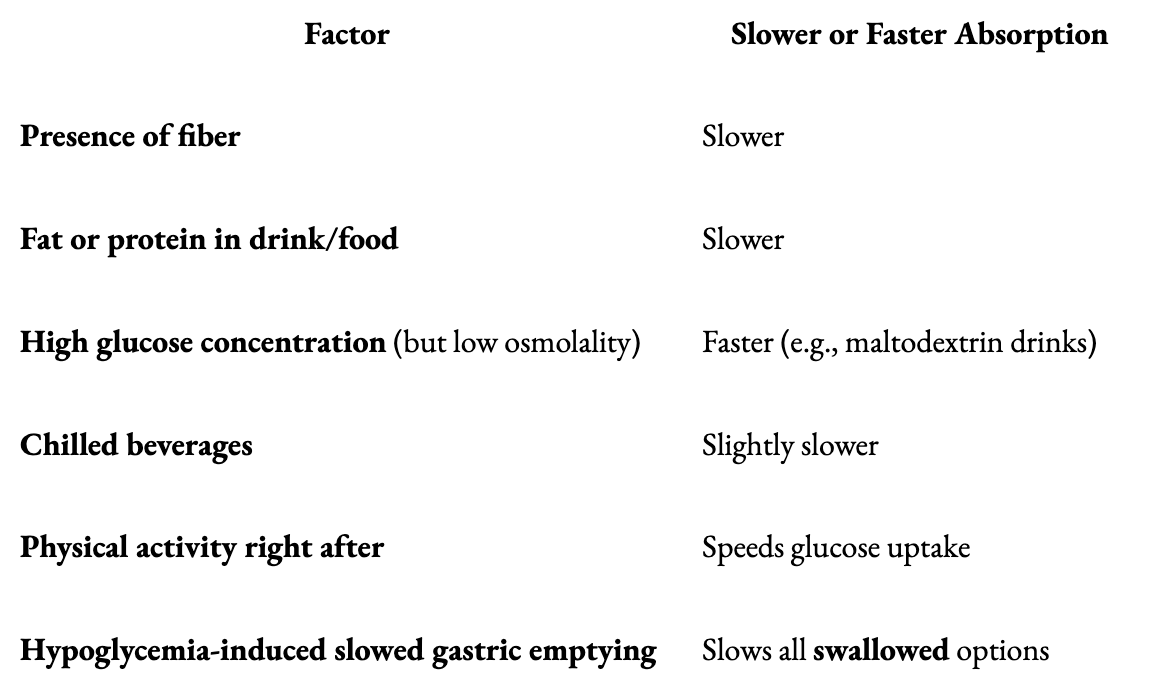

Note that Fructose-heavy fluids (like apple juice or applesauce) lag behind because fructose must be metabolized in the liver (and it takes a long time to get there), and viscous liquids take longer to get through the GI tract. With that in mind, the following table lists factors that can either slow down or speed up the gut’s absorption of foods.

Another factor is that a rapid drop in BG can cause panic-like adrenaline release, which might either speed up or shut down GI motility depending on balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. In other words, if you completely freak out and start to panic, it could speed up digestion. But that’s a big risk because it could also slow it down.

Let’s just say that if you’re in such a state where you have the presence of mind to “decide whether to panic,” then this might be a good time to add dextrose tabs or gels to your shopping cart.

Why not just use glucagon?

If a T1D is no longer able to care for themselves, then someone else has to intervene. Here is where the formal recommendation is to administer glucagon directly. Products that do this come either as an injection kit, or a much easier to administer nasal “spray.”

While they technically work, the problems with glucagon are numerous.

First, remember that glucagon is not glucose. It’s a hormone that signals the liver to produce glucose, and the source material that the liver uses is glycogen, a compact form of glucose that’s stored inside the liver. On average, a person normally has about 100g of glucose stored as glycogen.

So, in a pinch, one could use one of these glucagon kits, but here’s where the problems begin.

Unlike insulin, individual responsiveness to glucagon is highly variable and unpredictable.

This has been borne out in studies involving the administration of glucagon to patients where they are given up to 3 mg per dose. This very wide range of glucagon dosing is necessary because it’s not predictable whether any given individual will respond sufficiently to the lower end of this dosing range. To assure that someone recovers from hypoglycemia, the conservative approach is to administer that maximum amount. If it’s not enough, the patient may die.

Then there’s the effect of glucagon itself: Even under ideal conditions, it’s not that great. Once a bolus of glucagon is administered, blood glucose begins to rise in about 10–15 min, but the patient usually doesn’t become responsive for 20–30 minutes. In some cases (e.g., low liver glycogen, alcohol use, autonomic dysfunction), it can take between 60–90 minutes or more, according to the paper, “Nasal Glucagon: A Promising New Way to Treat Severe Hypoglycemia” – Diabetes Care (2019)

Because of the variability of responsiveness, glucagon kits have to contain one large, fixed dose, which assuredly overshoots for most people, triggering rebound hyperglycemia, nausea, and vomiting. Then the patient has to compensate with insulin, putting them on that roller coaster again, while still vomiting all over your rug.

Another complicating factor is whether the liver has sufficient glycogen storage. Remember a typical liver has roughly 100g of glycogen storage available, but there are conditions where someone might not have that much. One reason could be if someone is on a low-carb diet—such people are always at risk of having very low glycogen stores, putting them at even greater risk of hypoglycemia and difficulty recovering from it. This is why all major medical organizations advise AGAINST low-carb diets for T1Ds (though not necessarily T2Ds), including the American Medical Association, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and the American Heart Association. For more on this, see my article, The Paradox of Low-Carb Diets: A1c vs. Metabolic Health.

Administering glucagon to a patient with insufficient glycogen is like trying to jumpstart a car that has no gas at all.

The last nail in the coffin for external use of glucagon kits is that they are expensive (making them inaccessible to those without insurance) and they are perishable. Given the infrequency in which they are used, even if someone has a kit, it may have expired.

Occam’s Razor: The best solution is usually the simplest

Perhaps the biggest barrier to using glucagon—whether in a pump or a separate injectable—brings us all the back to the where we started: The rapid effect and simple administration of dextrose tablets or gels under the tongue is cheaper, easier, safer, faster, and does not carry any of the concerns raised by glucagon. Just squeeze dextrose gel into the buccal pouch or under the tongue of an unresponsive T1D, and make sure they’re facing down so they don’t choke. It's hard to beat this solution.

And yes, this method has been studied—a lot. In the research review paper titled, “First aid glucose administration routes for symptomatic hypoglycaemia”, a variety of techniques similar to the Dextrose method has been studied in multiple clinical trials, demonstrating meaningful rises in blood glucose up to 20 minutes later without carrying any risk, and can be easily administered by anyone.

In another study, “Sublingual sugar administration as an alternative to intravenous dextrose administration to correct hypoglycemia among children in the tropics,” published in Pediatrics in 2005, the authors describe a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy of sublingual sugar (dextrose) administration compared to oral and intravenous routes in moderately hypoglycemic children. From the paper: “...sublingual glucose led to a faster correction of hypoglycemia than oral syrup in children...”

The authors suggest that sublingual dextrose could serve as a practical alternative in settings where intravenous access is limited.

(Yes, the best option is having an IV hooked up to your veins so as to administer liquid dextrose. I had this done to me when I was 12 years old. I went from severely hypoglycemic to virtually normal in about 15 seconds. This is not something that can be administered in most situations though—you need to be in or near a hospital. I was lucky.)

So why isn’t this method of using Dextrose in the cheeks and under the tongue officially recommended?

Simply put: Medical authorities are reluctant to recommend interventions that have not been approved by the FDA. (Although, my endo told me about it in the 1990s, and I've been doing it ever since.)

So, why hasn’t the FDA approved such a technique?

Because no one has ever submitted a product or protocol.

So, why not submit a product or a protocol?

Economics. Given that a bottle of 50 dextrose tablets cost roughly $5-10, there’s no business model for anyone to go to the time and expense to solicit a product and protocol to the FDA.

Final Note

Speaking of Occam’s Razor, where the simplest solution is usually the right one, perhaps the best treatment for hypoglycemia is preventing it from happening in the first place: Watch your CGM frequently, and be proactive by consuming dextrose before your sugar drops. Those who say that I make it sound “too easy to be true”, I always respond with, “Yeah… But have you tried?” It’s actually not hard at all, once you decide to do it.

Case in point: The BG chart I showed earlier showed exactly that. I intervened with dextrose to bring my glucose levels up well before I went hypo. Here it is again:

Ok, 10pm, that’s easy. But, 1:30am? At night, I set my alarm for 80, so I can catch it and take the dextrose before I go hypo. Fortunately, the drift downward was slow enough, but there are occasions, where it drops faster. Such is life. But the point is, the more you watch your CGM, the more likely you can act ahead of time. And best of all, you start to notice patterns that you become familiar with.

Watching your CGM is the first of the four ‘very easy’ habits I describe in my article, Self-Identity and the Four Habits of Healthy T1Ds.

The only thing I haven’t been doing is keeping the glucose tabs in my mouth to absorb before swallowing. That makes sense.

I'm already using dextrose in my Rockets candy. (Called Smarties in the US.) Much cheaper than Dex4 tablets. One roll is 7g CHO. But I will try to hold it in my mouth. Thanks for the great tip.