The Best Way to Treat Hypoglycemia

Treating hypos incorrectly has both short term and long term consequences

To listen to the podcast edition of this article, click here.

Whenever I’m with a group of T1Ds, someone invariably brings out some kind of product to treat their low blood sugar—the point where glucose levels drop below 70 mg/dL, also known as hypoglycemia. Parents of their T1D children give them a juicebox, while adults might snack on an energy bar, apple sauce packets, yogurt, juice/soda or some other sugary drink.

While all of these elixirs will do the job (eventually) each has effects that may make them less effective than they should be, and worse, could cause undesirable side effects later, both short term and long term.

Because it’s nearly impossible to properly know (or even estimate) the exact amount of glucose needed for a hypo event, most people eat more than they need, which is understandable—hypoglycemia is akin to torture. Yet, over-compensation often leads to the dreaded glucose roller coaster: Sugars skyrocket too far, thereby requiring insulin to correct, which is also too much, and into the loop part of the roller coaster we go. The rest of the day (or night) is spent trying to return to homeostasis. This is the worst “experience” in T1D (apart from DKA, I suppose).

Some are so fearful of hypos that they just keep their sugars higher. Dangerously so. “Fear of hypoglycemia” (FOH) is such a serious phenomenon, it leads not just to poor control, it triggers psychological distress, and keeps people from exercising, perhaps the best and most important way to manage diabetes.

There’s quite a bit about hypoglycemia that could be addressed, but this article really narrows it down to one thing: the best way to treat it. But along the way, we also have to learn some physiological aspects about it, not just because it’ll help you better understand why the treatment works, but it will also unmask a lot of misunderstandings about hypos that may make you less afraid of it.

Let’s start with the basics.

Ye Olde Nervous System

Let’s return to that gathering I mentioned earlier, where T1Ds use different ways to treat their low glucose levels. The reason each of these choices—from juice boxes to energy bars—are not ideal for treating hypos is because of how these foods are processed in the gut. Even though people think they’re absorbing “fast” carbs, it turns out to be a lot more complicated than just that. So, let’s go into the gut.

Everything you eat goes through a process called gastric emptying, which is characterized by the rate at which the stomach delivers its contents to the small intestine, and how the body processes those contents. Let’s start with how things are supposed to work.

In non-T1Ds, when glucose levels drop too low, the sympathetic nervous system responds in two ways: First, it accelerates gastric emptying, facilitating rapid glucose absorption. So, if someone (say, an athlete) runs low on glucose, they can slam down an energy gel and all’s well. Keep this in mind, as it’s an important element that will come up later.

Secondly, the sympathetic nervous system signals alpha cells (that sit next to beta cells) to produce glucagon, a hormone that signals the liver to produce glucose (gluconeogenesis), which raises glucose levels. To prevent blood glucose levels from bouncing around, the body synchronizes its insulin and glucagon secretion to be in tight communication. This is why the alpha and beta cells are physically next to each other in the pancreas—they talk to each other.

This tight ecosystem of signaling is largely how a non-T1D body maintains glucose levels.

But in T1D, the beta cells are dead, so this communication is broken, and it leads to a cascade of problems that, over time, waterfall into a progressively difficult state of affairs.

Cascade of Problems: Neuropathy

I need to emphasize that this section describes the effects that happen very slowly over time. Many newly diagnosed T1Ds, especially children, do not experience much of what’s described here—but they will. One can delay this cascade with tighter glycemic control and—especially—exercise, which protects nerves (and other tissues) from assaults, but also aids in healing.

But, even in the best circumstances, higher glucose levels lead to neuropathy, particularly the sympathetic nervous system.

Digestion is governed by the sympathetic nervous system, which slows down gastric emptying in ways that are unpredictable and volatile, often without notice. When the condition surpasses a particular threshold, it’s classified as gastroparesis, a condition affects approximately 28% of T1Ds, according to the paper, Prevalence of delayed gastric emptying in diabetic patients.

While gastroparesis may only affect a smaller percentage of T1Ds, remember that the formal diagnosis is a threshold that misses a much larger percentage of T1Ds whose symptoms are more mild. Statistically, anyone that’s had T1D over 10 years already have some degree of it. Five years is common, but is highly dependent on not just glycemic control, but weight management and—again—exercise.

Making matters worse, gastric emptying can also be slowed by hypoglycemia. This is the biphasic nature of the intestine and the nerves that govern it—in non-T1Ds, hypoglycemia can increase gastric emptying, but when T1D sets in, the process can reverse, slowing down absorption. For T1Ds who already have some degree of neuropathy, hypoglycemia-induced slowed gastric emptying can be range from 30–50%.

Wait, there’s more! If your hypo-treatment elixir also includes any amount of fat or protein—such as protein bars or chocolate or, well, most anything—those ingredients will delay absorption even more than gastric emptying will (for reasons beyond the scope of this article). What’s more, proteins and fats will cause glucose levels to rise later, long after the sugars already had.

So, let’s quickly return to that gathering of T1Ds that are treating their hypos by eating candy, or apple sauce, or honey, or whatever they have around. The slowed gastric emptying allows some, but not all, of the carbs in. So, there’s a feeling of recovery, but the person is unaware that only a small portion of those carbs did the trick. The rest are still sitting in the intestine, waiting. And you know what comes next: the huge spike, and the roller coaster.

Let’s also not forget how the hypo happened in the first place: Misalignment of carbs and insulin dosing earlier.

As you’ve no doubt learned when you were diagnosed with T1D, you take insulin (or you rely on pumps to administer it) alongside food intake. Ideally, the two sync up and you’re fine (most of the time). Hence, children do exceptionally well, especially with automated insulin pumps that use algorithms that assume absorption of food and insulin are absorbed according to “textbook” patterns.

As time passes, glucose levels are just naturally higher. Worse, glucose levels bounce around on the glycemic roller coaster (a process called glycemic variability, or GV), the progression of neuropathy accelerates.

As time goes on and T1Ds begin to experience systemic volatility, the rate in which that food is absorbed becomes even more volatile, putting insulin dosing out of alignment with carb intake. And when that happens—even by a tiny amount, say, 30 minutes—you get the big crash: hypoglycemia.

Just because you’ve counted carbs (and told your insulin pump), it doesn’t mean that you know how much of those carbs have been absorbed, or when it might. You can’t know that. As time goes on, it becomes increasingly less predictable. If you use a T1D app that attempts to present how many carbs are “on board,” do not trust it. (The same is true of “insulin onboard”, or IOB, but for very different reasons that I’ll cover in another article.)

“Delayed gastric emptying” becomes a major, but ghostly factor in T1D management: It’s there, but it’s very hard to see. Shoving a lot of “fast carbs” into your gut is like filling up your car with gas, only to find that the fuel line isn’t letting the gas get into the engine.

The result: Hypos happen more frequently, are more severe, and are harder to treat.

As neuropathy further erodes, it leads to hypoglycemic unawareness because the nerves just aren’t there to make you aware that your glucose levels are low. People can be as low as 40 mg/dL and feel perfectly normal—until their car careens off the side of the road. Not so normal anymore.

Ironically, the horrible, horrible feeling from hypoglycemia is a sign that you still have function in your sympathetic nervous system, even though it may have some impairment. But if the fear of it causes you to keep your glucose levels dangerously high, that will actually bring further harm to your sympathetic nervous system.

This all brings us back to the best way to treat hypoglycemia in ways that get around all these problems.

The solution: Avoid the gut completely

When gastric emptying is slowed, the absorption of orally ingested carbohydrates is delayed, so the best thing to do is avoid the gut entirely. That’s right, you can use glucose tablets or gels composed of Dextrose and follow these simple steps:

Chew up some number of tablets (or squeeze gel under your tongue) and try not to swallow. (This part requires practice because you really want to swallow.)

Redirect the saliva-laden granules to your cheek pouches and under your tongue (oral mucosa).

Hold in place for at least 1–2 minutes—but longer, if you can—before swallowing.

How many grams you should consume varies—we’ll get to that shortly—but it’s important to understand how and why this process works, and why it helps avoid the other problems discussed till now.

There is a lot of vasculature in the oral mucosa, and since dextrose is a very small sugar molecule, it can be absorbed directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the gastrointestinal tract entirely.

This is as close as you can get to the timing of a non-diabetic glucose correction short of being hooked up to an IV and having dextrose manually administered.

And for clarity, “dextrose” is formally “glucose” (D-glucose), which is not the same as the kind of simple sugars that most people call “glucose”. It’s a word/phrasing thing that can confuse people.

Anyway, the primary benefits of using dextrose in the mouth include:

Bypassing your intestines assures that these carbs will be absorbed as quickly as feasible.

Dextrose is in and out of your system—fast. Once absorbed, you’re done. There’s no risk of extra carbs that will get absorbed later, leading to the roller coaster.

Speedier absorption makes it less likely that your counter-regulatory system kicks in (assuming it’s working). Hence, you’re less likely to get the roller coaster effect (or if you do, it’ll be much more mild).

Because tablets only contain 4g each, it’s harder to over-compensate by eating too much. This is good, because, more often than not, you don’t need as much as you think (though the panicky feeling doesn’t make you feel that way). The limited speed in which you can consume tablets (using this technique) helps limit over-compensating. Now, instead of ravenously wolfing down that box of girl scout cookies you’ve been eyeing, you’re being slowed down by a more direct and sensible method.

Note that “gel” versions of Dextrose are also available (e.g., “Insta-Glucose”), which make it easier to get under your tongue, but they generally come in larger tubes or packets (15-24g each), so it’s not easy to get a smaller dose if you want one (without losing accuracy). The tablets are ~4g each, so if you want accurate dosing at lower quantities, that may be a better option.

As for how much glucose you actually need, that’s tricky, but there are good ways to think about this, so let’s go there.

How much glucose do we need?

The following comes directly from my article, Why Controlling Glucose is so Tricky:

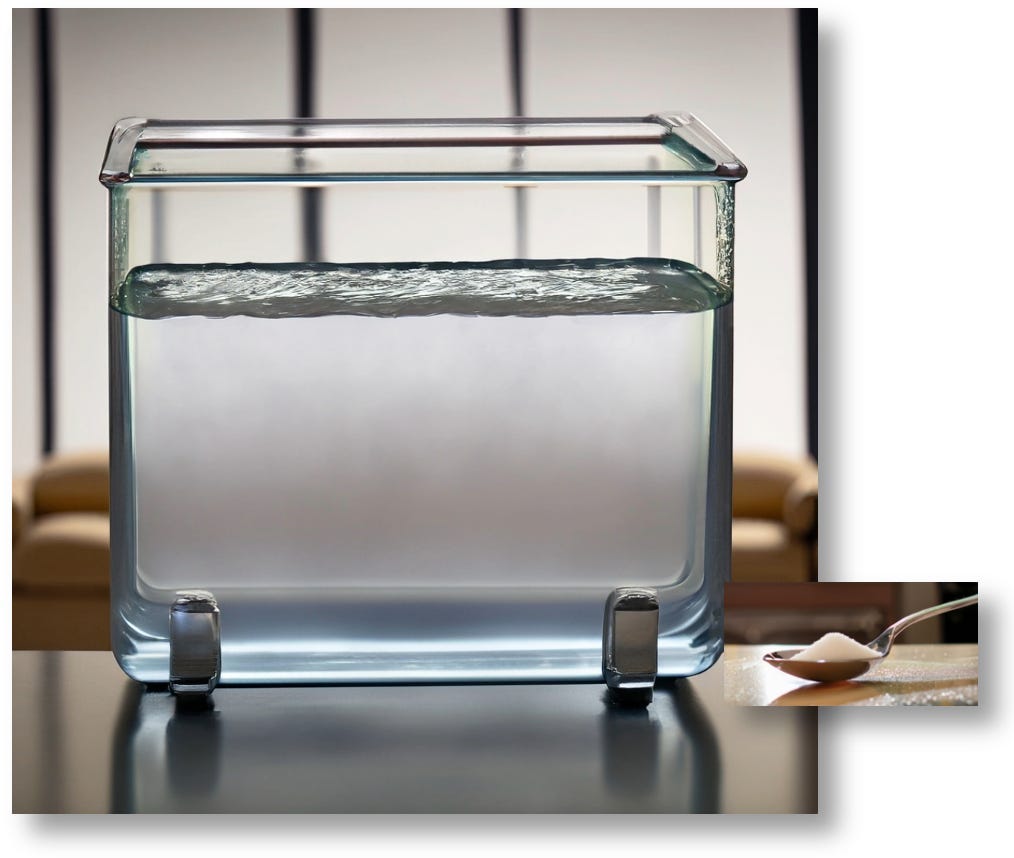

The average person has between four and five liters of blood, so a “normal” blood glucose level of 100 mg/dL means that a typical person has about one teaspoon of sugar throughout their entire bloodstream. That’s a whopping 4.2g of glucose. Here’s a visual representation, brought to you by AI.

As you can see, 4.2g of glucose is proportionally tiny to the total volume of fluid. If you were to add 2.1g of glucose—a half a teaspoon of sugar—the total glucose content of this beaker would grow to 140 mg/dL.

But as any diabetic can affirm, eating a half teaspoon of sugar isn’t going to raise glucose levels to 140. So, where is all that glucose going? The short answer is that it’s being shuttled out of the bloodstream and into different parts of the body, wherever it happens to be needed. To learn about that, read the article.

For purposes of this context—correcting for hypoglycemia—that glucose is going to your brain first, then to other essential organs.

To illustrate how I use Dextrose tabs in this way, see the following chart, where I consumed 4 tablets at 10pm, which brought my glucose levels up to 137 within 30 minutes. Then I took 2 tablets at 1:30am, raising my glucose to 111.

The first question you may be thinking is: “If Dextrose works within minutes, why did it take so long to rise from 95 to 137, and from 80 to 111?”

Remember, that’s how long it took before it hit its peak. It started up immediately. After that, the dextrose was filtering through my bloodstream and immediately getting shuttled to other parts of my body. This is why the 15g didn’t raise my BG much, much higher. It went up—and fast—but it was also being cleared from my bloodstream equally as fast. The dextrose most likely “peaked” 10m later, but the clearance was not far behind.

Note that the job of “clearing” glucose from the bloodstream is done by more than just insulin—many other factors in your body is clearing glucose. But in this case, for this event, insulin is indeed the primary clearing mechanism. We can see this by the dashed blue lines on the chart that revealed a steady, downward BG trend, due to having basal insulin on board, pushing my BG downward. Had I not had that much basal insulin at work, my glucose would have shot sky high into the 200s, probably right away. (But then, I wouldn’t have taken the dextrose.)

This leads to the second question: “Why is your basal insulin rate so high?”

The answer is, “It’s not anymore!”

No seriously: Years ago, I used a conventional basal rate set by my doc that I just did out of compliance. But I was getting a lot of lows at night, and just accepted it as the importance of assuring that I had “insulin onboard.”

The danger of too much basal insulin

As a general rule, yes, we need background (basal) insulin, but that doesn’t mean it’s ok to have too much of it. Tired of so many night time hypos, I refined my use of basal insulin by pulling back on it—significantly. Over the course of a couple weeks of experimentation of just watching my CGM more often and bolusing Humalog “as needed”, I eventually just stopped taking basal insulin altogether. It was surprisingly easier and less stressful than expected. In fact, knowing I don’t have all that insulin in me was a huge relief.

What I found as well was that the insulin absorption rate for both my basal and my Humalog were not as smooth and timed as expected. Absorption variability is a huge deal, and vastly underappreciated. For details, see my article, The Insulin Absorption Roller Coaster and What You Can Do. This is essential reading for all T1Ds.

You might wonder how I mange overnight insulin needs without basal insulin. The short answer is exercise. For more, see my article, The Paradox of Low-Carb Diets: A1c vs. Metabolic Health, where I how exercise taps into its glycogen stores during activity, but then those stores are replenished at night, while you sleep, by pulling glucose out of the bloodstream, without insulin mediation. I show charts about how this works. Any basal insulin would trigger hypoglycemia.

Without basal, I no longer have any fear of hypos, and any insulin absorption variability that may happen with Humalog is much easier to manage. It doesn’t mean hypos don’t happen. They are rare and quickly managed, and I don’t get on the roller coaster.

Taking less basal also helps by avoiding the overconsumption of carbs, and makes it much easier to exercise and eat more “flexibly.”

My experience is not unique to me, though it’s not common either. Learning this technique, while not that hard, is also not encouraged. It takes diligence to develop it.

But seriously backing off on the amount of basal insulin is very much advised, according to medical literature. According to the Lancet article, “Obesity in people living with type 1 diabetes,” hypoglycemia is often due to the discordance between the body’s needs in background insulin, versus what people are giving themselves. The more basal you have, the more likely you get hypos, and the unfortunate response is to consume more carbs than needed to correct it.

The June 2024 issue of Diabetes Care addresses this head on in an article titled, “Severe Hypoglycemia and Impaired Awareness of Hypoglycemia Persist in People With Type 1 Diabetes Despite Use of Diabetes Technology: Results From a Cross-sectional Survey.” The authors collected data from 2,074 T1Ds, half of whom used AID systems, whereas the rest were non-AID pump systems. Among all, “only 57.7% reported achieving glycemic targets of A1c <7%, but the number of severe hypoglycemic events from automated systems reached 16% for those using AID systems, versus 19% of non-AID pump users.”

Hyperinsulinemia—taking too much insulin—leads to increased body weight, which leads to obesity, insulin resistance, and more dramatic roller coaster swings. It’s a feedback loop. As the article points out, the rate of obesity among T1Ds reached 37% in 2023 compared to only 3.4% in 1986, and they attribute it to AID systems and pump usage increase that are indiscriminate on administering insulin.

For more on this, see my article, “Challenges Facing Automated Insulin Delivery Systems.”

Let’s move on to how dextrose compares with the more common and conventional way people raise their BGs.

Comparing dextrose with other carbs

If you do not have Dextrose when your sugar is low (I’m administering a stern look of disapproval), then you have no choice but to eat something else. And yes, for anything other than dextrose, you have to swallow it. The oral mucosa will not absorb any other form of sugar because those molecules are too big to pass through the membrane. So, trying to keep sugary soda or juice in your mouth will not work.

Below is a chart of the absorption rates of common food types assuming no delayed gastric emptying. Remember that the rate of this delay, if at all, is unpredictable, so it’s a big wildcard. For T1Ds who already have some degree of neuropathy, hypoglycemia-induced slowed gastric emptying shifts from accelerating (such as non-T1Ds) to slowing down by as much as 30–50%. So if you’re using any of the other foods listed in this table, and you’ve had T1D for >5 years or so, you may need to factor this delay into the absorption start and peak times!

Speed of Glucose Absorption

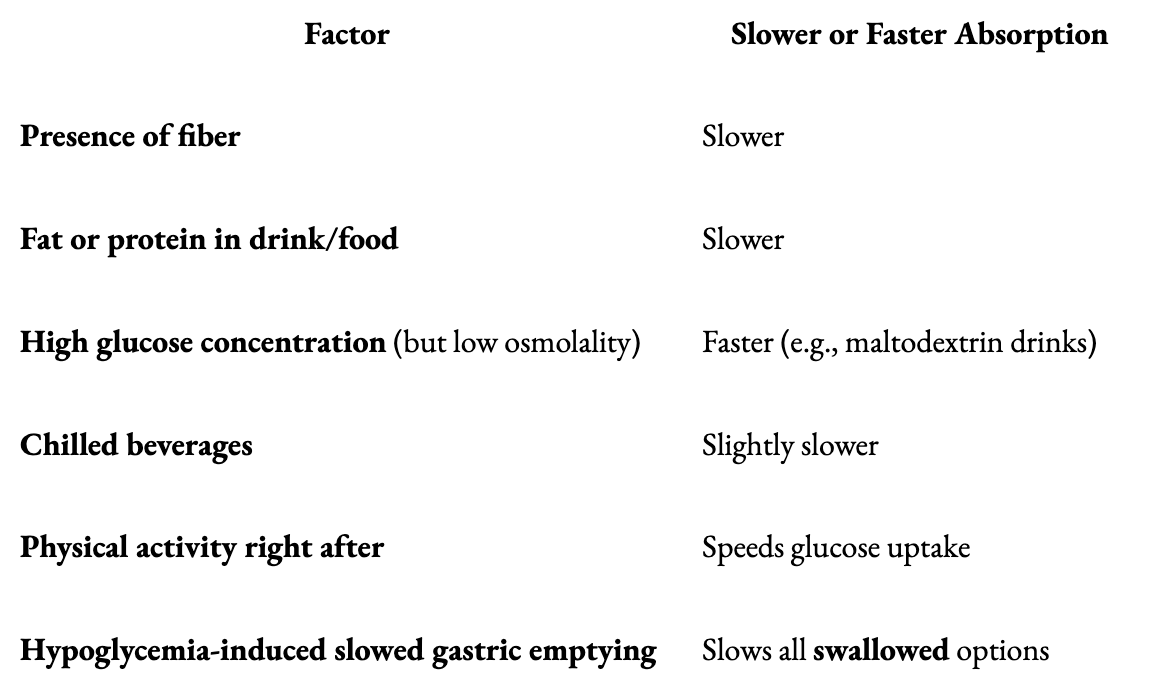

Note that Fructose-heavy fluids (like apple juice or applesauce) lag behind because fructose must be metabolized in the liver (and it takes a long time to get there), and viscous liquids take longer to get through the GI tract. With that in mind, the following table lists factors that can either slow down or speed up the gut’s absorption of foods.

Another factor is that a rapid drop in BG can cause panic-like adrenaline release, which might either speed up or shut down GI motility depending on balance between sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. In other words, if you completely freak out and start to panic, it could speed up digestion. But that’s a big risk because it could also slow it down.

Let’s just say that if you’re in such a state where you have the presence of mind to “decide whether to panic,” then this might be a good time to add dextrose tabs or gels to your shopping cart.

Why not just use glucagon?

If a T1D is no longer able to care for themselves, then someone else has to intervene. Here is where the formal recommendation is to administer glucagon directly. Products that do this come either as an injection kit, or a much easier to administer nasal “spray.”

While they technically work, the problems with glucagon are numerous.

First, remember that glucagon is not glucose. It’s a hormone that signals the liver to produce glucose, and the source material that the liver uses is glycogen, a compact form of glucose that’s stored inside the liver. On average, a person normally has about 100g of glucose stored as glycogen.

So, in a pinch, one could use one of these glucagon kits, but here’s where the problems begin.

Unlike insulin, individual responsiveness to glucagon is highly variable and unpredictable.

This has been borne out in studies involving the administration of glucagon to patients where they are given up to 3 mg per dose. This very wide range of glucagon dosing is necessary because it’s not predictable whether any given individual will respond sufficiently to the lower end of this dosing range. To assure that someone recovers from hypoglycemia, the conservative approach is to administer that maximum amount. If it’s not enough, the patient may die.

Then there’s the effect of glucagon itself: Even under ideal conditions, it’s not that great. Once a bolus of glucagon is administered, blood glucose begins to rise in about 10–15 min, but the patient usually doesn’t become responsive for 20–30 minutes. In some cases (e.g., low liver glycogen, alcohol use, autonomic dysfunction), it can take between 60–90 minutes or more, according to the paper, “Nasal Glucagon: A Promising New Way to Treat Severe Hypoglycemia” – Diabetes Care (2019)

Because of the variability of responsiveness, glucagon kits have to contain one large, fixed dose, which assuredly overshoots for most people, triggering rebound hyperglycemia, nausea, and vomiting. Then the patient has to compensate with insulin, putting them on that roller coaster again, while still vomiting all over your rug.

Another complicating factor is whether the liver has sufficient glycogen storage. Remember a typical liver has roughly 100g of glycogen storage available, but there are conditions where someone might not have that much. One reason could be if someone is on a low-carb diet—such people are always at risk of having very low glycogen stores, putting them at even greater risk of hypoglycemia and difficulty recovering from it. This is why all major medical organizations advise AGAINST low-carb diets for T1Ds (though not necessarily T2Ds), including the American Medical Association, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and the American Heart Association. For more on this, see my article, The Paradox of Low-Carb Diets: A1c vs. Metabolic Health.

Administering glucagon to a patient with insufficient glycogen is like trying to jumpstart a car that has no gas at all.

The last nail in the coffin for external use of glucagon kits is that they are expensive (making them inaccessible to those without insurance) and they are perishable. Given the infrequency in which they are used, even if someone has a kit, it may have expired.

Occam’s Razor: The best solution is usually the simplest

Perhaps the biggest barrier to using glucagon—whether in a pump or a separate injectable—brings us all the back to the where we started: The rapid effect and simple administration of dextrose tablets or gels under the tongue is cheaper, easier, safer, faster, and does not carry any of the concerns raised by glucagon. Just squeeze dextrose gel into the buccal pouch or under the tongue of an unresponsive T1D, and make sure they’re facing down so they don’t choke. It's hard to beat this solution.

And yes, this method has been studied—a lot. In the research review paper titled, “First aid glucose administration routes for symptomatic hypoglycaemia”, a variety of techniques similar to the Dextrose method has been studied in multiple clinical trials, demonstrating meaningful rises in blood glucose up to 20 minutes later without carrying any risk, and can be easily administered by anyone.

In another study, “Sublingual sugar administration as an alternative to intravenous dextrose administration to correct hypoglycemia among children in the tropics,” published in Pediatrics in 2005, the authors describe a randomized clinical trial that evaluated the efficacy of sublingual sugar (dextrose) administration compared to oral and intravenous routes in moderately hypoglycemic children. From the paper: “...sublingual glucose led to a faster correction of hypoglycemia than oral syrup in children...”

The authors suggest that sublingual dextrose could serve as a practical alternative in settings where intravenous access is limited.

(Yes, the best option is having an IV hooked up to your veins so as to administer liquid dextrose. I had this done to me when I was 12 years old. I went from severely hypoglycemic to virtually normal in about 15 seconds. This is not something that can be administered in most situations though—you need to be in or near a hospital. I was lucky.)

So why isn’t this method of using Dextrose in the cheeks and under the tongue officially recommended?

Simply put: Medical authorities are reluctant to recommend interventions that have not been approved by the FDA. (Although, my endo told me about it in the 1990s, and I've been doing it ever since.)

So, why hasn’t the FDA approved such a technique?

Because no one has ever submitted a product or protocol.

So, why not submit a product or a protocol?

Economics. Given that a bottle of 50 dextrose tablets cost roughly $5-10, there’s no business model for anyone to go to the time and expense to solicit a product and protocol to the FDA.

Final Note

Speaking of Occam’s Razor, where the simplest solution is usually the right one, perhaps the best treatment for hypoglycemia is preventing it from happening in the first place: Watch your CGM frequently, and be proactive by consuming dextrose before your sugar drops. Those who say that I make it sound “too easy to be true”, I always respond with, “Yeah… But have you tried?” It’s actually not hard at all, once you decide to do it.

Case in point: The BG chart I showed earlier showed exactly that. I intervened with dextrose to bring my glucose levels up well before I went hypo. Here it is again:

Ok, 10pm, that’s easy. But, 1:30am? At night, I set my alarm for 80, so I can catch it and take the dextrose before I go hypo. Fortunately, the drift downward was slow enough, but there are occasions, where it drops faster. Such is life. But the point is, the more you watch your CGM, the more likely you can act ahead of time. And best of all, you start to notice patterns that you become familiar with.

Watching your CGM is the first of the four ‘very easy’ habits I describe in my article, Self-Identity and the Four Habits of Healthy T1Ds.

The only thing I haven’t been doing is keeping the glucose tabs in my mouth to absorb before swallowing. That makes sense.

I'm already using dextrose in my Rockets candy. (Called Smarties in the US.) Much cheaper than Dex4 tablets. One roll is 7g CHO. But I will try to hold it in my mouth. Thanks for the great tip.