Low-carb Diets Revisited

Food for thought on a controversial topic

If you’ve been following along in the last several posts, I’ve been leading along a trail discussing the problem with overbasalization—a term the ADA uses to describe the overly aggressive dosing protocols for basal insulin—which has led to a rise in obesity and other metabolic dysfunctions among T1Ds.

My first article laid the groundwork for how and why the ADA now recognizes this problem, and it lists decades of medical literature that highlights health problems that the ADA recognizes has been caused by overbasalization.

The key among all these articles is “physiological needs” or “metabolic needs”.

And that brings us to diets. Because your food choices affect your dosing decisions—bolus and basal alike—I’ve decided to completely update one of my older articles on the topic, which helps set the stage for the forthcoming articles that will follow in this series.

I invite you to read (or re-read) The Paradox of Low-Carb Diets: A1c vs. Metabolic Health.

To prepare you, this is a very long article. It’s essentially two articles—diet and exercise—that I will eventually split into two. If you’d prefer to listen to a podcast style explainer, you can download it here.

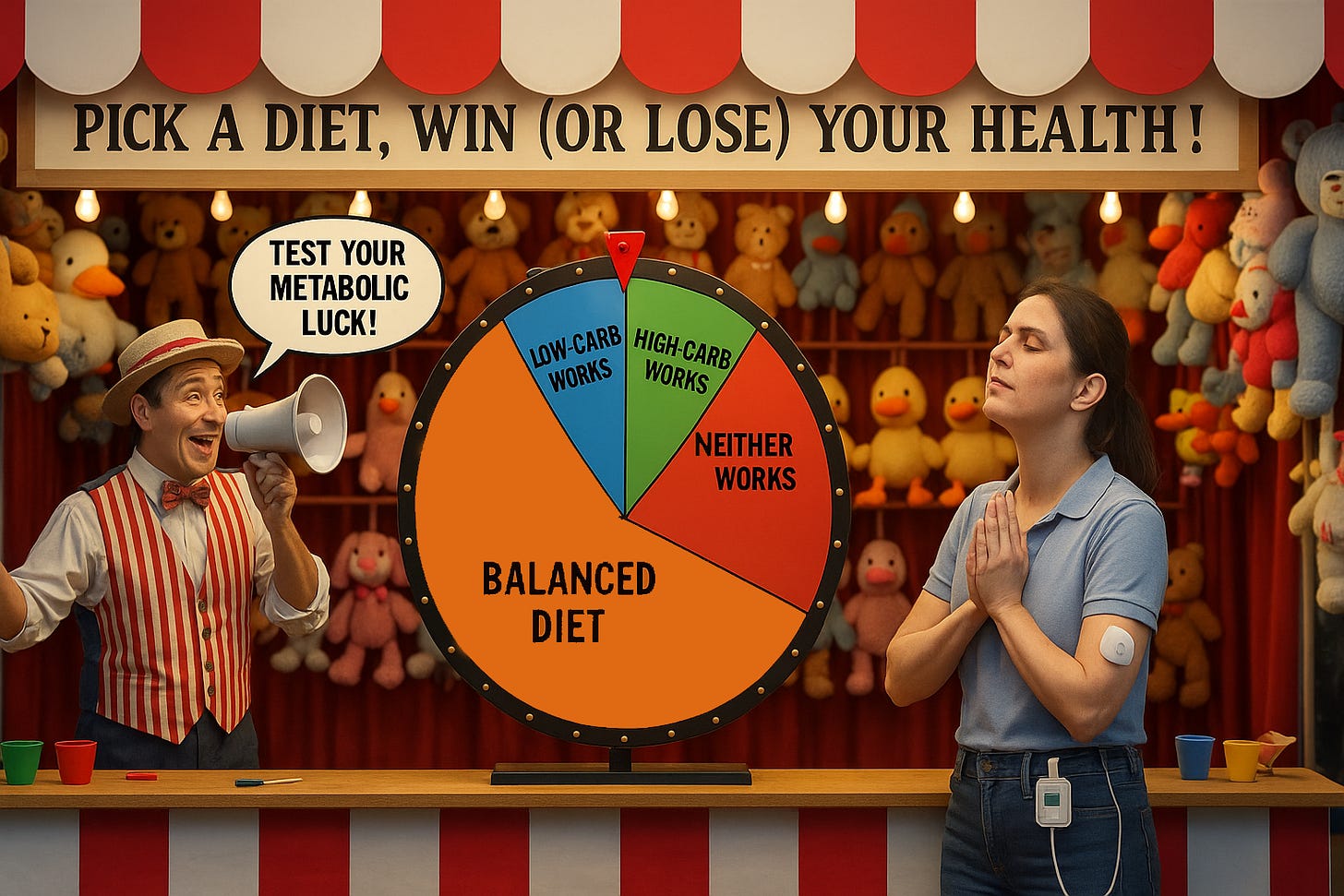

The article explores the full spectrum of carbohydrate approaches, from Dr. Bernstein's ultra-restrictive 30g/day diet, all the way to the other extreme, the "Mastering Diabetes" movement's high-carb, low-fat approach where practitioners consume 600-700g of carbs daily yet maintain excellent glucose control.

In the middle are guidelines that set carb ratios by weight and exercise levels.

A key finding in recent literature is that genetics guides what is most appropriate for each of us. Nutrigenetics studies how a person's genes affect their response to nutrients in ways that lead to different metabolic responses to carbohydrates. One can have genes that metabolize glucose, fats, and proteins more efficiently than others, whereas these same diets can present higher risk for others.

In fact, there are many fascinating genetic anomalies found throughout the population. For example, 15% of obese individuals are "metabolically healthy", despite the fact that they vastly exceed weight norms. Imagine these people saying that they eat anything and everything, and they’re perfectly healthy, so you should try it too!

Obviously, that would be preposterous. And so it is with any genetic outlier group who happen to succeed quite well at their diet. They may do well, but fail to see that they are outliers.

Ultimately, the article argues that metabolic fitness—not just glucose control—should be the primary health goal for T1Ds. Since the level of exercise required to build and strengthen mitochondria demands direct access to glucose, this may conflict with ultra-low-carb approaches. And vice-versa: Over-excessive carb intake just for the sake of extreme exercise can impede metabolic health as well.

I hope you find the material enlightening and, if nothing else, good food for thought.

You left out an important "need" which is the psychological piece that goes way beyond any physiological "requirement" for carbohydrate (there is none, by the way).

Many people are so intensely carb-addicted that the mere thought of removing sugars (including sugary fruits) and grains is anathema to them. Carb addiction is real, no different than opioids in terms of its effect on the brain (although obviously not as dire in outcomes).

Americans' diets are heavier in carbs than any time in history. Before 1900, Americans ate more protein and fat, with carbs coming mostly from whole foods like corn, potatoes, seasonal fruits, and some grains. ALso remember that fruit then hadn't been hybridized to be as sweet as candy so that corn and those peaches weren't anything like the versions we eat today. Back then, per-capita sugar consumption was around 10–15 pounds per year (in 1800).

By the middle of the 20th century, processed flour and sugar had become widespread, but home cooking still emphasized meat, eggs, vegetables, and dairy. By 1970, sugar intake had climbed to about 120 pounds per year per person.

Today the average American consumes over 300 grams of carbs per day, with around 60% of calories from carbs, much of it ultra-processed. Annual sugar intake per person now hovers around 150 pounds, and that's not accounting for the large amounts of refined flour and industrial snacks.

Processed food as the main source of our carb intake: white bread, pasta, crackers, breakfast cereals, most of which have been stripped of fiber and nutrients, are digested quickly, and cause blood sugar spikes even in non-diabetic people. There there's soda, sweetened coffee drinks, sports drinks, candy, pastries with enough preservatives to remain edible for a decade. Liquid sugar is especially problematic because it bypasses satiety.

Carb addiction is a dopamine response: Processed carbs, especially sugar, activate reward pathways in the brain similar to addictive substances.

Bottom line, Americans are eating more carbs, mostly in the form of refined sugar and flour—than at any point in history. Whole-food carbs (vegetables, berries, beans, tubers) aren’t the problem; it’s the industrialized, refined carbs that now make up the bulk of the diet, creating something very close to a national carb addiction.

Even when faced with the possibility of normalizing blood sugars and reversing Type 2 diabetes, we are unable or unwilling to part with our Twinkies. And don't get me started on parents of kids with Type 1 who are so carb addicted they're willing to risk their child's health. That's another comment altogether.

I appreciate these posts. I don't personally follow low-fat or low-carb diets for my T1D, but nevertheless I'm curious to learn more about them.

Cyrus Khambatta et al. has conducted a randomized trial to test his hypothesis that low-fat diet will reduce insulin doses in type 1 diabetics. Indeed, there was a reduction in insulin dose, but the participants also lost weight. Body weight clearly impacts insulin sensitivity, so it's difficult to tease apart the effects of weight loss versus diet.

The cross-sectional TypeOneGrit survey published in Pediatrics is also fascinating. The participants have achieved impressive A1C values, but the cross-sectional design is not suitable for interpreting the causes. The authors show that the CGM mean was 104 mg/dl, and standard deviation was 28 mg/dl. With some liberal statistical assumptions we can estimate an average of ~11% time in hypoglycemia. While I appreciate the achievements of the group, some of the participants seem to target excessively low blood glucose targets.

The supplementary file of the TypeOneGrit survey also shows that only minority of the study participants had low C-peptide. That supports your point about heterogeneous sample which includes LADA diabetics and others. Many T1D publications have a strict exclusion criteria where the participants are required to have zero C-peptide.