The running joke in the T1D community is that a “cure” is only five years away… and always will be.

I first heard this when I was diagnosed in 1973, and T1Ds at that time told me they’d been told that years earlier. Even today, T1Ds muse about it.

Nevertheless, one wonders that if a cure were to come, what would it look like?

Let’s start with a truism: Autoimmune diseases are caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors, but in the end, it’s our DNA that dictates how our immune system reacts to those environmental triggers that causes antibodies to attack beta cells. Changing our DNA so as to rewrite the script that constructs our immune system is the one true “cure” for T1D. But there are so many hurdles, caveats and risks to genetic engineering, there has never been a cure for any autoimmune disease.

For this reason alone, a cure in the purest definition is not on the horizon. Instead, we can look for a “functional cure,” where an intervention (or set thereof) allows for someone to stop taking insulin.

So, is that only five years away?

Well, it depends on what you’re willing or able to tolerate in exchange for being insulin free. There may be toxicity. There may be ongoing maintenance therapies. There may be other restrictions. It could be really expensive. And you might not necessarily achieve “healthy” glycemic control. So, it’s hard to say when—or even what—a pragmatic “functional cure” may look like.

The American journalist, author and socio-political critic of the early 20th century, H. L. Mencken famously said, “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.” T1D is exceedingly complex, so do not expect there to be easy, simple solutions.

What’s important is changing our perception of what a cure is, or that it’s even an endpoint at all. There will not be a dramatic, obvious event, with champagne bottles popping and insulin pumps thrown into electronics recycling bins. Instead, it’ll be a subtle, gradual, quiet realization. As researchers find “curative-like” therapies that trend iteratively closer to insulin independence, each comes with caveats. Whether to adopt one of them will come with trade-offs—choosing the lesser of two evils. Should you use the latest therapy? Or wait until there are improvements?

Keep all this in mind as we review the various areas that scientists are pursuing.

The Immune System and T1D

All the various approaches towards freeing T1Ds of taking insulin are centered around the immune system, which produces the antibodies that attack beta cells.

To understand these approaches, think of antibodies like the police in a city, whose job it is to take out the bad guys (viruses). In the city of T1D, some cops mistakenly target the good guys—the beta cells that make insulin—because they look similar to the bad guys. Or, they might attack the good guys' factories, thinking they're harboring bad guys. Here are some ways to address this "confused cop" problem:

Suspend the police force: This is like using immunosuppressant drugs to slow down the immune system. The problem is, the real bad guys will run rampant.

Wall off the good guys: This is like encapsulating the beta cells, protecting them from the immune system. But things need to get in and out of that enclosure—not easy.

Send in a negotiator: This is like using monoclonal antibodies to calm down the attacking immune cells.

Replace the police force: This is like CAR T-cell therapy, resetting the immune system.

Now that you have a visual, let’s review current progress to see how these approaches are working out.

Suspending the police force: Immunosuppressants

Immunosuppressant drugs slow down or suppress the immune system, akin to suspending the police force. This has been used successfully in a number of therapies, most notably organ transplantation, certain cancers, severe allergic reactions, multiple sclerosis, and more. The problem is, such drugs carry risks, primarily an increased susceptibility to infections, and as such, they are mostly used under urgent or temporary conditions, where someone’s life is at risk, or in order for other therapies to take effect.

A slightly more targeted method of immunosuppression was used in 2000 to implant new islets into T1Ds by Dr. James Shapiro and his team at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, in what is called, The Edmonton Protocol. It was considered the first successful islet transplantation, and seven patients were able to achieve 100% insulin independence after an average of 12 months. Because their A1c’s dropped from 9.5% to 5.8%, hopeful T1Ds were abuzz that a cure will only be—you guessed it—five years away.

Unfortunately, duration of insulin independence varied significantly, and the immune system eventually figured out a way around the immunosuppressants, which themselves were causing increased risks of infections and other problems.

For these reasons, the use of widespread immunosuppressants is not considered viable as part of a cure. But we did make an important discovery: transplanted cells can function, opening the door to new sources of money and people that can take things to the next level.

But it’s critical to note that the cells were entire islets of Langerhans, not just beta cells, and those islets came from donors, an expensive and non-scalable source.

Since then, research into stem-cell therapy has made it possible to mass produce beta cells at low cost. While this is good, beta cells will not function as well when they’re alone as they do when they’re inside entire islets of Langerhans, which contain other cells critical to glycemic regulation: alpha cells (which produce glucagon), delta cells (which produce somatostatin), delta, gamma and sigma cells. These are not just important for glycemic control, but if they’re not there, or they dysfunction, it can lead to particularly bad forms of T2D.

Hence, the trade-off: Either use complete islets that are hard and expensive to harvest, or use easily and inexpensively produced stem cell-derived beta cells.

Either way, the immune system is an issue, so the next idea is to just wall off the cells from the entire immune system rather than try to suppress it.

Encapsulation: Separating the good guys from all cops

Encapsulating either entire islets or just the beta cells is one way to evade the immune system. Here, the cells are held in a semipermeable membrane that has pores small enough to keep out immune cells and antibodies (which are relatively large), but large enough to allow smaller molecules like glucose, oxygen, and nutrients to pass through. Insulin is very small, so it can diffuse out of the membrane and into the bloodstream.

Companies using this approach include Semma Therapeutics (acquired by Vertex), ViaCyte, Sigilon Therapeutics, EnCapsule Therapeutics, and academic research institutions (Harvard, MIT, the University of California, and many others).

One of the first challenges of encapsulation is fibrosis. The body's natural response to any foreign object, including the membrane, is to try and wall it off by depositing collagen and other extracellular matrix components, forming a fibrous capsule. This effective barrier can pretty much shut down the whole operation. Can this process be stopped or slowed down, at least sufficiently to “replace” the encapsulated device if and when necessary? They’re working on that.

Another challenge is finding materials that are biocompatible (don't trigger an adverse reaction) and maintain the desired pore size over long periods. While the membrane protects the cells from direct immune attack, there can still be an inflammatory response in the surrounding tissue. This inflammation, even if not directly targeting the cells, can contribute to fibrosis and affect cell function.

A major stumbling block is oxygen supply because beta cells have a high oxygen demand, and getting enough oxygen to them within the capsule can be challenging due to diffusion limitations and fibrosis. Oxygen deficiency can lead to cell death and graft failure, which is another problem that we’ll raise again in a moment. Just because the pore sizes may be large enough doesn’t mean enough oxygen can get in. They’re working on that too.

Then there’s the location of the device. In non-diabetics, digested food enters the portal vein that leads directly to beta cells (and other cells in the pancreas), where direct, instant access to the primary blood conduit makes tight glycemic control possible.

But if the location of the encapsulation device is elsewhere—such as interstitial tissue, where most trials are currently testing it—access to blood is less efficient (and possibly faces other physical barriers), compromising the accuracy of blood glucose levels, as well as the absorption of insulin, not to mention insufficient access to oxygen.

Placing the device deeper inside the body, such as the liver or anywhere near the portal vein limits access to the device for periodic servicing. One example being the need to replenish beta cells that die off, either by natural turnover, or because they’ve been destroyed by insufficient oxygen.

Finally, there’s the difference between using stem cell-derived beta cells or entire islets. Currently, the majority of studies are involving entire islets for the reasons cited earlier: Only full, complete islets are able to achieve ideal glycemic control. Even though it’s already been established that donor-obtained islets is not a long-term solution, conducting trials that use both islets and only stem cell-derived beta cells can quantify exactly the differences in performance between the two approaches.

And clinical trials are bearing this out. In the paper published in Nature in 2024, Encapsulated stem cell–derived β cells exert glucose control in patients with type 1 diabetes, the patient that achieved the best results saw an improved time-in-range from 55% to 85% at the twelfth month, and an A1c slightly under 7%. Not exactly ideal. Moreover, this can be achieved using current T1D treatment, which is less expensive, less risky, less invasive, and “easier.”

Addressing these significant challenges may take another five years or so before they can say definitively whether they’ll need yet another five more years after that.

But none of this has not been for naught. These real-world conditions contribute greatly to what the next phase of development can bring. In the meantime, let’s move onto another approach: trying to “modulate” the immune system.

Monoclonal antibodies: Negotiating with the immune system

Rather than suspending the police force or walling them off, another approach is to negotiate with the bad cops to get them to tame down their bad behavior. This technique involves monoclonal antibodies, which are found in drugs like Humira (Rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, etc.), Herceptin (breast cancer), and Avastin (colorectal, lung, and kidney cancer), among others.

These drugs are highly effective at giving relief to patients, but these are not cures by any stretch. The effects of the disease are just less severe. It may be that this approach could be effective at giving beta cells a chance to survive a tad longer, which may aid in the encapsulation method or others.

Or, it might also be used as a direct therapy as well.

A recent monoclonal antibody drug called Teplizumab (Tzield) is an example. In a landmark clinical trial, Teplizumab in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: An Updated Review, the drug showed that it can delay the progression to stage 3 T1D, the point where daily insulin injections become necessary, by a median of three years, marking a significant advancement in T1D treatment.

While the initial 14-day course of Teplizumab has shown benefits, researchers want to determine if extending the treatment or using different dosing schedules can provide more durable and long-lasting effects than just the median three years currently seen.

As with all things involving the immune system, we cannot forget that it adapts. All patients using Tzield eventually got T1D because the immune system was relentless in working around the drug by adapting (or “mutating”) its chemical composition. Unexpectedly, those adaptations may have also led to a more worrying consequence: an increased risk of inducing other autoimmune diseases as well as T1D.

An article published in Clinical Diabetes, called, Teplizumab: Is It a Milestone for Type 1 Diabetes or a Risk Factor for Other Autoimmune Diseases in the Long Term?, the lead investigator for a clinical trial that involved Teplizumab explained how the very mechanisms that can cause a delay in the onset of T1D (by inhibiting the T-cells that attack the beta cells), might be inadvertently putting these patients at greater risk:

“We evaluated the relationship between the duration of the partial clinical remission (PCR), or ‘honeymoon’ phase, and the coexistence of other autoimmune diseases with type 1 diabetes. Our results showed that, as the duration of PCR increases, there are more cases of other type 1 T helper (Th1) cell–mediated autoimmune diseases associated with diabetes. In our study, patients who experienced >297 days of PCR seemed to be at greater risk of developing other autoimmune diseases associated with diabetes compared with those with <297 days of PCR.”

To be clear, new antibodies are not being created, but rather, existing antibodies are mutating, consequently affecting other cells.

Since the next round of Teplizumab trials aims to extend the period in which patients receive the drug, researchers are keeping an eye on whether that extended period may even further increase the risk of other autoimmune diseases. If so, we may add yet another five years for them to figure a way around this problem.

In the meantime, let’s move on to a different way to deal with the immune system: Reset it.

Turning the immune system against itself

CAR-T-cell therapy is fast getting the attention among researchers. Originally developed as a way to kill malignant cells in blood cancer, CAR-T cells are now being used to see whether they can kill specific white blood cells, called B cells, that go haywire with certain autoimmune diseases. In other words, it’s a way of turning the immune system against itself.

The “CAR” stands for Chimeric Antigen Receptor. Historically, the goal of this therapy has not been to kill the B cells that make antibodies, but rather to modulate them using regulatory CAR T cells, or Tregs. In fact, other immune cells are also targets for this form of modulation, leading to a suppression of their attack. This is the primary focus for T1D currently, and current trials are showing promise in the reduction of autoantibodies.

In the article, Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-Based Cell Therapy for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM); Current Progress and Future Approaches, the literature review cites several preclinical studies that demonstrated that directing Tregs toward the pancreatic beta cells may prevent diabetes onset and progression in diabetic mice models.

Yay mice. They get cured constantly.

Humans are different, but it’s still promising. Perhaps this could be used alongside other therapies that involve placing beta cells or islets inside the body.

But that’s not the only use of CAR-T-cell therapy; there’s been a new development that has not only been surprising, but shows greater potential than expected.

The story begins with a 20-year-old woman suffering from uncontrolled lupus, an autoimmune disease that can affect any or all organs in the body. In a story published in The Atlantic titled, A ‘Crazy’ Idea for Treating Autoimmune Diseases Might Actually Work, the woman’s kidneys, heart, and lungs were all failing, due to the autoimmunity from lupus. She could walk only 30 feet by herself. After the CAR-T-cell therapy, according to the article, “the woman now runs five times a week. She’s gone back to school and is considering studying for a master’s in immunology.”

The article cites studies showing that “more than 40 people with lupus worldwide have now undergone CAR-T-cell therapy, and most have gone into drug-free remission. CAR-T has already been used experimentally to treat patients with other autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis, myositis, and myasthenia gravis.”

If that was all to the story, it would seem the treatment could be available in about five years.

Oh, wait. There’s that old nemesis again: our DNA. CAR-T cells cannot erase the genetic predisposition written into the DNA of the B cells that make the antibodies, so CAR-T cells have to be individually engineered on a per-person basis using the genetic material of their B cells, which costs about $500,000. Patients also need chemotherapy to kill all existing T cells to make room for CAR-T, which is a difficult procedure and highly risky. And again, not enough time has passed to know whether the immune system will eventually catch up due to its programming by DNA. This procedure is not one that would be viable to do repeatedly.

Better add another five years or so to figure this out.

Once again, this was not for naught. A huge amount of new information was gleaned, giving rise to new areas of research to streamline the process, potentially making it scalable, or potentially in combination with other methods.

Summary

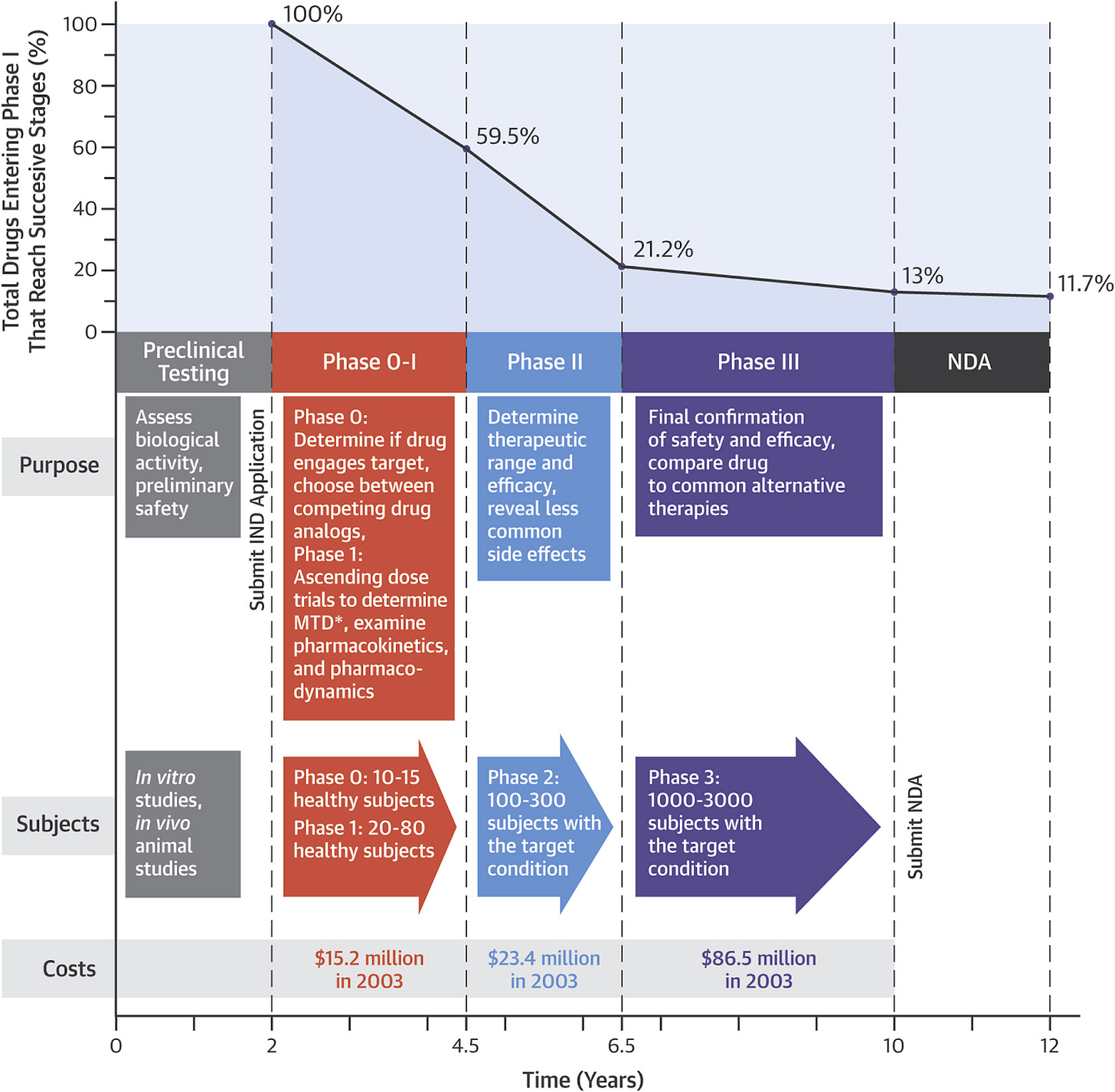

As stated in the beginning, expectations should be set about what a “cure” actually entails, and the iterative nature in which it is likely to evolve. Below is a chart from this article by Peter Attia, which explains the drug development process, its stages, the timelines, and the costs.

If there were a cure for T1D that we might see ten years from now, we’d see that drug being discussed right now in medical literature, with phase 0-1 trials showing some T1Ds being totally insulin independent.

Instead, we’re seeing the kind of iterative developments discussed in this article like Teplizumab and the challenges facing them moving forward. Suffice to say, nothing is on the horizon that leads to full insulin independence, at the same time, these drugs show progress, and that leads to future innovations and developments. True, only 11.7% of drugs typically see a commercial release, but it’s also the case that 90% of those drugs led to other science discovering that lead to other innovations that move us all forward. We wouldn’t have any of the T1D technologies we use today were it not for many failed attempts decades ago.

For today, this is how I think about it: If we ever reach a point where we no longer have to take insulin without risk of toxicity or any other side effects—to live a “normal life”—that’s not the end, but the beginning.

Glycemic control is hard, even among non-diabetics, where the rise of T2D in the US is skyrocketing, with an estimated ¾ of Americans—over 200 million—either have T2D, or are “pre-diabetic,” or suffer some other metabolic disorder. T1Ds are not in some other category. We have the same susceptibility to these disorders—if not more so—accounting for the rapid rise of “double diabetes.”

I say this not to end on a sour note, but to remind T1Ds that the best way to prepare for a cure, whatever form it might take, is to adopt habits that make living with T1D today much healthier, and, shockingly, easier. In my article, “Self-Identity and the Four Habits of Healthy T1Ds,” I explain how four habits—watching CGM patterns, intervening with appropriate counter-responses, watching food intake, and exercising—are the foundational behaviors for glycemic control. I end with this philosophical meditation:

If a “cure” were to ever materialize, I would probably still do all my habits, including wearing a CGM, because they’ll keep me on track so I won’t develop T2D. I mean, think about it, if you didn’t have to take insulin or watch your glucose levels, would you be disciplined enough to maintain a healthy lifestyle? Given the rising rate of T2D, even non-T1Ds are adopting these habits.

To learn about my personal five year plan, see my article, “Why I Haven’t Died Yet: My Fifty Years with Diabetes.”

I appreciate your concern about “double diabetes” in the conclusion. A lot of people look to medicine and scientific research for a replacement of doing the hard work to stay healthy, i.e. a health promoting diet, exercise, glucose control. While a cure for T1D would definitely remove a burden from nearly 10 million people globally, it does not even come close to the problem of T2D. Which do you think would be easier to cure? T1D or T2D?

Thank you for your clear and concise explanations.