Toni was completely deaf, but the most important thing I learned from her is knowing how to listen, and what to listen for.

We met at a hole-in-the-wall music club in the heart of Silicon Valley in 1985. She loved heavy metal/progressive rock because of its sophisticated drums and baselines, she said, because it was more visceral than the thumping of modern MTV pop music. She told me it’s hard for hearing people to understand.

“You hearing people listen for notes and lyrics that we deaf can’t hear. But we feel things that you don’t notice. Sound is made from vibrations, but not all vibrations make sound. You have to tune to a different frequency.”

I didn’t know it, but this was Toni’s philosophy of life. That night, we talked so much, it seemed to go on forever. Toni always signed when she talked—and she spoke well—but the signing was instinctual. She did it, even though she knew I couldn’t read it. That night, I learned how to sign some words and phrases, as well as the alphabet and numbers to a hundred, but it was just the beginning of a long learning curve.

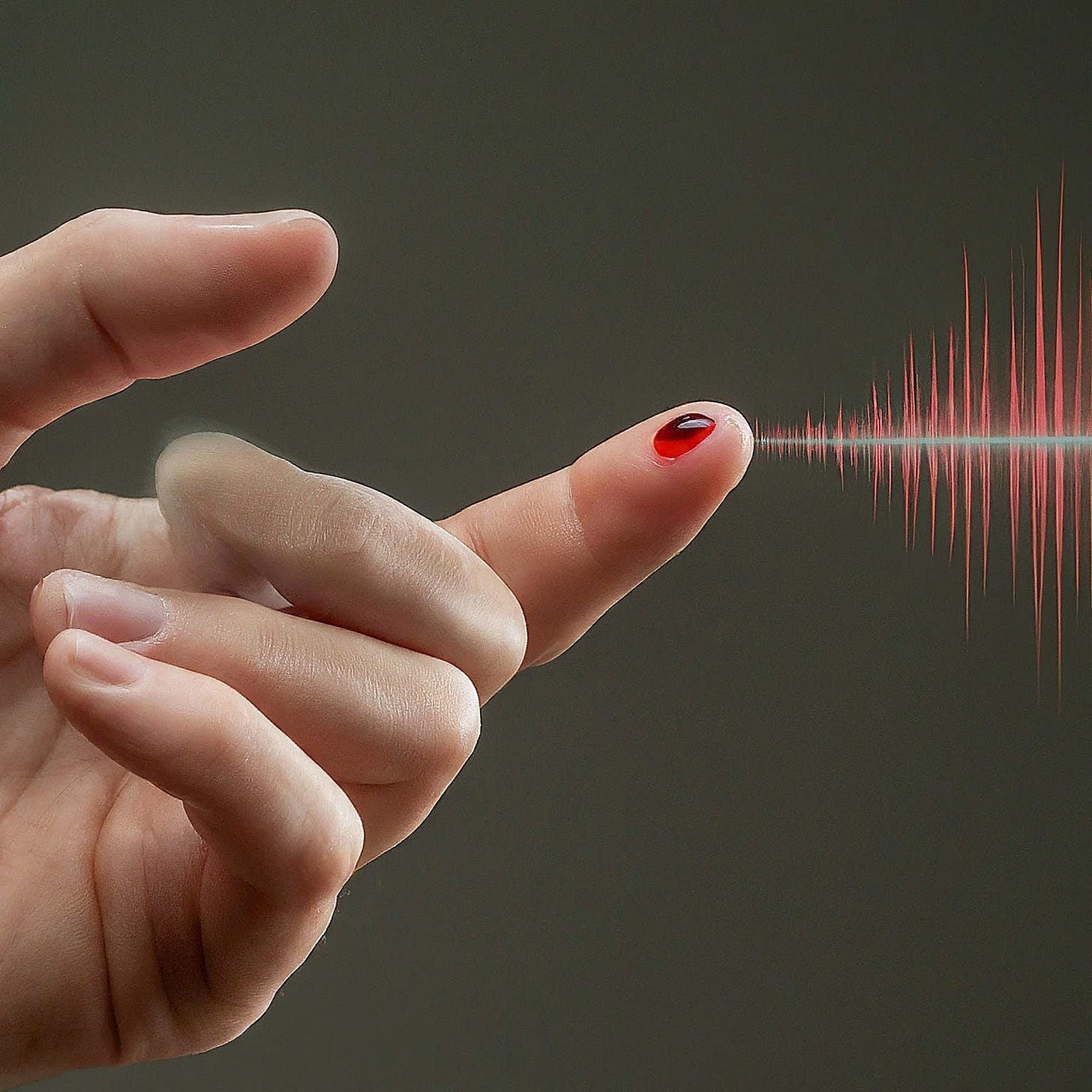

As for me, I shared that I was a type 1 diabetic—a T1D. I showed her how I took insulin and tested my blood sugar with a Dextrometer, one of the first glucometers available for home use. The devices weren’t entirely uncommon, most T1Ds probably had one, but I only used it occasionally. Unlike Toni’s signing, testing my blood sugar wasn’t instinctual. Heck, it wasn’t even a habit.

Soon enough, we got more intimate with how the other navigated the world. Toni had to deal with her deafness far more frequently and immediately than I did for my diabetes. I only had to take insulin a few times a day, but she was constantly dealing with things that required her attention 100% of the time.

People had to face her when they spoke so she could read their lips; she couldn’t make phone calls; driving required far more attention to what’s going on in traffic that we hearing people pick up on; she couldn’t listen to the radio or watch most television stations or movies, unless they had subtitles. In 1985, the web didn’t exist, so she couldn’t look things up, send email, text or communicate with anyone. She relied mostly on newspapers and magazines for information about the world.

Living as a deaf person required attention at every moment. It was her lifestyle. It was instinctual. And yet, to Toni, these were little things, minor inconveniences.

One night at dinner, I told her I was so impressed with how well she was able to live in a hearing world. “How hard it must be!”, I said with both support and sympathy.

Her response was quite unexpected—a combination of surprise and dismissiveness.

“Are you kidding,” she began, signing with her hands with greater enthusiasm than usual. “Being deaf is not that hard at all. Sure, you have to learn how to sign, read lips, and manage other things, but these are merely tasks, quickly learned. And yes, there are always people or situations that are frustrating, even maddening or insulting, but that’s life. I feel as normal as anyone else.”

She paused when she noticed I didn’t expect her to be so complacent. She reached out to take my hands in hers and rest them on the table between us. After a moment, she pulled them away to sign again.

“For the past three months, I’ve seen you suffer some hard situations with your diabetes,” she said in a more compassionate tone. “Waking up in a sweat at night is horrifying for me to watch, and that’s happened at other times as well. Dinner, on hikes, everywhere. Not all the time, but often enough. I can’t imagine what it’s like for you. In that way, I can understand how living with diabetes can be really hard. But managing diabetes? To me, it doesn't really look that hard to me at all.”

Wait. Come again?

She continued, “What really strikes me—the thing that I don’t think you appreciate—is that what makes managing diabetes hard is not the tasks themselves. It’s the fact that you don’t actually have to do those tasks. You can live, navigate the world, and do most anything without actually taking care of yourself. That’s what makes it hard.”

That caught me off guard. I was shocked.

She continued. “You don’t have to test your sugar. You don’t have to take insulin before a meal. You can eat anything you want. You can pretend to live as though you didn’t have diabetes, and you do it to feel ‘normal.’ But it’s only temporary. Bad things catch up to you, and when that happens, that’s when you bother to take action. When your sugar drops, that’s when you eat. When your sugar tops 300, that’s when you take insulin. You always seem to react with surprise and earnest frustration when things go wrong, and that’s when you take corrective action. I get it, but what I don’t get is why you never do the things you’re supposed to when you’re supposed to. Why don’t you take insulin before your sugars go out of whack? That’s a mystery to me, and to me, that should be easy.”

I had to sit with it for a moment. Toni chimed in again, but this time, she didn’t speak, she only signed. I couldn’t understand, so she signed again. Another pause, nope. Nothing. Then signed again. I looked at her with a “c’mon” stare as if to say, “Ok. What are you doing...”

This time, she spoke, but didn’t sign. “You don’t know what I said because you haven’t learned sign language. Why? Because you don’t have to. So long as I speak to you, we can communicate, therefore, you don’t learn it. I sign all the time, so you could learn it. It might take a while, and it might be frustrating, but over time, it becomes natural and you never think about it. But you don’t because you don’t have to. There’s no downside to not learning sign language… for you. I don’t have that luxury. What makes managing diabetes hard is that you give yourself permission to avoid it.”

She paused again. We watched each other closely. She then started to speak, but this time, carefully.

“Are you a diabetic, or a person with diabetes? Because to me, you act like the latter: Someone that doesn’t want to take care of themselves. There’s a big difference. I can’t avoid the things I do because I can’t hear. I’m deaf, and I don’t go around life pretending I’m not. If I was a normal person who was just hard of hearing, then I’d get into the same trouble you do. You treat yourself like the disease is not part of who you are. That’s what’s throwing you out of whack all the time.”

She was simplifying a point in order to drive it home, because we both knew that adapting to your condition, whether deafness or diabetes, requires stamina, acceptance and self-discipline, and not everyone is suited to that. I’d met a few people through her community who became deaf after they’d been hearing for many years, and yes, they have a harder time accepting it, and therefore, are resistant to doing the tasks. Similarly to those with T1D, especially when they get it as a teen or later. The day you’re diagnosed with T1D, “normal life” is whisked away from you, like a thief in the night, leaving many to feel angry and resentful. Sometimes, guilty and shameful.

I admit, I never had those issues. Many T1Ds suffer from mental health problems because building a new life of new routines requires self-discipline, and many can’t do that easily. But where the two groups diverge, it seemed to me, was how people are taught to think about their conditions in the first place.

T1Ds are taught that managing the disease is about abstinence—curbing one’s natural, normal desires. T1D is a negative thing, it’s a deficit, it’s a disease that you have to overcome. It’s a battle, and it’s hard. You have to be a warrior. To do things when you need to do them is a fight. That’s the message T1Ds hear all the time, so they are predisposed to believing it. It’s no wonder they say it to themselves.

But when it comes to acceptance and how people are taught to deal with their condition, deaf people aren’t exposed to this kind of apocalyptic rhetoric. It’s more frank and matter-of-fact, so, most get over the self-discipline struggle quickly, learn the tasks, and apply them in their daily lives. I’m hardly an expert on the dea community, but Toni tells me this just isn’t an issue within them.

We both sat with that for a minute, and then we both said at the same time, “At least we’re not blind!” We both laughed at that, but then I reminded her that T1D is a primary cause of blindness. The laughter stopped.

Still, something felt incomplete for me. “I think there’s another aspect to this that’s also worth noting,” I said. I paused for a moment to gather my thoughts.

“While T1Ds are fed these negative connotations, they’re also told that there’s hope right around the corner. There’s a cure, or a technology, or something else that will ease the burden, if not make it all go away. When I think about it, T1D has aspects that resemble a religious order that you didn’t want to join: The world is horrible and crumbling, so you must sacrifice and abstain, but it’ll all be over when the divine ‘cure’ comes to save us.”

I paused to reflect back to when I first learned I had T1D. “I was ten,” I told Toni. “And this is a story I don’t think I’ve thought about since then.”

“When I was diagnosed in 1973… yes, 12 years ago… They assured me a cure was only five to ten years away, and all I had to do was just stay alive. Take insulin, they said. Try to eat well, they said. They’re getting closer to a cure they said. They’ve succeeded with lab mice, they said. All I have to do is hang in there just a few more years! To me, diabetes was supposed to be a temporary thing. And everyone treated me with sympathy. ‘Aw! It must be so hard on you!’, people would say. You grow up thinking it’s hard because they tell you it’s hard. Ok, it’s hard, but then your parents yell at you because you’re not doing something they think you should be doing, making it all worse.”

I changed my tone to mimic the adoring and optimistic preacher at the altar. “But, then the doc says, don’t worry, a cure is coming, the suffering will be over, and you will be saved.”

I reverted back to my natural tone: “There are so many mixed messages. And yet, no one ever said what you’ve been saying, that managing the disease doesn’t have to be a negative thing, and that maybe it just requires paying closer attention more often. If that’s all it really is, it’s a secret that people don’t talk about.”

We sat quietly for a few minutes, Toni looking at me with compassion. This time, she spoke without signing. “You know, the deaf community is constantly learning how scientists are on the cusp of implants to cure hearing loss. But here’s where we probably part on this idea of a cure: I have no concept of sound at all. I don’t know that I want to be cured,” she said, emphasizing the word ‘cure’ as though it were an offensive slur as she squeezed my hand tightly.

“I can’t speak for others, but this is my life as I know it, and I love it. Now, I know that isn’t the same for you—diabetes is a true health problem, so you’d want to be cured. But deafness doesn’t have long-term consequences like that. In this way, we have a different sense of identity.”

Wow–I didn’t expect that word, identity. Never have I identified as a diabetic. Toni’s sense of identity was an unexpected proclamation of self. I wondered how I’d be different—or if I would manage my T1D differently—if I embraced it the way she embraced being deaf.

This whole conversation had me rethinking everything. In this new light, I considered treating T1D as if there won’t be a cure, nor is the world falling apart. I needed to unlearn these mantras and be more level-headed.

I said in a resigned voice, “I’ve heard there’s a new blood test called, ‘hemoglobin A1c’ and it’s supposed to tell how well your diabetes has been under control for the past few months. Apparently, you’re supposed to get it done twice a year. They don’t know what to make of the results yet, but my doc told me there’s a very large nationwide trial for diabetics to see what the health correlations are between A1c levels and long-term complications, like blindness, kidney disease and heart disease. It’ll take years before they see the results, but my doc thinks there’s a strong correlation to glucose levels and complications, so he wants me to test my blood sugar more often and dose insulin more tightly because he thinks that’ll reduce my risk. Your perspective here makes me think I should be more engaged with my tasks. And yeah, maybe it won’t be ‘hard’ to do them. I just need to choose to be that way.”

I had the doc order an A1c the next day, and the result came in: 8.5%. I had no idea what to make of that, but my doc was pretty clear: Keep glucose levels in range. The tighter the control, the better.

From that point forward, I did what Toni suggested: I tested before meals, I took insulin for what I was about to eat, and tested before bed. In each case, I would take appropriate measures in advance of what I anticipated doing next. And she was right–none of this was hard, or time-consuming. I wasn’t fighting. I wasn’t a warrior. I just had a routine.

True, it wasn’t easy to know how much to dose in any given situation, and I would still get those late-night hypo events, prompting me to say, “See? This is hard!” But Toni and I both knew what I meant: It’s hard to make a technical decision on dosing, and it’s harrowing to experience extremes. But, those experiences are different from the tasks. It’s not hard to commit to doing the tasks. Once you separate the two experiences, it’s easier to stick to the commitment.

Just as Toni said, the tasks became natural and second-nature, to the point where we actually had fun with them. One time at dinner, I tested my blood sugar twice in a row, which I’d never done before, especially because test strips in 1985 were $1.50 each! (That’s $4.35 in 2024 dollars.) Interestingly, both readings were pretty far apart from each other. Something like 220 and 180.

We looked at each other with curiosity. She said, “Test again!” So, I did, and it was 160. This really was curious. A few minutes later, I tested again. 140. And that’s when she asked, “How do you feel?”

I told her I felt fine–that I didn’t feel a thing.

“No,” she continued while signing, “Close your eyes, stop, and think of nothing. Tell me what you actually feel.”

I stopped and sat perfectly still. What did I feel? That was an exercise I never did before. “The restaurant is too noisy,” I said.

“Tune it out. It’s just a vibration. Tune to another vibration. Your diabetes. Tune yourself to that.”

In my mind I sensed glucose running through my veins, heading towards my muscles and tissues and my brain. I noticed my heart rate, my hands, my feet, the temperature in the room. After a few minutes, I felt a small hint of that sensation I’d get when my sugar was low. I opened my eyes and tested again. My sugar was 95.

“That’s amazing,” I said. “I could feel something at 95! I’ve never felt anything at 95.”

“So, what do you do? What does that mean?”, she asked.

“Well, I suppose my sugar must be dropping fast, so I better eat before I’m sweating all over the table. Again. And we have to tell the waiter to bring me a coke. Again.”

I started wolfing down the bread on the table. We looked at each other, waiting. About ten minutes later, my meter read 105. I said with amazement and relief: “I never would have known to do that if I didn’t run all those tests back-to-back.”

Diabetes has no sound, but it sure has a lot of vibrations if you know to tune into them.

Three months later, my A1c was 7.3%. The year after that, it was 6.5%.

As it happens with life, it brings surprises. I got a new job north of San Francisco, about an hour away. Toni and I got together now and then, but she also moved on, and we just faded. This is also when my professional life picked up. I wrote a couple of books on user interface design in the late 1980s, and ended up starting my own software company developing electronic mail in 1990. That whole experience led me smack dab in the middle of the internet startup craze of the 1990s. I wrote four more books on the economics of the photography industry, as well as columns in trade journals. In 2010, I founded the Center for Entrepreneurship at the University of California, Santa Cruz, with a focus on the life sciences. It was there that I started a medical diagnostics company, where I became fully immersed in the medical field, where I learned how to read and understand medical literature.

Ironically, I was so busy that I just paid less attention to my diabetes because, as Toni said, I didn’t have to. My A1c’s drifted upward, along with my age. By 2018, I was in my late 50s–and T1D had been taking its toll. As much as I’d come to learn about the medical and science side of diabetes, I was reminded that knowing about it is irrelevant if you don’t actually pay attention to it and treat your disease.

I decided to get a continuous glucose monitor (CGM), a device that sticks to your arm or abdomen that constantly reads glucose levels. Not only did I no longer need a finger-prick glucometer, but the device produced a continuous, real-time graph of my blood sugar levels. The data helped me see patterns that were previously unavailable, allowing me to further refine my glucose control: more insulin in the mornings, very little at night, and subtler nuances with exercise and certain foods. My A1c levels dropped from 7.4% to 6.5%, back where I was when I was with Toni.

Then in 2019, I happened to see the movie, “The Sound of Metal,” about a punk metal drummer who suddenly loses his hearing, and along with it, his sense of identity. There was that word again: identity. The film reacquainted me with the concept of what it means to stay engaged and present with my T1D, to accept it, and make it part of my sense of self. This was the reminder I needed to really get myself into gear.

While my A1c’s were good, I was still getting hypos at night, and the latest research made it very clear low glucose levels were as dangerous as persistently high levels. My previous method of guessing how much insulin to take turned into a more artful analysis of what my body was actually doing. With the help of my CGM, medical knowledge, and my empirical experiences over time, I fine-tuned my management techniques, and for lack of a better word, I call it intuition. I just know what to do better than I used to, but I could only do so if I remained engaged. Simply paying attention is the real key.

By 2021, my A1c dropped to 5.5%, with very little hypoglycemia at night, and even rarer glucose spikes above 200. Best of all I felt normal–this is my life, and I love it. It’s not work, nor is it hard. I wouldn’t even call it self-discipline anymore. It’s just what I do. I don’t worry or stress about T1D.

People sometimes ask whether I think there will be a “cure” for T1D, and I always reply, maybe not for people, but lab mice are going to be fine.

Yay, mice. Yawn.

Still, if there were a cure, I’d probably take it. But it does make me think about what Toni said about her never wanting to hear, even if they could cure it. In her case, being deaf is the only world she’s known. I have developed a good, healthy lifestyle that, ironically, I was probably only able to do because I have diabetes. It forced me to behave in ways that I might not bother to do if I had a working pancreas. Might it be that being a T1D actually made me healthier than I would otherwise be? I suspect I’ll never know.

I should point out that attaining this level of glycemic control is highly, highly unusual. There are those who earnestly pay just as detailed attention to their T1D and do not achieve results anywhere near what I have. It’s not for everyone, and I am cognizant of that. If you’re curious about my actual management protocol, you can read about in my article, “Why I Haven’t Died Yet: My Fifty Years with Diabetes.”

The point is that self-management really comes down to a frame of mind, a constellation of tools, most of which are largely tasks that you commit to. And when you do, they are habits—tasks that become so routine, you don’t even notice them. And none of that would be possible unless it was incorporated into my sense of identity. That’s the vibe that’s always there; you just have to learn to tune into that frequency.

Thank you for posting this really great article! I got type 1 diabetes in 1974, so I can really relate to your journey. We didn't even have meters back then. I thought your article's comparison of diabetes to being deaf was quite illustrative and helpful. I'm very grateful I'm approaching my 50th anniversary of taking insulin, and I'm grateful to still be alive and be enjoying being on this planet as it turns around everyday.

Scotty

Thank you, I enjoyed reading about diabetes from a deaf person's perspective.