Ideal Healthcare: Good, Fast, Cheap. Pick Two.

Explaining—and fixing—America’s healthcare crisis starts by understanding the “two-out-of-three problem.”

It feels like our healthcare system is terrible.

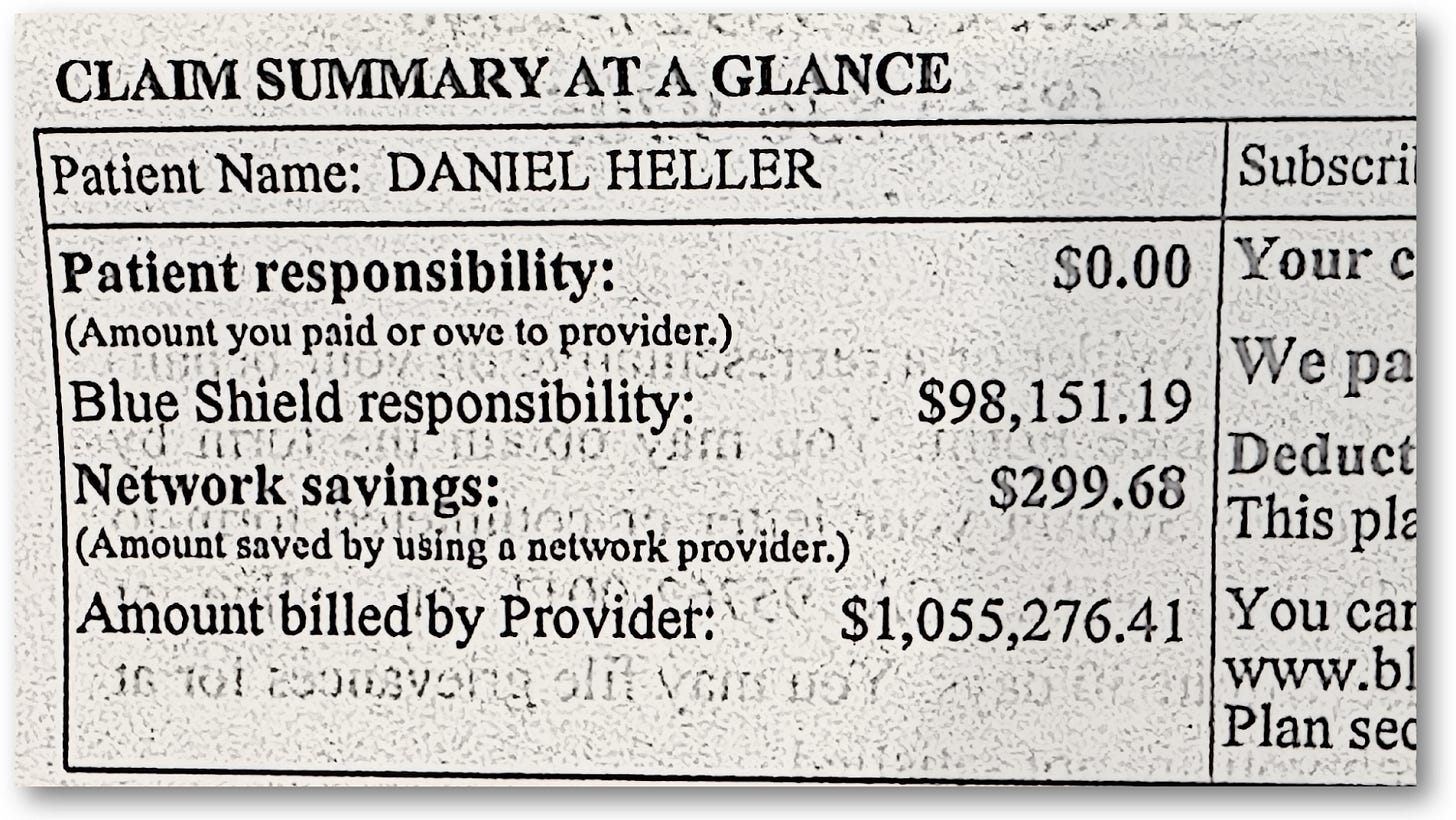

The “Explanation of Benefits” statement above is a good illustration of this, where Quest Diagnostics billed my insurance company $1,055,276,41 for a standard blood panel and lipid profile. What’s up with that? More on that later.

I’m sure you know exactly what the problems are within the healthcare system, and you’re absolutely sure who’s to blame, and how to fix it. Of course you do—everyone does.

One idea comes from the local mayor of the Italian village of Belcastro, who came up with a novel approach to mitigating healthcare costs by mandating that people “avoid contracting any illness that may require medical assistance.”

According to BBC News, the mayoral decree mandated that people stay home and do nothing because—get this—the roads were almost “more of a risk than any illness.”

His mandate was intended to be humorous to call attention to the problem with healthcare in his province of Italy. And yet, Americans love the idea of adopting a nationalized healthcare system, such as those implemented in, you guessed it, Italy. But also Canada, Europe, and virtually everywhere else. All the while, those countries look to America’s healthcare system as a model they wish to adopt—or, at least, portions of it—so they can leave home again.

Everyone’s healthcare system is clearly in need of, well, care. No element within any system is all that healthy: insurance, drug companies, government regulations and funding. It’s a complex problem.

This article doesn’t aim to solve any of these, blame anyone, excuse anyone, or even propose ideas. Rather, it is to provide a better framework for how to think about our healthcare system in ways that can help evaluate proposed solutions, including those silly-but-sometimes serious proposals, like outlawing getting sick in the first place.

That framework that I’m referring to is an age-old principle of economics: The Two-out-of-Three Problem.

The Two-out-of-three Problem

The Two-out-of-Three Theory involves three principle factors involved in any relationship where a good or service is provided: Quality, Cost and Speed. Whether it’s construction, food services, an auto repair shop, or running a healthcare system, the two-out-of-three problem affects everyone engaged on both sides of a business relationship.

An early example of when this phrase was used in modern commerce is from the 1921 book, “Concrete: Its Manufacture and Use,” which contained the following passage:

“The owner for whom the work is being done, be he an individual, a corporation, or a government agency, is interested in quality, speed and cost. The contractor and the construction superintendent are interested in cost, speed and quality. The sequence of these items is in accordance with their relative importance to the two parties to the contract.”

This last line is the most essential: The sequence of these items has varying importance, relative to who’s providing or receiving the service. Keep this framework in mind throughout the rest of this article, and while you do that, think about which should take priority over the other two.

Summarizing our current healthcare system’s dysfunction

I’ll be as brief as I can.

First, the Earth cooled. Then the dinosaurs came. Then came World War II. Then came a huge expansion of American economic and technical innovation during the 1950s and 1960s. That’s when America shifted away from government-funded care (because we didn’t want to mimic communism and socialism) and towards employer-sponsored insurance.

Because the cost for insurance was paid for by employers, everyday Americans rarely saw or felt the true cost of healthcare, so America’s cultural norms shifted away from costs, and towards quality and speed of healthcare.

If we break a leg or need a heart transplant, we want it taken care of now and by the best doctors. We also love choice—we want to choose from a very large menu of options, whether it’s doctors, drugs, vaccines, or even unregulated over-the-counter placebos that non-expert influencers sell through social media.

This worked for a few decades, but the number of Americans without access to health insurance continued to rise, which led to the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare). Interestingly, the ACA was modeled on a Republican model called Romneycare, officially known as the Massachusetts Health Care Reform Act of 2006, devised by Mitt Romney, the Republican governor of the state. Key provisions of Remoney care—which was copied directly into Obamacare—were:

Individual Mandate: This was a central component, requiring most adult Massachusetts residents to obtain health insurance. Those who could afford it but chose not to face a tax penalty.

State-Run Health Insurance Exchange: The law created a marketplace called the "Health Connector" where individuals and small businesses could purchase subsidized health insurance plans.

Employer Responsibilities: Employers with more than a certain number of employees were required to offer health insurance or contribute to a state fund.

Expansion of Medicaid: The law expanded Medicaid eligibility to cover more low-income residents.

The ACA actually went further in many ways, but a key factor was to force insurance companies to spend a certain percentage of collected premiums—80 or 85% depending on the type of insurer—on healthcare, leaving the rest to overhead and profit. This significantly capped insurers’ profit margins with the intention that the cost of medical care would be optimized, thereby creating more efficiency.

The good news was that the ACA successfully reduced the number of uninsured Americans from 45.2 million people (14.8% of the population), to 26.4 million (8.0%) by 2022.

The bad news is that the ACA became a victim of its own success: Because the number of insured Americans grew by over 18 million people, the supply of doctors, services, infrastructure and other aspects to healthcare didn’t meet the demand, so as all Econ 101 students learn, when demand outpaces supply, costs grow. In this case, the per-person cost for healthcare grew from $8,400 to $13,493 today.

The imbalance of supply and demand in healthcare doesn’t just affect basic costs, it changed the financial incentive structure away from preventative services, and towards procedures, the kind that treat problems. In other words, doctors make more money by actually performing procedures on you, rather than the services that kept you healthier in the first place—you know, like learning how to eat properly and exercise.

So long as you don’t get sick, the system works perfectly!

But, unlike the village in Italy, the ACA didn’t outlaw getting sick. As this incentive structure shifted, so did the medical professions that newly minted doctors entered. The following chart from the Medscape Physician Compensation Report for 2024 shows the average annual compensation by medical speciality.

Notice that the top-paid specialties are those that perform the most expensive procedures, with over a two-fold higher income than those at the bottom of the list, who don’t perform any procedures, but generally keep people healthy, such as primary care, family medicine, mental health, and so on. In fact, there are major shortages in all these lower-income medical specialties (according to the AMA).

So, people just keep getting sicker.

Consider endocrinologists, people who specialize in diabetes and other metabolic disorders. The rise of type 2 diabetes in the US is skyrocketing, with an estimated ¾ of Americans—over 200 million—either having T2D, or are “pre-diabetic,” or suffer some other metabolic disorder that requires the expertise of an endocrinologist.

But the number of endocrinologists is at an all-time low and dropping fast, as medical students are not going into this field. It’s not like they’re seeking to get rich; these students have to pay for medical school, where the cost has risen significantly over the past ten years. In the article, Average Medical School Debt, “the average medical school debt is $234,597, excluding premedical undergraduate and other educational debt.” Accordingly, students are pursuing higher-paying specialties to repay their loans, according to an NIH analysis, “Medical students in distress: a mixed methods approach to understanding the impact of debt on well-being.”

With the rapid increase in the rate of T2D—especially in rural areas of the US—the desert of endocrinologists can have a huge impact, not just on the cost of treatment, but in the lack of doctors that can treat and help prevent the disease.

The map below shows that over two-thirds of U.S. counties lack endocrinologists, according to aggregated data from GoodRx’s article titled, “Endocrinologist Deserts: A Critical Healthcare Gap for Millions in the U.S..”

When diabetes is not treated, or not treated properly, it leads to amputations, kidney failure, heart attacks, and a constellation of other problems, all of which, you guessed it, require procedures, costing the healthcare system even more money.

As Senator Everett Dirksen, Republican senator from Illinois in the 1930s once said, “A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon, you’re talking about real money.”

Trying to figure out how to fix this system is complex, because many entities in the healthcare ecosystem have a stake in it. Let’s start with the one you’re thinking about now.

Insurance Companies

Remember, before the ACA, the number of Americans without access to insurance at all was rising fast, as was the price of healthcare, so the goal of the “Affordable Care Act” was intended to make healthcare, you know, affordable.

To do so, insurance companies offered lower-tiered plans that met the minimum level of required care mandated by the ACA. “Minimum care” was intended mostly for those who are young and healthy, who didn’t need the kind of premium plans that normally come with employer-based insurance. The problem is, most people signed up for it, and unintentionally shifted their priority from quality to cost. And that lower cost came, well, at a cost.

And that was fine, so long as you don’t get sick. But that didn’t quite work out so well.

The rise of preauthorization requests and claim denials

As people tried to utilize these new plans the way they were accustomed to with the old ones, it led to a rapid rise in out-of-pocket expenses, pre-authorization requirements, and claim denials.

And complain, people did.

According to the report, Claims Denials and Appeals in ACA Marketplace Plans in 2021, denial rates for in-network claims increased progressively since the ACA, where it now goes up to nearly 50% among different insurers. Initially, this rise of claim denials was due to a mismatch between one’s choice of plan coverage and their actual health needs (people didn’t think they’d need the higher-tiered plans), but it progressed due to other confounding factors.

As the incentive structure for medical care shifted towards procedures, the claims that patients were submitting to insurance companies were also becoming more expensive and, in many cases, questionable.

And where money flows, bad actors follow: a growing prevalence of medical groups owned by private equity (PE) firms. These investment groups have hoovered up large numbers of small medical practices of individual doctors that typically specialize in various fields of medicine (including veterinarians), and once they have a near monopoly within a community, they raise prices—a lot.

According to the report, Private Equity’s Role in Health Care, PE-owned medical practices are encouraged to increase utilization of more frequent or more intensive procedures, to generate more revenue.

The “questionable procedures” problem, which was already expensive, multiplied rapidly, leading to an even larger increase in claim denials and preauthorization requests.

And the problem is projected to get even worse: Remember those medical school students looking to pay their student debt? They’re just adding more people to the most expensive part of the healthcare system because, well, that’s where the money is.

Oh, we’re not done yet.

And this problem is an edge case of a more rampant problem: medical insurance fraud.

When such practices of overbilling or unnecessary procedures are high enough, it can be deemed as a form of health insurance fraud, a phenomenon that costs the U.S. healthcare system tens of billions of dollars annually. According to a report titled, “The Challenge of Health Care Fraud,” published by the National Healthcare Anti-fraud Association, government and law enforcement agencies place the loss as high as 10% of our annual health outlay, which could mean more than $300 billion (as of 2018 when the report was published).

In a 2024 Dept. of Justice report, such fraud can include both provider- and patient-initiated schemes. Providers often bill for services not rendered, upcoding (billing for more expensive services than provided), billing for medically unnecessary services, and submitting false claims. Patients commit fraud by providing false information to obtain coverage, using someone else's insurance card, and forging prescriptions. Then there’s Organized Criminal Groups who engage in large-scale fraud schemes, such as identity theft, durable medical equipment fraud, and prescription drug fraud.

All this complexity also leads to more mistakes, including innocent coding errors, where honest providers and patients are wrapped up in red tape. The graphic I showed at the top of this article showing over $1M for lab work was exactly that: a coding error. Even though I wasn’t on the hook for it, when I called my insurance company to enquire about it, they told me that someone in the administrative chain accidentally entered an incorrect billing code that happened to be really expensive. (I wondered whether anything would have been done about it had I not caught it and called it in.)

Not all outrageous costs are innocent, of course, but sometimes the line is blurry. Is a given procedure truly necessary? Is the cost appropriate? When consumers are denied claims or have preauthorization requirements, they have no idea whether these are legitimate. Social media explodes these into the stories we see and hear, especially the very sad, true, and most sensationalized stories. People think this is now the norm.

Applying these estimates to total U.S. healthcare spending (which was around $4.5 trillion in 2022), healthcare fraud and other mismanagement accounts for losses up to $450 billion annually.

In order to keep up with it, insurance companies have since increased premiums and denial rates across all their plans, not just the low-tiered ones.

Feeling overwhelmed? Try working for an insurance company, or frankly, any of the companies involved in the healthcare system. No matter who you are—a doctor, nurse, administrator, or virtually anyone—part of your job will entail activities that account for nearly ⅓ of the cost of healthcare: paperwork.

Administrative overhead

One of the largest costs of healthcare is administrative overhead. All these entities have to talk to each other, and that conversation is time-consuming, expensive, and stress-inducing. A US Senate report in 2018 estimates that administrative costs account for 15-30% of total healthcare spending, accounting for over $1 trillion dollars per year (confirmed in a related report).

Worse, administration actually interferes with actual care. In the paper, “Time and the Patient–Physician Relationship,” multiple studies show that doctors spend on average about two hours in “administrative tasks” for every one hour of actual care. (And yes, this includes dealing with pre-authorization requests and claim denials, which is taking progressively more time.)

Interestingly, studies show there’s a correlation showing that doctors prescribe more drugs when they don’t have sufficient time to properly dedicate to patients. That’s not “fraud,” per se, but it gets close to malpractice, which leads to yet another factor contributing to the cost of healthcare.

The increasing stress on the medical system, with fewer doctors, especially across specialties, leads to reduced quality of care, which not only reduces health outcomes, but also increases the number of mistakes. And when mistakes happen, Americans call lawyers.

As the number of malpractice claims has risen, so have doctors’ premiums on their medical malpractice insurance premiums. According to an analysis by medpli.com, the year-to-year premium increase nearly doubled from 13.7% in 2018 to 26.5% in 2019.

I’m sure you have tons of ideas that you’re absolutely sure will fix the system. Let’s review those.

Proposed Fixes

It’s at this point that people often point to countries with nationalized healthcare, such as Canada, Europe, and virtually everywhere else. The U.S. has the highest healthcare spending per capita among developed nations, yet it has worse health outcomes than many other countries, according to a detailed report by the Commonwealth Fund.

But again, it’s not that simple.

True, countries with nationalized healthcare have lower costs, but in exchange for that, care is rationed. In other words, speed. People often have to wait months for just about everything from surgeries to psychotherapy. American-style private insurance is also available in these countries to get faster access, but it’s costly—just as it is in America. But it gets you quality and speed. This is largely why other countries love our system as a model.

Then there are countries throughout Africa, where healthcare is very fast and free, but the quality is not nearly at the level of larger economies (again, except for those who can afford private insurance).

But it’s also not necessarily true that countries with nationalized healthcare are healthier when you consider factors such as diets, rates of obesity, rates of gun violence, handling of the opioid epidemic and Covid-19, that in the aggregate, have cost millions of American lives and reduced lifespan. But it has not been uniform across all fifty states. The following chart on life expectancy among states comes from the CDC.

Hawaii has the highest life expectancy at 80.9 years, while Mississippi has the lowest at 71.9 years.

In a comprehensive meta-analysis, “The Effects of Earlier Medicaid Expansions: A Literature Review,” the states that have accepted Medicaid expansion available under the ACA had significant positive effects on life expectancy, access to healthcare, mitigation of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other metabolic disorders.

And yet, there are other reasons for America’s healthcare crisis, so let’s review those.

Profit Motives

Most people think healthcare and insurance companies are hugely profitable, and their desire to pump up those profits for shareholders is the source of the problem.

There are definitely issues with how these companies contain costs, but as for profitability, that’s a tougher argument to make. For context, the 500 companies in the S&P stock index have an average profit margin around 15%, but the top healthcare companies’ profit margins are a fraction of that.

UnitedHealth Group is considered the largest healthcare company by revenue, yet their net profit margin is typically in the range of 5-7%.

CVS Health includes pharmacies, Aetna insurance, and a pharmacy benefits manager (PBM). CVS’s net profit margin tends to be between 1-3%.

McKesson Corporation is a major distributor of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, and their net profit margin is usually around 1-2%.

Cardinal Health is another major distributor of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, and their net profit margin is typically around 1% or less.

Tenet Healthcare’s net profit margin for 2023 was 2.49%.

As for insurance companies, they are also considered villains in this ecosystem, but their profit margins are also limited, primarily due to the Affordable Care Act, as mentioned above. The profit margins of the largest insurers (with others being equal or less than these figures) are similarly slim:

UnitedHealth Group (UNH): Once again, 5-7%.

Elevance Health (ELV) (formerly Anthem): 3-5%.

Cigna (CI): 4-6%.

Humana (HUM): (Medicare Advantage plans) 2-4%

CVS Health (CVS): 1-3%.

In other words, “profit motive” is the least likely of reasons for pre-auths or claim denials.

But this is hard to swallow for many people who feel that their insurance isn’t covering what they believe are necessary items. Remember when I mentioned that some claims are “blurry?” A good example is when type 1 diabetics (T1D) want to use automated insulin delivery (AID) systems, or even just non-automated insulin pumps. Many of them are denied these claims with the explanation that “their A1c levels are already in good control.” That is, they’re not sick enough to warrant the use (and expense) of insulin pumps.

This angers many diabetics, claiming that insurance companies are just looking to save money at patients’ expense. But it’s not that simple.

In my article, “Benefits and Risks of Insulin Pumps and Closed-Loop Delivery Systems”, multiple studies find that fully automated closed-loop systems absolutely help reduce A1c levels from >9% down to 7.5%, which is a huge benefit, saving lives and money, especially for children, teens, and those who are either unable or unwilling to self-manage their disease. Insurance companies reimburse for pumps when the patient’s A1c levels are above a certain threshold (usually around 7.3%) for these reasons.

But research shows that such systems can never achieve better A1c levels than around 7% unless the user is proactive in how they self-manage their diabetes. And if they are, it often doesn’t matter whether they use pumps or insulin pens.

So, if it doesn’t matter which they use, why do insurance companies deny the claims for pumps? Two reasons: cost and health outcomes.

The DIAMOND Randomized Trial found that pump users’ lifetime costs are $112,045 greater than those who use insulin pens, and did not yield healthier outcomes or improved lifestyles. In fact, users whose A1c levels were initially lower than 7% found their A1c levels rose when using pumps because of the moral hazard of such systems: Users tend to rely on automation and pay less attention to their disease—that is, they are no longer proactive in self management—so they end up doing worse than they were. This then leads to metabolic disorders associated with type 2 diabetes, a phenomenon called “double diabetes.”

According to the Lancet article, “Obesity in people living with type 1 diabetes,” only 3.4% of T1Ds were obese in 1986, compared to 37% in 2023, largely attributable to the complacency of using either automated systems, or following guidelines that promote the over-use of insulin to keep glucose levels under control. (Too much insulin leads to weight gain.)

Insulin pumps and insurance coverage is a prime example where patients blame the insurance industry for not giving them what they believe they need, even though that very denial can sometimes be in their own best interests.

The same cannot necessarily be said of pharmaceutical companies. Here, their profit margins are on par with the largest tech companies:

Johnson & Johnson: pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and consumer health products; 25-30%.

Pfizer: vaccines and pharmaceuticals; 20-30%.

Roche: pharmaceuticals and diagnostics; 20-25%.

Novartis: medicines; 15-20%.

Merck & Co.: medicines, vaccines, and animal health products; 20-25%.

Capping profit margins on pharma companies is on everyone’s minds, but arbitrarily imposing profit restraints could affect more than just the pharma companies, but the entire ecosystem under them, disrupting the entire economy, which collectively accounts for roughly 1.5-2% of U.S. GDP, with broader economic impacts potentially reaching 3-4% or more.

The problem isn’t so much that pharma companies are “profitable,” but that the market economy for their products is not entirely “fair.” That is, in a normal economy, buyers put pressure on producers by negotiating prices. Cars, homes, phones, agriculture, you name it. Companies compete with one another, but it’s the consumer that “negotiates” prices, either directly or indirectly, keeping prices (somewhat) in check.

But that’s not the case with drugs: Neither insurers nor healthcare providers have incentive to negotiate better prices because those companies don’t typically incur drug COSTS the way we’re used to thinking of it—they just pass them onto others (government, businesses, individuals).

Well, there is ONE buyer that can negotiate prices, but doesn’t: The government.

Government involvement

Many believe that the government should engage in direct negotiation for drugs to lower prices, but to do that, one has to use the Medicare model, which has been a political third rail among members of congress.

Medicare is, by definition, “socialized healthcare,” because everyone in the system bears a part of the cost. The problem with the word, “socialized,” is that it reminds people of the word, “socialism,” which has been demonized for so long, no one wants to touch it.

And yet, Medicare is hugely popular.

A less toxic-sounding way to characterize the role Medicare plays is a single-payer system, which is designed to reduce administrative costs, and provide stronger negotiation with drug companies. But that single payer is, well, us. Yes, we are the payer, and we pay those bills in the form of taxes (in one form or another).

While many Americans loathe the idea of higher taxes on themselves, they’re more than happy for someone else to pay higher taxes, but that problem is tough to solve in our current political environment, where “special interests” have a thumb on the scale. But it’s also not that simple. Remember, “special interests” are merely people who represent large constituencies of other people. Some special interest groups are working for you, while others are working for the other guy. What you really want are the special interest groups who represent you to convince lawmakers to make the other guy pay for healthcare.

Round and round it goes.

While you’re pondering whether you support the idea of a single-payer system—also called, Medicare for All—there are other ways to improve the healthcare system. That leads us to …

Efficiency

Two ideas that go in and out over time are “value-based care” (VBC), and “bundled care.”

In bundled care, services are coordinated among different specialists within the system, which also allows for economies of scale in transactions. For example, an “episode” might be a joint replacement procedure. Rather than paying separately for each aspect of the service that may be provided by different individuals, the entire package would be done—and charged—as a single event. A bundle. The hospital, the anesthesiologist, the doctors, the nurses, the drugs, the band aids and the two tablets of Tylenol you’re given would all be included in a single price, which would eliminate the huge overhead (paperwork) of billing all these separately. That’s right, in the current system, each of these are sent to insurance companies, who may limit payment, or restrict which of these bills are paid, and if so, how much to pay. That’s a huge amount of paperwork. (And you end up paying $8 for that Tylenol. Per pill!)

So, bundled care seems good right? But implementation is really hard. This brings us to the “value-based care” model, or VBC, which implements bundled care. This idea is currently implemented as an HMO (health management organization) like Kaiser Permanente (and many others). In order for these organizations to get all the service providers to work together—to agree on prices and processes that streamline services and procedures—the HMO has to virtually own each of these services, or have them under such restrictive contracts that it amounts to the same thing.

A VBC model achieves the primary goal of reducing costs, but the consequence is that patients can’t go outside of the HMO network, so the limitation of services and choices of doctors often constrains patients to too few options, not to mention a pretty rigid set of administrative judgements as to what kind of care people should get. And those options are limited because doctors and other specialists aren’t paid as well as non-HMO doctors.

Here, HMOs illustrate a classic case of the two-out-of-three problem, where care costs less, but at the expense of quality.

Priorities: Quality, Speed or Cost?

It’s one thing to debate the trade-offs between quality, speed and cost. But it’s another thing to consider what our priorities are as a society. Historically, we always valued quality and speed over cost, but this was largely because we could afford it. America’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is $27.36 trillion, as of 2023, so surely, one could imagine that healthcare should be somewhere near the top of our priorities list, where “cost,” while important, is not nearly the problem that other first-world countries have, such as England, France, Germany and Canada, whose GDPs are between $2-4 trillion.

Employer-sponsored insurance was fine, but it left out too many people who were ineligible for government-sponsored programs (Medicare and Medicaid). The ACA was intended to fill that gap, which it did, but the byproduct was a system that wasn’t able to grow to provide those additional services, which had the effect of skewing the incentive structure away from preventative services—which require a lot more people—to procedures. It was a way of saying, “as long as you don’t get sick, your healthcare costs are really low!” (The Italian mayor was onto something.)

There are those who argue that America’s huge GDP could easily handle a larger chunk of the cost of healthcare to bring quality back, but here’s a counterintuitive question: Does more access to healthcare actually achieve healthier outcomes?

In a paper titled, “Effects of Patient-Initiated Visits on Patient Satisfaction and Clinical Outcomes in a Type 1 Diabetes Outpatient Clinic: A 2-Year Randomized Controlled Study,” the authors enrolled 357 T1Ds in a two-year randomized trial conducted in Denmark, where the intervention group consisted of 178 T1Ds with unlimited access to outpatient visits, including the ability to call anyone on the healthcare team, get blood tests, or other services. The control group had 179 people, who were given access the usual way, through regular prescheduled visit similar to what traditional care entails.

After two years, those who had unlimited access had significantly higher satisfaction scores with their care! No surprise there. And yet, they achieved no improvement in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), LDL, blood pressure, and complication status. (See Table 3 for details.)

There’s no upper limit on how much you can spend on healthcare, but there seems to be an upper limit on how effective such care can possibly be.

At some point, people may need to consider the unthinkable: taking care of themselves by, you know, eating well and exercising. That’s right, just a simple walk can improve your lifespan by several years (not to mention quality of life), according to decades of studies, according to the paper, “Walking for Exercise,” from Harvard’s School for Public Health.

Or, we can just outlaw getting sick.

Ciao! Ciao!

I agree this is a complicated issue in the USA, and that no healthcare system is perfect. I'm an American living abroad, and my personal experience with T1D in 3 countries is contrary to the theory that we are limited to just two of the three: good, fast or cheap. I've lived in Uruguay, Argentina, and Spain, using the public healthcare system in all three countries. I also subsidize with private insurance in Spain (a holdover since before I was eligible for public healthcare). Each country's public healthcare system has been incredibly efficient with appointments and procedures, scheduled in days or weeks rather than months, with little to no copays. Facilities are modern, and doctors are compassionate and interested, often taking 30 minutes per patient, and never a worry about claim denials. All the same medications and equipment have been available to me for low/ no cost. Even for private health insurance in Spain, we're paying ~€400/mo for a family of 4, which includes a supplementary cost for T1D, with no additional copays/bills. I would take any of my international medical experiences over the exorbitantly expensive, complicated, and inefficient system in the USA.

Thank you for this ambitious essay on healthcare costs in the U.S.A., with accompanying remarks comparing to other nations' healthcare costs. Your photocopy of a large charge submitted to you in error is hilarious in a very dark way.

You did not even mention the IRMAAs which are one of the most socialized aspects of Obamacare. And yet, for many of us who are more or less "middle-class prosperous", NOT wealthy by American standards, these are a punitive aspect of Obamacare. They have nothing to do with inspiring, or directing resources to, better wellness outcomes.

The popularity of Obamacare rests on the fears of those who suspect that any change will leave them worse off.

That said, I should close by saying that in general throughout my life, I have encountered skilled and caring people in medicine, and I owe their contributions to helping me stay well to their personal commitments, not to any government program.

Thanks to them, and again to you, Mr. Heller.