A Hybrid Approach to Curing T1D: New, Novel and Not Yet

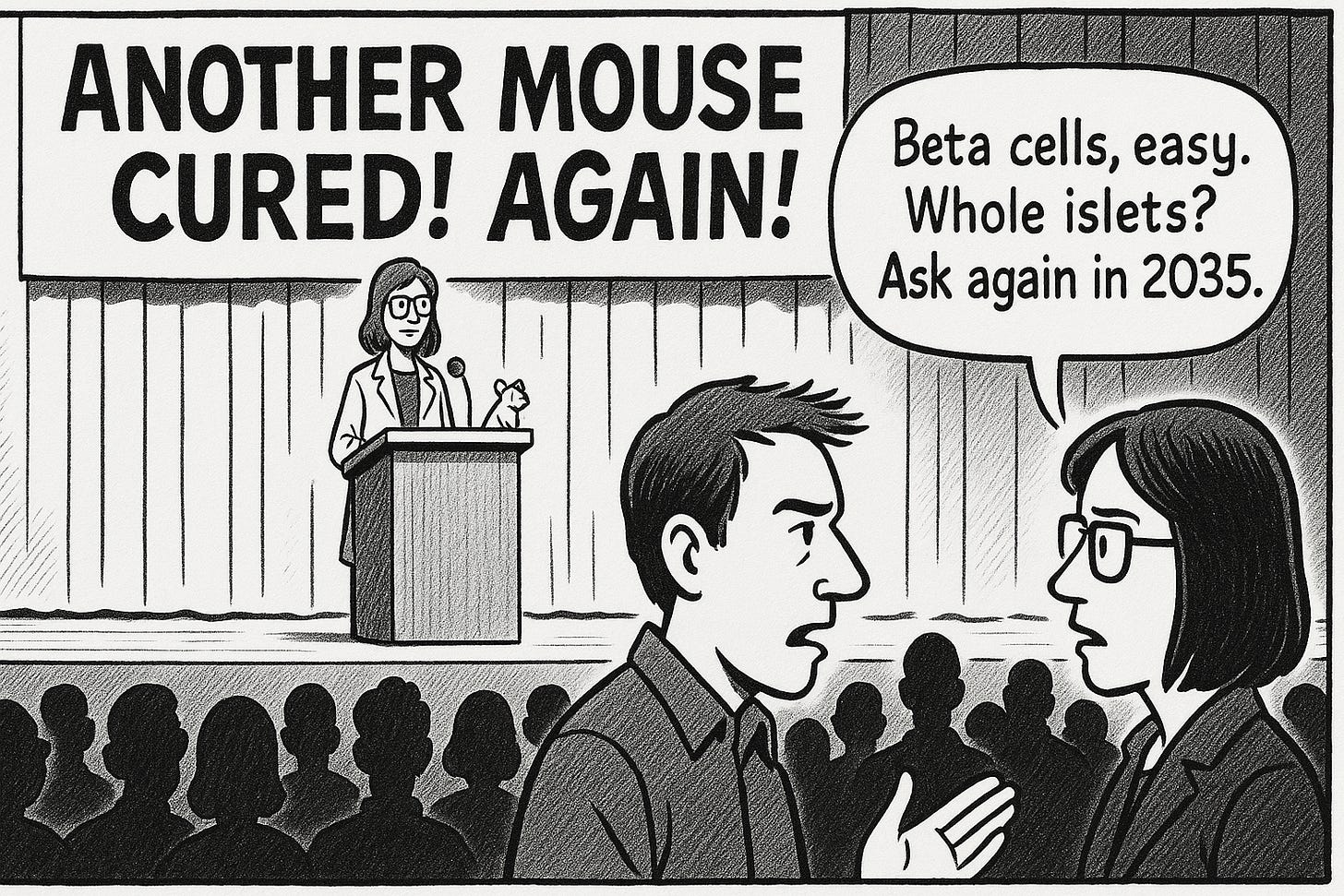

Spot the sleight of hand: Beta cell replacement is not enough. You need the whole islet!

A study published on November 18, 2025 in the Journal of Clinical Investigation from Stanford Medicine, Prevention and reversal of autoimmune diabetes by mixed chimerism and islet transplantation, is already making waves in the T1D community.

The results were striking: 19 out of 19 mice were prevented from developing T1D, and 9 out of 9 mice with established diabetes were cured. No immunosuppressive drugs required afterward. No graft-versus-host disease.

Pop the champagne bottles!

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple.

PRO TIP: The “sleight of hand” in these and other T1D-related trials is the subtlety that most people overlook: Beta cells versus whole islets. This is a big deal. You can’t just replace beta cells in T1Ds. They aren’t enough to maintain glucose levels. They are part of the whole islet that contains alpha, delta, gamma, and sigma cells—all of which are critical to glycemic regulation.

Yes, the immune system is a challenge, but that’s only HALF the battle.And this paper—and its results—never had any intention to approaching a cure to T1D. It was to demonstrate a way to deal with other autoimmune diseases.

The Immune System Challenge

The research in this study is important insofar as immunotherapies are concerned because it adds a new “fifth approach” to curing all sorts of autoimmune diseases. In my earlier article, What a ‘Cure’ for Diabetes Might Look Like, I surveyed the landscape of research aimed at freeing T1Ds from insulin dependence. A primary (but not sole) challenge with all autoimmune diseases is the immune system: it produces antibodies that attack beta cells, and any path to a cure must deal with this somehow. I used a police force analogy to frame the four main approaches researchers have pursued. We’ll continue with that analogy to help put this new paper into context.

Think of antibodies as cops whose job is taking out bad guys (viruses). the problem is that some of the cops mistakenly target the good guys—the beta cells that make insulin. You can suspend the police force (immunosuppressants, which leave you vulnerable to infections), wall off the good guys (encapsulation, which faces fibrosis and oxygen-supply problems), send in a negotiator (monoclonal antibodies like Teplizumab, which delay but don’t prevent T1D), or replace the police force entirely (CAR-T therapy, which is promising but costs $500,000 per patient and requires chemotherapy).

Each approach has shown success—mice get cured constantly—but each runs into the same fundamental obstacles: the immune system adapts, donor cells are scarce, and what works in mice rarely translates cleanly to humans.

My article basically says that a cure won’t arrive as a single dramatic breakthrough but as a gradual accumulation of iterative advances, each with trade-offs, until some combination eventually crosses a threshold.

This is another way of saying, “think about it more, tinker with it longer, turn it upside down, and then finally pass it onto a postdoc to try out on more mice with another $150K NIH grant.”

That’s not to say this new research isn’t a huge advancement in science and research into the immune system. It is, so let’s examine that more closely.

The Hybrid Police Force

The Stanford team created a hybrid police force: a stable coexistence of donor and recipient immune cells, technically called “mixed chimerism.”

Here’s how it works: Researchers gave mice a “gentle” pre-conditioning regimen—immune-targeting antibodies, low-dose radiation, and a drug used for autoimmune diseases—just enough to create space in the bone marrow.

Then they transplanted blood stem cells and pancreatic islets from the same donor. (See the slight of hand there?)

The result was an immune system containing cells from both donor and recipient, which accomplished two things simultaneously: it accepted the foreign islets as “self,” and it stopped the autoimmune attack on beta cells generally.

All the mice were cured!

The approach builds on work by the late Samuel Strober at Stanford, who showed that hybrid immune systems could enable kidney transplants to last decades without rejection drugs. The key innovation here is making the pre-conditioning safe enough for people whose condition isn’t immediately life-threatening—exactly the barrier that’s kept stem cell transplants confined to cancer treatment.

As study co-author Judith Shizuru put it, the challenge has been “diminishing risk to the point that patients suffering from an autoimmune deficiency that may not be immediately life-threatening would feel comfortable undergoing the treatment.”

Why This Doesn’t Affect T1Ds AT ALL

While reprogramming the immune system in this way was novel, the reason it doesn’t affect T1Ds is the same reason why the Edmonton Protocol didn’t work back in 2000: The donor problem.

The protocol requires blood stem cells and islets (yes, ISLETS) from the same deceased donor.

A viable cure for T1D cannot rely on donor islets from cadavers: It’s not scalable, among other problems. Any approach that uses donor cells is no longer considered a viable candidate for a “cure”. Instead, such experiments establish a proof-of-concept. And we’ve known this since the Edmonton protocol in 2000.

The researchers acknowledge this, but then gesture towards solving that problem by generating large numbers of islet cells from pluripotent stem cells as a solution.

Wait. What? Did you miss that? Perhaps, so let’s zero in on that statement: “Generate large numbers of islet cells from pluripotent stem cells.”

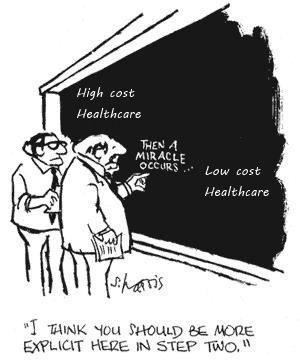

It reminds me of this cartoon where two scientists are working out a problem on a blackboard, and part of the “equation” has the text that reads, “Then a miracle occurs.”

Whether stem cell research can eventually produce functional complete islets remains an open question. And I state this with a calm, professional voice, suitable for academic papers. But its subtlety sneaks by people. So, let me emphasize the point:

The complete hand-waving of “we can just make whole islets from stem cells” flies under the marketing and media radar that garners all the attention. This problem by itself will take, golly, I don’t know. A bit more than five years.

Let me return to being more professional: Producing complete functional islets—with proper architecture, vascular structure, paracrine signaling relationships between alpha, beta, delta, and other cells in the right proportions and spatial organization—is a different problem entirely.

Now, ViaCyte uses pancreatic progenitor cells, which are partially differentiated cells that haven’t yet become mature endocrine cells. The idea is that they mature in vivo (inside the body) into islet tissue after implantation. That’s well and good in theory, but in practice, each of the various cells that reside inside the islets are not within a proper architecture that lets them communicate between each other in a manner that yields glycemic control.

Vertex’s approach — differentiating stem cells into insulin-producing cells before transplantation — achieved A1c <7% and TIR >70% in patients who previously couldn’t control their diabetes at all. That’s genuinely impressive. But compare it to the Edmonton Protocol using actual cadaver islets: A1c 5.8%. Organized islets still outperform manufactured cells, which suggests the architecture problem remains unsolved.

The real problem with islets the architecture problem. Using stem cells to create each of the cells with the islet is getting a messy mix of cell types, not organized functional islets. And people have been working on this for at least 15 years, and will likely continue to.

The islet isn’t a bag of mixed cell types; it’s a microorgan with structure that matters. If you could solve this problem, you could grow a whole new mouse.

But this has nothing to do with the Stanford protocol. The cured mice using donor cells, not because they had any intention of curing diabetes, but to demonstrate a whole different way to address other autoimmune diseases.

What This Study Is Actually About

Judith Shizuru has spent her career making stem cell transplants safer—not specifically for diabetes. Samuel Strober’s foundational work was on kidney transplants and organ acceptance. Lead author Seung Kim directs the Stanford Diabetes Research Center, but the study was partially funded by Breakthrough T1D’s Northern California Center of Excellence, whose mission focuses on T1D specifically.

The press release is explicit about the real target. The researchers “expect that the gentler pre-conditioning approach they developed could make stem cell transplants a viable treatment for autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, and non-cancerous blood conditions like sickle cell anemia, or for transplants of mismatched solid organs.”

T1D is the proof-of-concept vehicle, not the destination.

Why use T1D? That’s not really clear, and it’s beyond the scope of this article to speculate. Suffice to say, NOD mice are very well established models for all sorts of autoimmune research, and there’s a long history of procedures and know-how that can be leveraged.

But the ultimate application of this new and novel approach is actually quite profound, not for T1Ds, but for those with lupus and the other diseases.

In lupus, the immune system attacks multiple organs—kidneys, heart, lungs, joints. In RA, it attacks joint tissue. But those tissues are still there. They’re functional; they’re just under attack. Create the hybrid immune system, as this method might do, and it’ll stop the attack, and the native tissues can heal and function normally again.

T1D is fundamentally different because beta cells don’t regenerate. They’re destroyed, they’re gone. Resetting the immune system stops further destruction, but it doesn’t restore what’s lost. You need both:

Immune reset (which this approach provides)

Islet replacement (that don’t come from donors)

Even if we solved the whole-islet manufacturing problem—that is, growing new islets from stem cells—you might still need to match blood stem cells and islets from the same source to create the necessary chimerism. That’s a different technical challenge entirely, but it’s also an entirely new question that would need to be investigated.

Could mixed chimerism work with islets from one source and blood stem cells from another? No one actually knows, but suffice to say, if we ever get to the point where whole islets could be grown, it’s more likely the case that we’d use the encapsulation techniques described in my first article, because it’s cleaner and easier to avoid having to tinker with the immune system.

Coming full circle, this announcement is the kind of study that generates premature “five more years” optimism in the T1D community, but please, don’t fall for the hype that this is yet another step.

In the meantime, watch your CGM. Go for a walk. The habits that keep you healthy today are the same ones that will matter after any cure arrives.

Thank you for making this so clear for non-medical science people. Please keep up the great work!

Dan, great stuff and thanks for raising these important topics. I’m sure you are aware there is an approach that you didn’t mention that involves hypoimmune cells. To extend your metaphor it would be leaving the police force in place and give the “criminals” (islet cells) an invisibility cloak. This obviates the need for immunosuppressive drugs or encapsulation and avoids the chimerism state you point out.